In Georgia, on the qvevri trail, experiencing the living fossil of wine

Jamie Goode travels east, 8000 years back in time, to visit Georgia and experience wine as it would have been made in antiquity.

Back in 1938, fishermen off the coast of South Africa pulled out a weird-looking fish. It looked quite primitive, and they’d never seen anything like it before. This fish was later identified as a coelacanth, and remarkably zoologists at the time thought this this species had become extinct around 80 million years ago. The coelacanth was a living fossil.

That’s kind of how I felt going into my first Georgian wine cellar. Here, in the part of the world that is considered to be the cradle of wine – where vines were first domesticated some 8000 years ago – I saw wine being made just as it would have in antiquity. The key to this is the qvevri, the unbroken connection with the past, the wine world’s living fossil.

It’s a sunny September day, and we’re in the village of Vardisubani in the Kakheti wine region in eastern Georgia, where we’ve come to meet a fourth-generation qvevri maker, Zaza Kbilashvili. We enter the gates to what seems to be a normal domestic residence, but in the basement of the house, there are several large clay vessels in the process of being built. They are already almost as tall as me, but there’s clearly quite a bit yet to be added to each. It’s quite cramped and dark in the basement, but the smell of damp clay is intoxicating: it takes me back to pottery classes at school: they were some of my favourite lessons. (And if I were to go back now, I know what I’d be making, as big as they’d let me.)

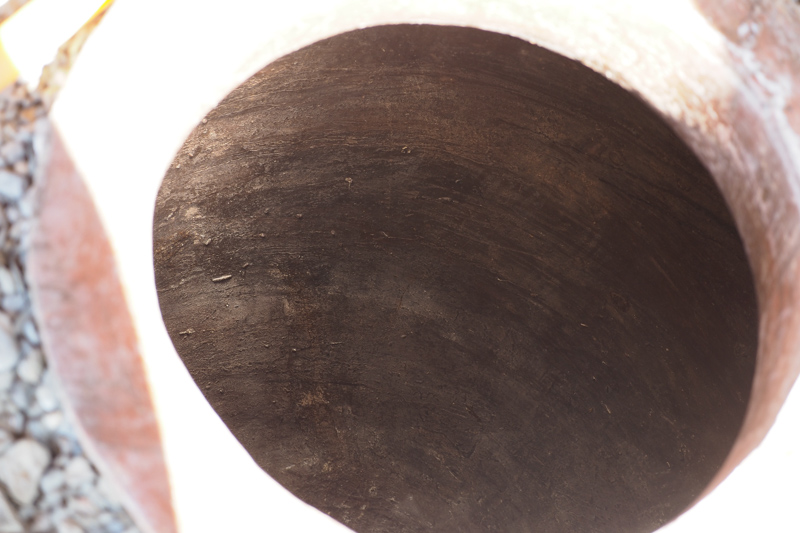

Qvevris (sometimes spelt kvevri) are the traditional vessel for making wine in Georgia, and it’s sort of appropriate that our first stop should be here: they are, to the outside world, the symbol of Georgian wine. But unlike in other countries where terracotta amphora (currently enjoying a renaissance) are free-standing, these qvevri are buried in the earth. When you enter a traditional Georgian wine cellar – a marani – you only see their openings. Marani floors are usually made of bricks, and every now and then there is a brick circle, surrounding the qvevri mouth.

Georgia’s history of wine production goes back 8000 years. This unique way of making wine has survived, partly because this heritage of winemaking has followed an unbroken lineage.

In the past there were many villages that specialized in qvevri manufacture. Now it is restricted to just a few, in three regions: Kakheti, Imereti and Guria. Zaza’s profession was dying out, but with the recent attention that qvevri wines have achieved, his order book is now full. The demand is not just local: there are also plenty of orders from abroad. But should you want to buy one, you will have to wait two years. The cost? Surprisingly affordable, at 2 Georgian Lira per litre, so a 3000 litre version would set you back 6000 Lira (GBP£1620 or US$2100). Zaza says that there are seven or eight families still making qvevri, but I wasn’t sure whether this was just in the Kakheti region, or in Georgia overall. If they are broken, they can’t be repaired, but well maintained they can last for centuries. His facility produces around 50 a year.

Qvevri of different sizes exist. They can be 6000-8000 litres, but most are 2000-3000 litres. The following names are used to refer to qvevri of different sizes:

- Churi

- Dergi

- Lagvini

- Chasavali

- Khalani

- Kotso

One of the big advantages of qvevri is the way that, when they are sunk into the ground, they maintain a fairly steady temperature. The other advantage is that this traditional way of making wine means that, if a good degree of hygiene is maintained, no additives are needed. The qvevri has become a champion of the natural wine movement, although not all qvevri wines are natural wines.

The shape of the qvevri is thought to be important. The bottom is like a pointed cone, and at the end of fermentation, the seeds separate from the skins and fall to the bottom of the vessel. These are then covered by the lees, and are kept away from the wine. So the wine finishes fermentation and ages in contact only with the skins and lees, and doesn’t extract the more bitter seed tannins. The tannins present in the wine bind up any proteins that would otherwise stop the wine from appearing bright and clear, and they clarify naturally in the qvevri. In the past, there is evidence that winemakers used to add crushed flint to the wines to help with removal of tartrates.

Zaza explains how the qvevri are made. The clay comes from the local forest, and after it is cleaned so that it’s free of stones and debris, it’s ready to go. He shows us how they start, with the base. Then, after this, the walls are built up a little at a time: around 20 cm in one go. How often this is possible depends on how long it takes the previous layer to dry enough to put the next one on, which is weather dependent. This construction is all done by hand and eye: no template is used. The maximum capacity he can produce is 3000 litres.

Once the qvevri is finished – and around eight are built at any one time, because this is the capacity of the kiln – it is allowed to dry. Then Zasa enlists friends to help, and these large vessels are carefully taken down to the bottom of the garden to the brick-built kiln. It takes six people to move one. Once they are in place, the door is bricked up, and the long process of firing begins. The fire must reach temperatures of 1200-1300 C. The hotter the fire, the less porous the qvevri. This temperature has to be maintained for several days, so they take shifts monitoring the fire. It’s quite a process.

Waxing

It’s possible to make wine in unlined qvevris, but mostly they are waxed, especially when the pore size is larger due to a lower firing temperature. Usually, the qvevri is waxed before it is put in the ground, although it is possible to do it later when it’s already in the ground.

The qvevri is heated by lighting a fire inside using dried vine cuttings, turning it slowly. Then, once it is hot, the ash is removed. Then melted beeswax is added, and is soaked up by the qvevri walls. The wax is applied by a piece of cloth fixed to the end of a long stick, and it is applied from the bottom up. Buried qvevris can also waxed: in this case an open-topped metal cylinder with a fire burning in it is lowered into the vessel (the chimney has to be long enough to take the smoke out of the qvevri). The important thing is that there’s not too thick a wax layer: the wine needs to be in contact with the clay for the proper qvevri experience.

Liming

The outside of the qvevri is usually coated with lime. Sometimes they are coated with cement, but lime is better because it lasts much longer. Liming improves strength of the qvevri and helps with the winemaking process. Especially when the qvevri is buried in damp soil, lime is much better than cement. The liming is traditionally done with a lime grout that is 1 kg lime to 2 kg of sand, together with rubble and sandstone fragments, and perhaps fragments of old qvevri. Typically, this would be done in situ, as the qvevri are being placed in the ground in the new marani. The thickness of this lime is 10-25 cm.

Washing

Washing is a critical phase. In the past this has been done by lime water, which is sprayed on the inside of the qvevri, and then poured out, to be replaced with boiling water. The lid is replaced and then a while later the softened dried pomace and lees can be removed. To prepare the lime wash, the lime is burned and then dissolved in the water. The water is separated from the precipitated lime and then used to wash the qvevri. The wall is cleaned by a special brush formed from the roots of St John’s Wort, or the bark of cherry trees. Sometimes ash water can be used instead of lime water. To make this, wood ash is boiled (1.5 kg to 3-5 litres of water), and then the wash water is drained off the sediment. Sometimes raw ash can be applied to the inside of the qvevri while the walls are wet, and then dries, protecting the vessel if it is to be left empty for a while.

Sulfur wicks are often burnt inside the qvevri to sterilize them, typically 3 g/100 litres of volume. It’s best if this is done while the walls are still wet.

Lidding

The lid is usually made of wood or stone. The stone lids were very popular in eastern Georgia, and were made from slate from the slopes of the Caucasus. The wooden lids are made from linden, chestnut or oak. The tradition in the east is to use wet clay on the surface of the qvevri neck, and then add the stone lid. In the west, they’d add the wooden lid and then cover this with earth.

Winemaking

In the east, in Kakheti, it was traditional to use all the stems and skins in the ferment. Sometimes the grapes would be crushed a bit first, but the entire skins and stems would be placed in the qvevri. For whites, the skin contact would extend for six months. For reds, it is shorter: just the duration of the fermentation, and then the wine is pressed back to the qvevri. In the west, in Imereti, it was normal just to use around 30% stems. There are lots of variations of winemaking in qvevri, we found, as we visited a range of different marani in the region. The interesting thing is that usually the whites have longer skin maceration than the reds.

We finish our visit with Zaza by drinking some cha cha with him. It’s the local grape spirit: after the wine from the qvevri is removed, the pomace is taken out and distilled. The result is a potent but quite delicious grape brandy: something we’d sample quite a lot of after meals on our trip.

See also:

An article on Georgian wine: visiting Georgia, a country of contrasts

A short film: In Georgia, on the qvevri trail