|

Selling pleasure

Jamie Goode charts the incredible success story

of Provence rosé, visiting some key producers

The recent

revival of rose has taken the wine world by surprise.

When I first

started drinking wine, rose was no-go for serious wine drinkers. It

was a small, rather moribund category. But around a decade ago it

started growing, and this growth has been sustained, showing little

sign of dropping off.

Now, this is a

category that I am starting to take seriously. So I was delighted to

be able to travel to Provence, the world's leading region for rose

wines.

Provence seems to

be a wonderful exception in the world of wine. Commentators complain

that the wine sector in general is in poor health. There are falling

sales, over-supply, weak prices and a general lack of innovation.

But against this back-drop Provence is selling more wine than ever,

prices are firm, and it’s a hotbed of marketing experimentation.

But the wines

aren’t serious, nor are they trying to be. ‘We are selling

pleasure,’ says Aurélien Pont, general manager of Château Pigoudet.

And I reckon there are four key elements to the growing success

story of Provence wine: (1) the application of winemaking technology

to improve quality; (2) it's a region with sunshine, sea and a

classy, sexy reputation; (3) a willingness to innovate; and (4)

increased demand across the board for pink wines.

In France, rosé

wine consumption has increased for a couple of decades now, and

since 1990 has tripled overall. Pink wine sales now represent a

remarkable 30% of total wine consumption in France. Globally,

there’s been a 15% increase in rosé wine drinking over the last

decade. In the UK, for example, rosé represented just 2.7% of

supermarket wine sales in 2000; it’s now 11%.

Want some more

facts? Well, here goes. Of all the world’s winegrowing regions, one

can claim to be rosé capital: Provence. Provence has 27 000 hectares

of vineyards spread across three departments (Var, Bouches du Rhône

and Alpes-Maritimes), and makes over 170 million bottles in an

average vintage. The region has 600 wineries, 40 of which are

cooperatives. And, amazingly, Rosé accounts for 88% of overall

production, which is far higher than you’d find in any other wine

region. Altogether, Provence accounts for 6% of the planet’s total

rosé wine production

Most Provence

rosé is drunk in France (84%), with 40% being drunk in the region

itself. After all, it is a wine that superbly adapted to its

environment. Exports are growing, though. They rose 15% in the last

year, and demand from the largest export market, the USA, leaped by

40% over the same period. According to the region’s professional

body CIVP, in the UK year to date figures from May 2014 showed a 60%

increase in sales in volume and 58% in value, which is remarkable.

In particular, one retailer, Majestic Wine Warehouses, has pushed

rosé strongly and accounts for almost 60% of UK sales.

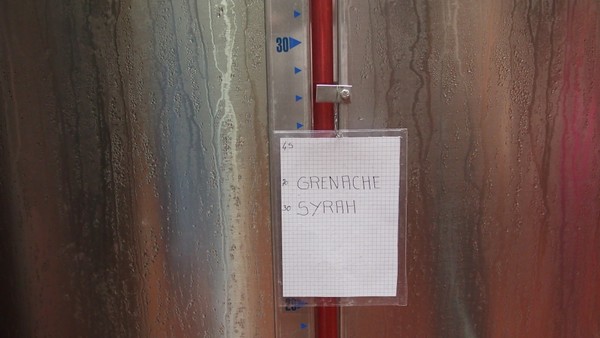

Wine making

technology has certainly helped contribute to the ongoing success of

the region’s wines, because Provence rosé has got a lot better in

recent years. Chief among the advances have been better control of

pressing, protecting the wine from oxygen, and temperature control

during fermentation. ‘The advent of cold fermentation has changed

the taste of Provence rosé,’ says Véronique Goupy of Domaine de

Fontlade. 'We are now able to have much lower levels of sulfites.’

Several wineries are now equipped with the Inertys system for their

presses. It’s a way of keeping all oxygen out of the press by means

of a large ‘lung’ filled with nitrogen, which responds to the stage

of the press cycle by filling the press with nitrogen and then

recycling that nitrogen as the press inflates. This protects the

delicate aromatic components in the juice from oxidation.

Rosé has also got

paler. There is a research institute dedicated solely to the

region’s rosé wines, Centre de Recherche et d’Expérimentation sur le

Vin Rosé, based in Vidauban. Among other things, they have devised a

colour scale for rosé, and are currently researching the effect of

fluorescent lights on rosé wines in clear glass bottles – this is

how most of these wines are marketed. Researcher Nathalie Pouzalgues

explained how important colour is on the perception of rosé wine,

and that their data show that over time, the region’s wines have

gradually got paler. ‘The fashion now here is to have very pale

rosés,’ says Fontlade’s Goupy, ‘But the aroma is in the skin. If you

don’t macerate enough you have no aroma and no colour. It is a very

technical wine.’ So winemakers are walking a tightrope between

getting aromatics in their wines and yet keeping the colour pale.

One way to improve aroma without extended maceration is a process

called stabulation. Aurélien Pont of Château Pigoudet explains how

this works. ‘For the last 6 years we have left the juice on the lees

for 5–15 days before fermentation at low temperatures. This allows

lots of aromatic components to go from the lees to the juice.’ Pont

adds that, ‘If you make a tank just from filtered lees it is very

aromatic and can be used as a blending component.’ Some producers

have also tried more novel techniques (of somewhat dubious legality)

such as leaving Cinsault juice on Sauvignon lees in order to pick up

aromatic precursors.

In terms of

marketing, Provence is proving quite flexible and imaginative.

‘It’s a very dynamic region,’

says Bruno Descamps of Château Gassier. ‘I really appreciate it. I

compare it a bit to Champagne. We are at the high end of rosé wine:

you can bring the fun and the party emotion that we have with

Champagne.’ Gassier are just one of the many producers who are

making super-premium rosé. Theirs, the 946 cuvée, retails for 30

Euros in the region. ‘We see

more domains launching high-end rosés,’ says Liz Comte of Les

Maîtres Vignerons de la Presqu'île de Saint Tropez. ‘That would not

have happened five years ago. Consumer attitudes have changed.’

Possibly most famous of all among the high-end wines is Sacha

Lichine’s Garrus wine, from Château d’Esclans, which is barrel

fermented in a Burgundy style and retails for about the same price

as a Grand Cru Burgundy. It comes from a block of 80 year old vines

from a hilltop vineyard, and was first made in 2006.

Perhaps the most

interesting marketing tactic used by the region’s producers is the

wide array of novel – and sometimes quite unusual – bottle shapes,

something not seen on a regular basis elsewhere in Europe. There are

a number of variations on the classic Provence ‘skittle’ or ‘corset’

bottle, but of late completely new designs have emerged. Château de

Berne are now widely known for their distinctive square bottle.

Thomas Lagarde, wine director at Vignobles de Berne, explains that

four years ago he had problems selling a Viognier wine, until he put

it in a square 50 cl bottle, and then it sold out. So he started

using this bottle across the range, giving customers a choice

between the new bottle and the standard one. ‘80% were buying the

square bottle, so we shifted,’ he says. ‘Sometimes it is a bit more

difficult for wine experts,’ he adds. ‘They tend to reject this

bottle because it is not traditional enough.’ The bottles are made

by Picardy based company Saverglass, and cost 60 c each versus 30 c

for standard bottles. 60% of de Berne’s production is now bottled in

this shape. Château Minuty are another property who have invested in

new bottle designs for part of their range. Their version of the

Provence skittle bottle is popular on export markets and was

designed by the mother of current co-owners, brothers Jean-Etienne

and François Matton. Their elegant new bottle shape, which works

well in the domestic market, was a joint venture: François drew the

label and Jean-Etienne drew the bottle shape.

Pigoudet have

taken the bottle shape one stage further, and now have distinctive,

individual bottle shapes for each of their three top wines, Insolite!,

La Chapelle and Classic. The glass is sourced from Saverglass, and

each bottle costs 40 c for the Chapelle and 75 c for the other two.

Les Maîtres Vignerons de la Presqu'île de Saint Tropez also have a

unique bottle for their top cuvée, the Château de Pampelonne Légende,

which has an unusual flattened profile and is very attractive.

So, the Provence

rosé story is a successful one, in the midst of a European wine

industry that faces some severe challenges. ‘I feel very confident

about rosé sales all around the world,’ says Minuty’s François

Matton. ‘We focus on quality, and we maintain our prices. Production

is the same but demand is increasing.’ There are few regions in the

world of wine who can claim the same.

PROVENCE

ROSÉ:

Introduction Introduction

Jas d'Esclans Jas d'Esclans

Domaine

de Fontlade Domaine

de Fontlade

Mirabeau Mirabeau

Château

Pigoudet Château

Pigoudet

Château

Gassier Château

Gassier

Les

Maîtres Vignerons de la Côtes de Provence Vidaubannaise Les

Maîtres Vignerons de la Côtes de Provence Vidaubannaise

Minuty Minuty

Les

Maîtres Vignerons de la Presqu'île de Saint Tropez Les

Maîtres Vignerons de la Presqu'île de Saint Tropez

Back

to top

|