|

Jamie's

Blog

Wednesday 3rd April 2002

There’s

some great entertainment to be had over at the Wine Lover’s

Discussion Group, one of the net’s busiest locales for wine

discussion. The episode in question begins with an

innocent-looking question

about magnetic wine ageing, which then spawns three further

threads developing the topic. Some of the posts are genuinely

funny. Every now and then, someone new pops up trying to peddle a

device claiming to alter the tannic structure of a wine by means

of magnetic fields. You can understand the appeal of a device that

aims to simulate twenty years’ worth of cellar development with

just a few minutes zapping by a magnetic field. But anyone even

slightly scientifically aware would be extremely skeptical about

these sorts of devices. As one poster says, ‘The claims don't

make sense unless everything we know about chemistry is wrong’.

Another quips, ‘The only difference between this and a scam is

that a scam is pitched in such a way as to be believable’. They

are quite right of course: there really is no way that a magnetic

field like this could alter the chemistry of the wine in any way

that would simulate ageing. Extraordinary claims require

extraordinary proof, and the burden of proof in this case lies

with the one making the bizarre claims. And, of course, there’s

no data to back these claims up with. Yes folks, it is quite

appropriate (and not at all closed-minded) to dismiss magnetic

wine ageing immediately and forcibly. The whole thread was

reignited by the involvement of a wine celebrity. I’ve blogged

before about the fascinating interactions that ensue when a wine

celebrity gets involved in an online discussion, and this is no

exception. In this case, the celebrity in question doesn’t

participate directly, but through private e-mails to one of the

individuals on the board, which are then disclosed. It turns out

that, against their wishes, the wine celebrity’s name was used

as an endorsement by someone selling a magnetic wine ager.

Remarkably, the celebrity in question had taken the magnetic wine

ager seriously enough to test it with a couple of bottles of wine,

in a rather misguided spirit of open-mindedness. You can read the

discussion that ensues here,

here

and here.

Sunday 31st March

On Friday night I broke my first Riedel glass. It’s a sort of

rite of passage. Riedel glasses are de rigueur among wine

nuts, and the first time you break one is a coming-of-age moment.

I must confess, though, that while I’ve always admired the

Riedel portfolio, I’ve never owned a full set, let alone several

sets of these ‘stems’ (as they are known among the

cognoscenti). I own just one Riedel, and it’s the cheapest one

they do – the Overture, at a mere £6.50. But it’s a brilliant

glass, and for the last few years I have been using it as my

standard tasting glass for both reds and whites. The other

all-round-useful glass Riedel make is the vinum Chianti, at £11

or so. This is a versatile stem, slightly larger than the

Overture, and it was one of these that I broke on Friday. Riedel

glasses have very thin rims, and when this one smashed it

completely disintegrated with a high-pitched tinkle. Embarrassing

when it’s someone else’s glassware, but these things happen.

My host wasn’t upset though, and proceeded to open one of the

Jamet 1999 Côte Rôties that he’d purchased en primeur

on the basis of my glowing recommendation. Very generous of him.

Do I still rate it as highly a year on? Probably, yes. It’s

still highly perfumed, but some of the initial sweetness and

prettiness on the nose has given way to more meaty, savoury notes,

with lots of green olive character that’s such a hallmark of

traditional styled Northern Rhône Syrah. The palate is currently

quite challenging, with firm, fine-grained tannins and high

acidity, and there’s the merest whiff of oak. All in all a

brilliant interpretation of Côte Rôtie, but one that could do

with five years to open out fully.

Friday 22nd March

I have a cold. Colds are bad news for those who have to taste

wine professionally. The human olfactory system is a relatively

blunt and frustratingly inconsistent tool at the best of times, so

the deterioration in performance induced by viral infections

effectively puts an end to serious wine tasting. Even if I can

still smell relatively well, I’m reluctant to trust judgements

made with an underperforming nose, so I’ve shelved plans to

attend the big Spanish trade tasting this week, and also a smaller

Languedoc bash put on by a retailer. I wonder what the really

serious wine pros do when they get colds. What would happen if

Robert Parker, on whose palate so many peoples’ livelihoods

depend, were to be struck down with a bout of coughs and sniffles

just before one of his all-important Bordeaux preview tastings?

How would the trade cope without his ratings? It would be a

disaster. When I was researching a recent feature for the wine

trade magazine Harpers,

I spoke to a number of scientists researching taste and smell.

This produced some fascinating insights. More senior readers will

be interested to discover that human olfactory performance drops

off steadily after the age of 40. This is partly thought to be due

to normal ageing processes, but also because of pathology. Putting

that in more straightforward terms, each time you have a cold, it

permanently knackers your ability to smell to some small but

appreciable degree. So by the time you start drawing your pension,

the chances are you will have had multiple colds and the damage

they will have wrought to your olfactory epithelium will be

noticeable. So it’s the same old story: as you get older you

gain experience but you lose performance. The good news is that

there is no noticeable reduction in the sense of taste (i.e. the

relatively limited information that comes from the tongue) with

age.

Thursday 14th March

I’ve been feeling a little sluggish today after an enjoyable

wine dinner last night at the House of Commons, hosted by Decanter

columnist and MP Sîon Simon. Present were four ‘members’ and

two ‘strangers’ (to use the official terminology) -- myself

and Decanter editor Amy Wislocki. Some nice wines, too. Sîon

brought two lovely Rhônes. First, the deep, rich meaty JL Chave

Hermitage 1988. Still deep coloured, tannic and tight, but with

lovely complexity. Hermitage is a patchy appellation, but I’ve

never met a Chave that I didn’t like. Second, the 1998 Côte Rôtie

from Rene Rostaing. Yes, it’s a bit young, but it displayed

plenty of that savoury, meaty, green olive Syrah fruit that makes

this one of my favourite appellations. Rostaing has a bit of a

reputation for overdoing the oak, but not here: this was authentic

enough for me, and I’m a bit of a Northern Rhône

traditionalist. My contribution was a bit more hit and miss. The

1995 Arbois Savagnin from Jacques Puffeney fell into the latter

category: it’s not supposed to be a vin jaune (the Jura’s

answer to fino sherry, matured under a flor of dead yeast), but it

still had that tangy, salty, fino nose, coupled with vicious

acidity. Weird. How I feel about a wine like this depends on my mood. Some days I can sort of persuade myself that I actually

like this sort of oddity; other days I wonder how the winemaker

could have spawned such a vinous Frankenstein. The second Goode

contribution was the 2000 Cotat Sancerre ‘La Grande Côte’.

This is no doubt a worth effort, but it got a bit lost in the

crowd. Or maybe it’s just that there’s a limit to how good

Sauvignon can be. Fortunately I hit the mark with the 1996 Ridge

Geyserville. Predominantly Zinfandel in the classic Ridge style,

this seemed much fuller and richer than another bottle of the same

wine I had a couple of weeks back, which had begun to drop its

fruit a touch. One other scribbled entry in the notebook reveals

that I quite enjoyed the 1990 Gevrey Chambertin from Mortet, which

showed some tasty undergrowth character and quite a bit of chewy

tannic structure. A good evening.

Wednesday 13th March

I’m in the process of pensioning off my old IBM Thinkpad 600

laptop on which wineanorak has lived for the last couple of years.

The new machine is a faster but somewhat flimsier-feeling Dell,

which currently lacks the comfy familiarity I have with my

Thinkpad. I’ve also bitten the bullet and decided to move away

from Outlook Express as my e-mail program, which I've now

officially replaced by Eudora.

Outlook has proved itself to be a serious liability in terms of

security: over the last couple of months I’ve been hit by two

viruses, one of which was particularly nasty and disabled my

antiviral software, making it tricky to clean up. OK, I was stupid

in not doing weekly updates to the virus scanner, but without

Outlook I wouldn’t have been hit by these malicious worms in the

first place. The transition hasn’t proved straightforward, and I

spent most of yesterday evening head-scratching, but I’m almost

done. Laptops are amazing things. It’s like having an extension

of your brain. Clearing out the old machine, I’ve rediscovered

all those old feature ideas, bits of background research and

hastily typed thoughts that without my laptop would have been lost

forever. OK, it’s nothing I couldn’t have done with good old

fashioned pen and paper; it’s just that modern communications

and portable computers have made the whole process so much more

focused, accessible and space-efficient. Just think: with a

laptop, digital camera and access to a telephone line I could

travel the wine world and still publish wineanorak on a daily

basis. Now that would be fun… On a separate issue, I've recently

had my first news piece published on Decanter's

website, on the identification of a fifth taste receptor. And for

those of you who subscribe to the wine trade magazine Harper's,

look out for a 2000 word feature on the science of taste and smell

as it relates to wine tasting, due out in the next couple of weeks

I think. Gripping reading. Other goodies to look forward to

include my first Decanter feature (commissioned but not yet

written) and a short 300 word piece in the G2 section of The

Guardian. It's starting to take off...

Thursday 7th March

As I write I'm sipping a delicious Syrah: it's my third time

with the 2000 Vin de Pays des Collines Rhodaniennes from Domaine

Mouton in the Northern Rhône. Yours for £6.50 from La Vigneronne

-- I bought eight, but should have got more. What more could you

want from a relatively inexpensive red? It's got some of that

distinctive, meaty, green-olive tinged nose typical of a good Côte

Rôtie. Perfumed and very savoury, it's medium bodied with good

acidity. Good with food, but enjoyable on its own, too. You could

spend substantially more and get something less authentic and far

less satisfying. You probably think I'm mad, but I'd prefer this

Mouton to two rather expensive Northern Rhône wines I tried this

week at Bibendum's

en primeur tasting. First, the Hermitage La Sizeranne 2000 from

Chapoutier. It's not a bad wine: medium bodied and quite chunky,

it's reasonably sophisticated, but the spicy oak currently

dominates the nose and the palate. My problem is that a wine from

this exalted appellation should be special; this is distinctly

average. At an en primeur price of £30.74 per bottle, average

just won't do. The second wine is the 2000 Côte Rôtie Cuvée

Classique from Rene Rostaing. A vivid purple colour, this has a

spicy caramel-edged nose. The palate is woody and spicy, with

firm, dusty tannins. It's currently quite wood dominated and

unintegrated, but my main problem is that it doesn't display any

of that wonderful Côte Rôtie character. I'll happily pass at £23

per bottle. Hmmm, pour me another glass of the Mouton.

Monday 4th March

Kew Gardens is an interesting place, even in March. We spent

an interesting half-day there on Saturday, which turned out to be

a brilliantly sunny spring day. Kew has a remarkable collection of

plants, but (as far as I am aware) no Vitis vinifera (grape

vines), alas. However, my browse through the various glass houses

got me thinking about plants in general. I’m fascinated by them.

Is suspect the grape vine would make most peoples' top ten list of

important plants, along with the likes of the olive tree, arabica

coffee, wheat, barley, rice (the world's most important food crop)

and cocoa. People underestimate plants. We tend to think of them

as unremarkable, stationary, background-ish sorts of organisms.

This is wrong. Instead, we should think of them as very clever

environmental computers. The outside world is heterogeneous, and

whereas we monitor and compute the environment and then use this

information to move to where we consider it to be the most

favourable (or fit for our means), as sessile organisms plants use

environmental information to determine their growth form. They can

sense light, gravity, humidity, air quality, fungal attack, insect

predation and even touch, and then compute this information to

alter their growth form and internal chemistry. Some of these

responses are pretty specific: for instance they can release

volatile signal chemicals in response to being munched by a

specific species of caterpillar that then act as an airborne SOS

to recruit the parasitic wasps that prey on this uninvited diner.

Nifty, eh? In part, viticulture is a science built around

manipulating these environmental responses in grape vines. Good

growers seek to encourage the vine to produce the best quality

grapes. It’s somewhat of a black art, as the scientific basis

behind producing great as opposed to merely good grapes is poorly

worked-out. Who understands the science behind terroir? We can

describe geology and climatic conditions, and prescribe pruning

practices and other viticultural interventions, but it’s another

matter to actually link these scientifically with grape

characteristics, let alone the qualities of the final wine.

Sunday 24th February

Spring is on its way in Twickenham. Out in the garden the

daffodils are in bloom, providing violent splurges of yellow amid

the late winter browns and greys. The pear tree leaf buds are

swollen and bursting with latent potential, and the grass seems to

have taken on a fresher, lighter-green hue. I have finished

pruning the still-dormant vines, and in their reduced, lifeless

state it's hard to imagine that they'll be capable of bursting

into vigorous life in just a month or so. Today, though, is still

cold and wet and grey, so we've not yet seen the back of the long

English winter. In a bid to overcome my self-diagnosed bout of SAD

(seasonal affective disorder, suffered by those of us inhabiting

far-northerly latitudes), I've spent the last week in the

Tenerife, the largest of the Canary Islands. Brilliant sunshine

and temperatures in the mid-twenties centigrade are very welcome

at this time of year, and in addition to self-indulgent

beach-bumming we hired a car and explored. Of interest here is the

fact that Tenerife produces a fair amount of wine, and is the

proud possessor of no less than five Spanish DOs. I checked out

some of the vineyards, and they look really weird; unlike anything

I've ever seen before. The knarled old vines, dormant at this time

of year, are trained low along the ground, like wizened, geriatric

snakes. They are frequently supported by forked sticks, just a

foot or so above the barren-looking volcanic soil. As to the

wines, I only tried a couple, so I can't really comment. Instead,

my best wine moment of a non-wine-focused trip was provided by the

sensationally good Torres Fransola 2000. From Penedès, it's

predominantly Sauvignon Blanc, together with a dash of the local

Paralleda grape, and half of the wine was fermented in new

American oak barrels. But don't let this put you off: the oak

merely adds some texture and spicy complexity to what is a

brilliantly full flavoured, aromatic wine -- one of the best

examples of Sauvignon I've experienced. Two other more modest

Torres wines also impressed. The 2001 vintage of Vina Sol (a white

wine made from Parelleda) is a wonderful example of commercial

winemaking. Retailing for around 5 Euros, it is crisp, aromatic

and delightfully poised, with good acidity. It's red sibling, the

Sangre de Toro 2000, is a Grenache/Carignan blend showing an

attractive savouriness along with a good density of fruit. Both of

these cheapies are superb, versatile food wines.

Wednesday 13th Febraury

An interesting tasting yesterday at the Lansdowne Club, put on by

McKinley Vintners. The club's dress code stipulated that

'gentlemen' had to wear jackets and ties: a quick phone call

confirmed that this category included me, so it was the first

trade tasting I've attended wearing a suit. It's actually quite

fiddly tasting with a tie on. You have to make sure that when you

bend over the spittoons (in this case it was those awkward little

table-top efforts -- I much prefer the bigger floor-standing

ones), your tie is not in your spit stream. Very important.

Highlight of the tasting was a vertical of Champagne Gosset. We

were treated to four vintages of Grand Millésime (82, 85, 89,96),

three of Celebris (82, 85, 89), and as a special treat four older

vintages of Gosset Brut (52, 61, 75, 76). All these were

impressive wines, but most fascinating were the four 'old ladies'.

The 1976, from magnum, was fresh and still quite fizzy, tasting

pretty youthful in a complex, high-acid style. 1975 had a gentle

mousse and showed subtle, complex creamy, toasty characters with

just a touch of caramel: lovely balance. Then the 1961, which was

made some years before I was born. This was more evolved, with

some herby complexity and rich, warm flavours. How do you describe

wines like these, let alone rate them? The 1952, from a great

year, was absolutely fascinating. This is a deep yello/gold

colour. Not much fizziness, but a wonderfully complex, herby nose

with creamy, toasty elements and a touch of yeastiness. The palate

is rich and smooth: it's actually hard to pull out any dominant

features, but there are lots of savoury flavours that are all

pulling together to create a harmonious wine. Relatively few

clarets and virtually no Burgundies will be in such good shape

after some 50 years, although I should imagine that the

near-perfect cellaring conditions at Gosset will have contributed

to the graceful ageing of these wines -- after all, Champagne is

notoriously sensitive to poor storage.

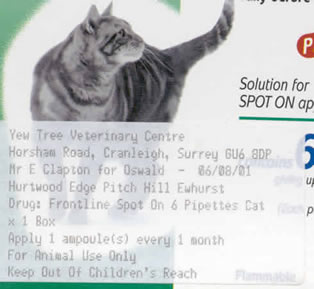

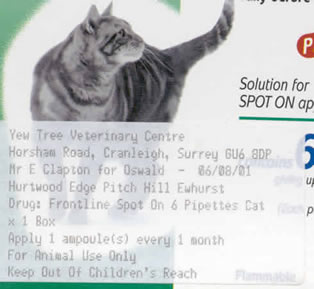

Thursday 7th

February

Forgive

the completely non-wine related nature of this entry, but we have

a new addition to our family. He's a 10-month old black and white

moggy named Oswald. But this is no ordinary feline. Oswald is in

fact a celebrity cat. We feel very honoured by his presence

in our home. His previous owner was none other than Eric Clapton,

the mega-famous, semi-iconic guitarist and rock personality (hard

evidence for this is provided by the picture on the right). But

don't get the impression that Eric doesn't like cats. The story is

that Oswald was hired by Clappo's PA at his country residence and

studio, Hurtwood Edge (a photo of which can be found here)

, to keep the mouse population down. Apparently, when she left for

the USA, there was no one left to look after the poor cat, and

through a friend of a friend he found his way to us. He's settled

in well (I'll post a photo of him soon), but has the annoying

habit of preferring the bathroom sink to his litter tray. Nice. Is

it my imagination, or do his ears prick back attentively when I

play my guitar? Forgive

the completely non-wine related nature of this entry, but we have

a new addition to our family. He's a 10-month old black and white

moggy named Oswald. But this is no ordinary feline. Oswald is in

fact a celebrity cat. We feel very honoured by his presence

in our home. His previous owner was none other than Eric Clapton,

the mega-famous, semi-iconic guitarist and rock personality (hard

evidence for this is provided by the picture on the right). But

don't get the impression that Eric doesn't like cats. The story is

that Oswald was hired by Clappo's PA at his country residence and

studio, Hurtwood Edge (a photo of which can be found here)

, to keep the mouse population down. Apparently, when she left for

the USA, there was no one left to look after the poor cat, and

through a friend of a friend he found his way to us. He's settled

in well (I'll post a photo of him soon), but has the annoying

habit of preferring the bathroom sink to his litter tray. Nice. Is

it my imagination, or do his ears prick back attentively when I

play my guitar?

Tuesday 5th February

A very profitable afternoon spent at the New Zealand trade

tasting, held at regular haunt Chelsea Galleria. This is part of

Chelsea Football Club's Stamford Bridge stadium, which is now

hardly recognizable as a football ground with all the development

that has taken place over the last few years. It seems that

Chelsea FC is an industry, loosely based around a football team.

Diehard Chelsea fans can even live there, should they so wish.

Back to the tasting. You get good trade tastings and bad ones;

this was definitely in the former category. Not too crowded, lots

of interesting wine, and well laid out (a special central series

of tables with wines organized along varietal lines, and

individual producers showing at the tables around the periphery).

It can be quite hard work tasting dozens of Sauvignon Blancs, so I

spent most of my time tasting through the ranges from different

producers. The overall standard of New Zealand wine is admirably

high. The Sauvignons now cover a spectrum of styles, from rich and

rounded to crisp and acidic. Choose which style you prefer.

Chardonnay is now the most planted grape in NZ, but the results

are mixed, at least to this palate. Few are overoaked, but there

are too many examples showing a sort of papaya/tinned peas

character that's a little off-putting. Riesling is crisp and

citrussy, but still trying to find its identity I feel. Does it

age? There are a few interesting Semillons, and some variable

results with Pinot Gris. Gewürztraminer isn't really working that

well, although a few producers have done OK. Of the reds, Cabernet

and Merlot blend quite well, although some overoaked examples

exist. But what really excites me is New Zealand Pinot Noir. I

tasted some 25 different Pinots, and these were uniformly good,

with 10 or so real stand-outs. Special feature to follow.

Sunday 3rd February

There's an excellent letter from UK drinks writer Jim

Budd in the latest edition of Decanter. (March 2002).

Unfortunately, the letters section is not on the Decanter

website, so I'll try to summarize Jim's main points, and

explain why I think what he is proposing is such a good idea. It

concerns the timing of the Bordeaux en primeur tastings,

which take place in the March/April following the vintage. Thus

journalists will soon be tasting the 2001 wines, which are still

in barrel and whose components haven't yet been assembled into the

final wine. For wines destined for long ageing, this is simply too

young. Budd suggests that considering the economic climate and the

high demand (and prices) for the 2000 wines, why not use this

opportunity to delay the 2000 en primeur offer for a year.

Thus Bordeaux would be in step with Burgundy and the Rhône,

regions that are only just offering their 2000 en primeurs

now. This extra year would make a big difference. Critics would be

able to taste the final, assembled wines which, while still

infants, would be easier to assess finally. And customers would

have to wait a year less for their wine once they had paid for it.

Motivated consumers would also be able to taste before they buy,

just as they can now with Burgundy and Rhône cask sample tastings

put on by some merchants. This is a good thing: while critics are

extremely useful, palate preferences differ even among experience

tasters, and these differences in style aren't conveyed by a score

out of 100, which is the currency now used by most merchants in

their en primeur offers. Jim also proposes that "all

the cru classé chateaux should take part in the tastings

organized by the Union des Grand Crus, rather than the first

growths and others with similar pretensions obliging the press and

merchants to visit them. And there should be no separate tastings

arranged for influential journalists." Sensible suggestions,

but is there any chance of these consumer-benefiting changes being

adopted?

Thursday 24th January

My first assessment of the 2000

Burgundy vintage is now up. Over the next few weeks, expect to

see other critics publish theirs. I haven't really tasted enough

wines to give you any definitive conclusion, just 80 or so. In

fact, I wonder how useful verdicts that generalize a whole vintage

are, even if you break down your conclusions along regional lines.

There are just too many variables involved (e.g. when grower chose

to pick, microclimatic variation, viticultural techniques,

winemaking techniques), all of which can affect the quality of the

finished wine. The other source of 'noise' here is the rumour

mill. Critics like to talk to each other and read what the others

are writing. There's a lot of conferring over spitoons, and while

some individuals take pride in ploughing their own furrow, others

are happy to follow in their wake (forgive the mixed metaphors).

So what ends up getting marked down in vintage charts is a highly

subjective opinion, often bolstered by a self-referential form of

vinous Chinese whispers, that is impossible to ground in any

reality. Take the 1996 and 1997 Bordeaux vintages. Most

commentators would agree that the former was a 'better' year. From

my experience, this rings true. But how do you put a number on it?

And for drinking tonight, some of the 1997 wines are a much better

choice than many of the 1996s. What these charts also ignore is

the idea that people differ in their style preferences, and that

the characteristics that cause one person to choose vintage A over

vintage B might cause another person to prefer the latter. Yes,

the vintage chart is a convenient way of trying to help people

through the maze of vintage variations, but it takes so many short

cuts that I'm not sure the eventual result, a number, is any use

at all.

Thursday 17th January

The Burgundy 2000 season is upon us. Suddenly we’re awash

with cask sample tastings and en primeur offers. With the

exercise of all the self-control I could muster, I’ve restricted

myself to just two Burgundy 200 tastings, at Bibendum and John

Armit (reports to follow). Refreshingly, there's so much less hype

surrounding the release of the 2000 Burgundies vintage than there

was with the Bordeaux 2000 circus last March, which was hyped

endlessly. This prompts the question: why are the annual Burgundy

releases relatively low key compared with Bordeaux? A few

suggestions. First, much less Burgundy is made. Even the larger

domaines (I'm not including the big five negociant houses here)

may have just a few hectares of vines, spread over several

different vineyard sites. A classed growth in the Medoc will

typically have 20–40 ha of vines—and there are lots of them.

So there's a lot of top Bordeaux to sell, which means that

merchants stand to make a lot more money from their en primeur

claret offers than from their tiny allocations of domaine-bottled

Burgs. Second, many Bordeaux properties have a substantial

advertising budget—after all, claret is a very image conscious

wine. It therefore makes sound commercial sense for wine magazines

to devote a lot of space to Bordeaux. Yes, Bordeaux is an

important wine region and people are interested in it, but the

commercial reality of Bordeaux advertising money means that

magazine editors aren't worried about overdoing their Bordeaux

coverage. The third reason that the Bordeaux en primeur is

hyped so much is that top claret is an investment medium. Yes,

it's a little bizarre that fermented grape juice should be bought

as an investment, but a lot of en primeur purchases are

made by people who have no intention of drinking the stuff. The

final reason for all the hype is the way in which Bordeaux en

primeur is released. It's sold impossibly early, even before

the final blends are assembled, in the March following the

harvest. All a potential purchaser has to help them decide what to

buy is the opinions of journalists, who have bravely slugged their

way through scores of thick, tannic, mouth numbing cask samples

and tried to give their best impressions. And the wine is released

in batches (or tranches) by the Châteaux, in an attempt to

get the best possible prices from this highly speculative market.

Thankfully, Burgundy is different.

Previous entries (some gripping

reading!)

Back to top |

Forgive

the completely non-wine related nature of this entry, but we have

a new addition to our family. He's a 10-month old black and white

moggy named Oswald. But this is no ordinary feline. Oswald is in

fact a celebrity cat. We feel very honoured by his presence

in our home. His previous owner was none other than Eric Clapton,

the mega-famous, semi-iconic guitarist and rock personality (hard

evidence for this is provided by the picture on the right). But

don't get the impression that Eric doesn't like cats. The story is

that Oswald was hired by Clappo's PA at his country residence and

studio, Hurtwood Edge (a photo of which can be found

Forgive

the completely non-wine related nature of this entry, but we have

a new addition to our family. He's a 10-month old black and white

moggy named Oswald. But this is no ordinary feline. Oswald is in

fact a celebrity cat. We feel very honoured by his presence

in our home. His previous owner was none other than Eric Clapton,

the mega-famous, semi-iconic guitarist and rock personality (hard

evidence for this is provided by the picture on the right). But

don't get the impression that Eric doesn't like cats. The story is

that Oswald was hired by Clappo's PA at his country residence and

studio, Hurtwood Edge (a photo of which can be found