Can physical AI help us understand smell and taste? Will robots one day be wine geeks?

We’ve got used to the idea of AI, and how it might be useful. But for many, AI is merely about understanding the world through words and pictures used in machine learning. And they are an indirect representation of the world around us.

As humans, we use our own version of machine learning to understand the world around us. We encounter the world through our sensory receptors: sound, smell, sight, taste and touch are detected by a range of receptors, which then create electrical signals. This is the receptor level, and it tells us very little about the world around us.

What our version of machine learning does is to teach the brain how to combine these inputs to create a model of the world around us. We use predictive coding to then refine this model. And there are also some genetically hard-wired elements involved – for example, a baby monkey that has never seen a snake is alarmed by encountering a model of a snake. This is just one example of many.

And we need to add in here interoception: we are able to sense our own body, and its internal state.

By the time we are adults, we are actually pretty good of making sense of the world around us, and perhaps more crucially, we have learned to make sense of the people around us: we can sense their emotional state from a set of quite simple cues, such as a change in facial expression or tone of voice. We understand the nature of objects, and their properties, and we use this object recognition to help us rapidly make sense of everything around us.

Physical AI is in a busy state of development right now. Moving from an abstract understanding of the world gained through analysing text, the idea is to train agents to operate on reality. Doing things in the real world is complex, and this is why it takes human babies so long to develop. Think of a simple task, like picking up a wine glass. We do this without thinking about it, but it requires a lot of understanding and modelling to do successfully. We need to know exactly how much force to apply, and make some quite precise movements. This is usually done outside of conscious control, unless something is wrong with our modelling. The glass might be slightly stuck to the table, and then we become aware of the error message, and refine our model by applying a bit more upward force, but we don’t squeeze the glass harder in case it breaks.

Lots of work will have to be done before we get an Ex Machina-style agent operating very normally in the real world.

But there’s one area that really interests me, and that’s AI agents operating in the chemical senses space. In order to taste wine, we use sight, touch, taste and smell, acting together, the create the sense of flavour.

Could a machine do that? We’ve heard of the electronic nose, which is a set of analysers looking for odorants, but this is nothing like smelling. We don’t operate like measuring devices, giving a readout of the odorants out there. We do a lot more: the receptor level is just the beginning. Instead, we need to do a lot of modelling and processing to produce the perception of flavour.

Smell is a great example of a sense where we have very little understanding of how we put together olfactory input from the olfactory receptors in our noses to create, for example, the smell of coffee or red wine.

Initial attempts are underway, but until we know how the input from olfactory receptor neurons (each of which have one type of around 400 olfactory receptors) is then combined to make a ‘smell’.

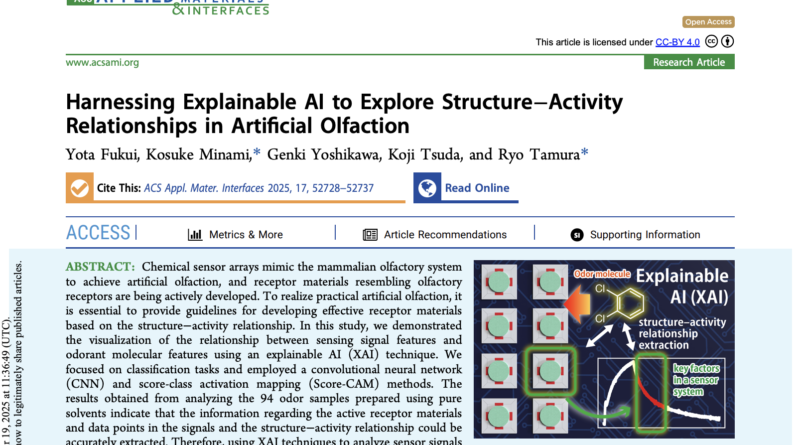

A paper just published has outlined where the current research is. It will be really interesting to follow this field. Perhaps this sort of work is a way for us to finally understand some of the mysteries of olfaction, and with it, flavour perception:

https://phys.org/news/2025-11-ai-reveals-chemical-sensors-odors.html