|

Washington State: introduction

Visiting one of North America's leading wine

growing regions

One of my ambitions as a

wine writer is to visit every wine region at least once. I'm still

some distance from reaching this target, but that's probably a good

thing: after all, it would be an unhappy thing for anyone to achieve

all their ambitions.

This was the first time I'd

visited Washington State, in America's Pacific Northwest, so I was

quite excited. But at the same time, I suspected that I'd make fewer

discoveries here than in its southern neighbour state, Oregon. Why?

Because Washington State is pretty much an entirely irrigated region

–

it's practically a desert. And because it is dominated by one large

wine company, Château Ste Michelle. And because its red wine focus

has been Bordeaux varieties.

In contrast, Oregon is

cooler, has enough rainfall to dry grow vines, is dominated by small

producers, and its main grape is Pinot Noir. But as usual, whenever

I visit somewhere new, I do my best to set any prejudices aside, and

prepare to take on the experience with an open mind.

In the Pacific northwest,

it sits above Oregon and below the Canadian border. Fly into

Seattle, and beyond the city boundaries you are faced with a lush,

green landscape, well watered by the seemingly incessant rain. But

drive inland a couple of hours, heading east over the Cascade

mountains, and it’s as if you have entered another country. Green

gives way to brown and ochre. There’s not enough rainfall to

dry-grow vines, except for in small pockets such as parts of the

Columbia Gorge. But the warm summers and lack of rainfall makes this

a good place for wine grapes, for here there a good supply of water

from the Columbia River, which is the fifth largest in the USA. This

irrigation water has made this an important agricultural region,

known for its hops, cherries, peas and apples. And now wine grapes,

also.

Wine is doing well in

Washington State. The first AVA here was the Yakima Valley,

established as recently as 1983. Then, there were just 40 wineries

here. Now there are 850 licensed wineries in the state (although for

various reasons – such as some wineries having more than one licence

– this number is certainly an over-estimate of the number of ‘real’

wineries, which is closer to 600).

Currently, the wine scene

is growing by just under 9% a year. Vineyard area is now at 57 000

acres (23 000 hectares), which is double the size of Oregon, but it

has the potential to grow to 200 000 acres (81 000 hectares).

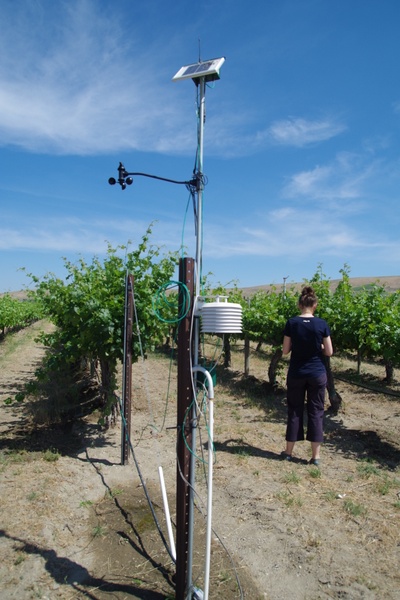

Because of the lack of

rainfall soil organic content is low. The soils are predominantly

sandy, loamy soils over basalt with a thin layer of loess on top

(loess looks a bit like ultra-fine sand: it is fine-grained and made

up of small dust-ike grains). Vines are usually grown own-rooted

here because phylloxera can't cope with the sandy-ish soils. And

there's very little disease pressure because of the lack of rain.

The main hazard here is winter cold, with extreme lows liable to

take out vines from time to time.

The state's reliance on

irrigation does have one advantage, though, because careful control

of irrigation can help with wine quality. In particular, switching

irrigation on and off at the right time can regulate berry size at

the cell division stage, and this is research that has been carried

out at Washington State University. [Berry size is defined at

veraison, and for making red wines smaller berries are better:

first, they have a higher skin to pulp ratio, and second they create

looser bunches which are less susceptible to disease.]

There is a significant

geological event that has helped create the terroir in the Columbia

Valley. 'What happened here 10 000 years ago made this a great wine

region,' says Chris Upchurch of Delille, referring to a series of

dramatic water events known as the Missoula Floods. 'We imported all

our soils from Utah, Idaho and Montana.' These floods occurred

several times, around the end of the last ice age, in cycles of

warming and cooling. Each time, a huge lake, 700 metres deep, was

bounded by glaciers. When these melted and failed, the water was

released, creating a huge wave. ‘In Missoula you can still see on

the hills the layers where the lake was,’ says Upchurch. ‘This was

discovered by a park ranger in the 1920s.' The fact that this great

mass of water couldn’t pass quickly through the Wallula Gap (a

narrow break in the basalt folds along the Columbia river in the

south of the state. pictured below) meant

that it had plenty of time to deposit sediments (slack water

deposits) which now form many of the soils in this part of the

state.

One of the distinctive

features of this large region is the dominance of one large company:

Ste Michelle Wine Estates, which in turn is owned by tobacco company

Altria (previously known as Philip Morris). The most famous name in

the portfolio is Chateau Ste Michelle, closely followed by Columbia

Crest. Other wine brand include Col Solare, North Star, 14 Hands and

Spring Valley. This dominance reflects the history of winegrowing in

the state. The company began as the National Wine Company in 1934,

and this then merged with the Pomelle Wine Company to form the

American Wine Growers in the 1950s. In 1967 famous Californian

winemaker André Tchelitscheff joined as a consultant, and a new

name, Ste Michelle Vintners, was adopted for wines made exclusively

from vinifera varieties. In 1976 the winery moved to Woodinville and

the name changed to Chateau Ste Michelle. The dominance of Ste

Michelle Wine Estates is reflected in the fact that they buy around

two-thirds of Washington State's production of vinifera grapes

(there's still quite a bit of Concord, an American non-vinifera

variety grown here).

Aside from Ste Michelle,

the other notable large winery in the state is the Columbia Winery,

which was first started in 1962 by a group of 10 friends (six of

whom were Washington State University Professors, led by the dean of

the psychology department, Dr Lloyd Woodburn). The winery began in

Woodburn's garage, and was called the Associated Vintners. In 1963

they planted the first vines at Harrison Vineyard, and a big step

was taken in 1979 when they hired David Lake, the first MW in north

America. They were the first to do vineyard designate wines in the

state in 1981, and in 1983 changed their name to Columbia Winery. In

1988 David's inaugural Syrah release was the first example of this

variety from Washington State. Since 2012 they have been owned by

Gallo, and in this short time production has risen from 100 000

cases in to 400 000.

The structure of the

Washington State wine industry reflects the dominance of larger

companies. 90% of wines from the state retail in the USA at $12 or

less. They are mostly well made, tasty wines that deliver good value

for money, but which have very little sense of place. This is where

the Washington State identity problem begins. Some wines are

labelled as just Columbia Valley (the catch-all AVA that covers

about 99% of the vineyards in the state), without mentioning

Washington State on the label at all. But not having the state’s

name on the label has meant that the brand equity in Washington

State has not been built as strongly as it ought to have been.

The first AVA in the state

was the slightly more meaningful Yakima Valley (1983), which remains

the largest of the proper AVAs, closely followed by Horse Heaven

Hills, Red Mountain, Snipes Mountain and Wahluke Slope, which were

all designated in the 2000s. Perhaps the most interesting AVAs for

fine wine are the more easterly AVAs of Columbia Gorge and Walla

Walla, both of which straddle the border with Oregon.

There are five varieties

that have more than 1000 hectares under vine. While Riesling is the

state's most famous white variety, there's actually more Chardonnay

planted here (3100 versus 2600 hectares). Of red varieties, Cabernet

and Merlot are kings (4200 and 3300 hectares respectively), with

Syrah a rising star (1300 hectares).

'Washington is in this

weird state of being able to do a lot of things very well,' says

Marcus Miller of Airfield Estates. 'My personal favourite is

Cabernet Sauvignon, but the grape we do most of is Chardonnay.'

Although Merlot is widely

seen as a junior and lesser partner to Cabernet, here it excels,

making wines with presence and structure. 'Merlot to me is one of

the stars of Washington State,' says Bob Bertheau of Ste Michelle.

Caleb Foster, winemaker for J Bookwalter, is even more bullish about

this grape: 'Merlot here is the best in the world,' he says. 'There

are two great places on the planet for Merlot: Washington State and

Pomerol.'

'In 20 years’ time

Washington State will be known for Syrah,' says Jeff Lindsay-Thorsen,

whose boutique operation WT Vintners is making some stunning wines

from a lock-up in the Woodinville Warehouse district. 'Cabernet

grows well in Washington, but Syrah reflects the place where it is

grown.' Boo Walker of Hedges adds that, 'if Syrah were easier to

sell, we would grow a lot of Syrah.’

Despite the structure of

the industry, with the dominance of more affordable wine, there’s a

growing fine wine dimension here, too. Smaller producers are

increasingly making wines that are catching the attention of

critics, and there’s a welcome move away from the big, riper-styled

red wines that have been popular in the past. This tendency to

favour ripeness has been encouraged by the wine law that allows

significant water addition to must to reduce the potential alcohol

levels. ‘We do some water backs if the sugars get out of control,’

admits Ste Michelle’s Berthau. ‘The regulation is that you can't go

below [water back to] 22 Brix which is ridiculously low. It is very

common here.’ But, he adds, ‘Winemakers and critics together are

moving away from the high alcohol and sweet fruit combination.’

WASHINGTON STATE WINES

Introduction Introduction

Betz Betz

Columbia

Winery Columbia

Winery

De

Lille De

Lille

WT

Vintners WT

Vintners

Savage

Grace Savage

Grace

Chateau

Ste Michelle Chateau

Ste Michelle

Andrew

Will Andrew

Will

Airfield

Estates Airfield

Estates

Hedges Hedges

Milbrandt

Vineyards Milbrandt

Vineyards

Ciel

du Cheval Vineyard Ciel

du Cheval Vineyard

Col

Solare Col

Solare

Powers/Badger

Mountain Powers/Badger

Mountain

J

Bookwalter J

Bookwalter

Pacific

Rim Pacific

Rim

Gordon

Estate Gordon

Estate

Long

Shadows Long

Shadows

Seven

Hills Seven

Hills

Charles

Smith Charles

Smith

Geology

with Kevin Pogue Geology

with Kevin Pogue

Leonetti Leonetti

Woodward

Canyon Woodward

Canyon

Gramercy

Cellars Gramercy

Cellars

L'Ecole

No 41 L'Ecole

No 41

Columbia

Crest Columbia

Crest

Maryhill Maryhill

Memaloose/Idiot's

Grace Memaloose/Idiot's

Grace

COR

Cellars COR

Cellars

Syncline Syncline

Wines

tasted 06/15

Find these wines with wine-searcher.com

Back

to top

|