Lapierre: visiting the natural hero of Beaujolais

This was my second visit to Lapierre, following on from a visit with Camille Lapierre back in 2016. This time both siblings Matthieu and Camille were present, and we tasted through an extensive vertical of the wines they’d made since the passing of their father Marcel.

A quick re-cap. Based in Morgon, Lapierre is one of the most significant domaines in Beaujolais in terms of its impact on the region. The domaine was founded by Camille and Matthieu’s grandfather, who was one of the first to bottle in the area. It was their father Marcel, who died in 2010, who was largely responsible for the reputation Lapierre enjoys today. He took over in 1973, but in 1981 he met Jules Chauvet, the famous wine scientist, who’s widely considered to be the father of the natural wine movement. Chauvet led Lapierre to work in a more natural direction. Lapierre was one of the gang of four, later five, who worked naturally and raised the reputation of the region, making wines that caused the world to sit up and take notice. Villié-Morgon became a hotspot for the natural wine movement in Beaujolais, and with a small band of likeminded winegrowers, Lapierre refined the techniques for working with Gamay without making any additions. Matthieu began working with his father in 2004 after an apprenticeship. Camille joined her brother in 2013.

How do they work? ‘First you need good grapes to make good wine,’ Matthieu says. Gamay is susceptible to botrytis and mildew and sometimes there’s hail, so the grapes need to be sorted. At Lapierre this is done in the vineyard: each picker has two buckets. One is black and one is white. This is because he doesn’t want to leave the grapes on the ground in case the pickers have been a bit too strict. ‘Sometimes I have some plots with botrytis, which is not that fresh and was dried by the sun, but it is too hard to explain to them that this is Ok and the other is not,’ he explains. ‘If there’s too much good quality into the bad bucket, then I can ask them to work with more attention.’

‘We need the grapes to be as perfect as possible to go into the vats,’ says Matthieu, ‘because we do carbonic vinification.’ We go into the winery and see some large wooden vats. I ask whether this is where he does fermentation. ‘The maceration is not really a fermentation,’ says Matthieu. ‘These vats are only used during vinification time to do the carbonic. We fill them with good grapes, but we want the grapes to be fresh. If the weather is to hot we rent some cooling trucks, and it allows us to chill the grapes overnight.’

He puts 3-4 tons of grapes in each vat, and with the weight some grapes are crushed at the bottom. ‘I call it the cooking juice,’ he says, ‘because that is what it is. The juice will provide the carbon dioxide by fermentation with indigenous yeasts, and this is necessary to store the grapes in an air-free atmosphere. We have more or less juice depending on the vintage. If we have too much juice we can take it out, to get the right level. But the best way to control this is the way you put the grapes in.’ If the grapes are more delicate they are put in slowly, so as not to break them. ‘If the vintage gives grapes that are harder, it is better to use a conveyer, so you have enough juice.’ He thinks they need 5-10% juice.

‘The grapes inside the vat don’t ferment at all. What happens is that enzymes inside the fruit start to attack the cells, making the colour move from the skin to the inside of the berry. At this time a lot of acids are being decomposed by the enzymes, some some basal flavour is being created at that time. So without fermentation you will have some aromas and colour extraction, and also some biological transformation of some components into others. This creates some of the base of flavour of the vintage.’

‘We press the grapes after 2, 3 or 4 weeks,’ he says. ‘In 2019 the average was 19 days; not that long.’ By the time the grapes are pressed they are still intact, but are darker and a little bit more red. They are whole cluster still, and so it’s quite a challenge to get them into the press, which resembles a Champagne press because of its shallow cage and wide diameter. This leaves behind the skins, stems and seeds. ‘At the end everything is just flat,’ says Matthieu. ‘The berries are still connected to the stems. We have just extracted the juice, which is red but full of sugar.’ The fermentation starts when they add the free run juice which already has lots of yeast in it. ‘Then, as quickly as possible, we barrel the wine.’ The juice has some properties of wine from the carbonic, but most of the alcoholic fermentation is therefore off the skins.

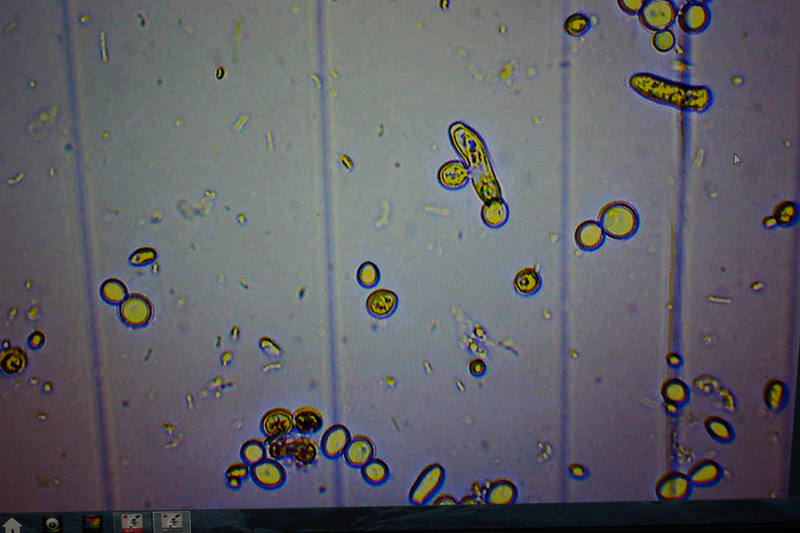

Once fermentation has finished they look at the wine through a microscope to see what’s there. ‘It is always the same question,’ says Matthieu. ‘Do I need to sulfite at the end of fermentation or not? This is the most critical point. The degrees [of alcohol] get higher so the natural yeast has less activity, so they are giving more space to the bacteria. Now have 2 or 3 g of sugar left. If there are not a lot of bacteria we can say we are stable enough.’ If there is too much sugar and they spot the wrong sort of bacteria, sometimes it’s better to do something.’

His father, Marcel, began looking at the fermentations under the microscope, after learning what to look for with the help of a microbiologists. The other natural-leaning Beaujolais producers also tend to do this, and Lapierre shares his microscope and know how (they have a microbiologist who assists to this day) with friends. As I was visiting, Alex Foillard was over checking out one of his ferments.

Matthieu showed me the microscope room. In one wine sample, Matthieu points out that there’s quite a bit of Saccharomyces cerevisiae present, which is good. They are budding, so they are alive and healthy. But there are also quite a lot of bacteria, as single cells, as pairs, and as chains. If these eat up the sugar, then the volatile acidity will rise. And if there’s any brett there, they can have a feed too, with bad results. So what would he do with a wine like this? First of all, he’d try chilling it down to about 14 C, which will allow the yeast to carry on, but which is a bit too cool for the bacteria to cause much trouble. And he would do some battonage, stirring up all the yeasts, alive and dead. If the sugar doesn’t start dropping, then he would consider adding some sulfur dioxide: enough to knock out the bacteria, but not enough to take out the yeasts. ‘It’s a race,’ he says, ‘and the horse that we want to see win is this one,’ pointing at S. cerevisiae on the screen.

Back to the winemaking. Matthieu has 250 barrels and buys five new ones each year. ‘I don’t like new barrels, but I need to replace some. I was not able to find good barrels that had already been used in France last year (2018): because of the nice harvest we had all the cellars are full and there are no barrels to sell.’ The racking is directly from the racking bung of a barrel into a vat. They don’t pump from barrels.

Matthieu likes to emphasize that how they work isn’t just about not using sulfites. It’s about doing a natural ferment. He will use sulfites if he has to and nothing else works. 2015 was a tricky vintage because of the ripeness levels, and there were lots of problems completing the ferments. ‘We didn’t let the brett ferment the wine in 2015,’ he says. ‘We did sterile filtration where there was brett and reintegrated them with barrels that were fermenting with interesting yeast.’

THE WINES

Lapierre Morgon ‘N’ 2018 Beaujolais, France

Supple and smooth. Very elegant with nice red cherries and plums. Red cherries to the fore. Juicy, supple and balanced with nice brightness. 93/100

Lapierre Morgon ‘S’ 2018 Beaujolais, France

Raspberries and cherries. Really supple and elegant with a bit of grip and a grainy mineral edge. Lovely red fruits with some taut cherries. 93/100

Lapierre Raisins Gauloises 2018 Beaujolais, France

They buy in a bit of Morgon for this wine, but it’s mostly from younger plots, and a hectare they have in Beaujolais. The grapes that aren’t good enough for Morgon end up in here. It has 6-7 d carbonic then a fast ferment. Very aromatic and pretty with supple, sappy red fruits and a juicy palate. Fresh and grainy, this is pretty, juicy and smashable. 90/100

Lapierre Julienas ‘S’ 2017 Beaujolais, France

Pepper and ginger notes on the nose with some herby hints. Juicy and expressive with lovely structure. Has some tannin, and a floral, juicy edge. Supple and expressive with lovely weight. 93/100

Lapierre Morgon ‘S’ 2016 Beaujolais, France

Focused, fresh, bright and sappy with nice vivid red cherry and raspberry fruit. Very bright with some grip, and a real sense of precision. Supremely elegant with good structure and focus. 94/100

Lapierre Morgon ‘S’ 2014 Beaujolais, France

This is so supple and elegant, and really fine with a spicy edge. Pure with a bit of stony structure and nice precision. Lovely red cherries and plums with freshness and purpose. 95/100

Lapierre Morgon ‘S’ 2013 Beaujolais, France

Fresh bright and supple with nice red cherry and red currant fruit. Juicy red fruits dominate. Linear with good purity and a nice focus to the fruit. 93/100

Lapierre Morgon 2012 Beaujolais, France

Very precise cherry and plum fruit with good structure. Has a sappy edge to the fruit, and is developing very nicely. 93/100

Lapierre Morgon 2011 Beaujolais, France

This has a lovely density to the sweet red cherries and plums, and shows a nicely sappy edge. Fine-grained structure. Lovely elegance and precision here with good weight, fine spices and real elegance and purity. 95/100

Lapierre Morgon Cuvée Camille 2015 Beaujolais, France

Focused, juicy and bright with red cherries, raspberries and good freshness. Shows lovely purity and precision, despite the warmth of the year. There’s a real harmony to the ripe red fruits, with some grip on the finish. Very fine. 94/100

Find these wines with wine-searcher.com