Interview: Kelby Russell of Red Newt Cellars, a leading producer from the Finger Lakes, New York State

Jamie Goode interviews Kelby Russell, winemaker at Red Newt Cellars in New York’s Finger Lakes wine region, and tastes some of his wines.

Jamie Goode: Finger Lakes is a wine region that has only recently come to the attention of the outside world. Why is this? What is special about the Finger Lakes?

Kelby Russell: The special part is easiest to explain climatically. The real reason for the existence of the Finger Lakes [as a wine region] is actually the Great Lakes. This catches people off guard: we are so used to thinking of the extreme microclimate doing the work, but probably 90% of the climatic lifting is done by Lake Ontario to our north, which we share with our neighbours due west in the Ontario wine regions. Because Lake Ontario is due north and doesn’t really freeze, winter kill isn’t an issue by and large. A really cold wind has to come from the north and it has to pass over a large body of water before it hits us.

The exciting answer about why the wines are so good is that along this narrow strip of land around the Finger Lakes themselves, you have this amazing confluence of slope, sun exposure, and protection from even colder temperatures, giving a long ripening window. Growth is delayed in the spring because the lakes are cold so we avoid frost risk, and then it extends the growing season through late October and early November. For the right grapes, it’s a real chance to make magic, and a real chance to do things aromatically with white grapes in particular that stands out. We have nice diurnal temperature swings and really nice acidity. This is something that has always worked well here. Native grapes come from this area and have been growing here for centuries. There is a reason they grow so well.

The conversion to Vitis vinifera is a much newer thing. It has worked out well.

This is one of the few regions in the world where a lot of wine is made from both vinifera varieties and what we would call hybrids and native grapes. In the wine world we are suddenly beginning to think a little more about non-vinifera varieties, for environmental reasons – they need less spraying. Could you explain the difference between native, hybrid and vinifera varieties, and why are all of these growing in the Finger Lakes?

The natives are the grapes are the grape jelly grapes – that’s the flavour that most people are familiar with. They are grapes that have been here for centuries, and there are crosses of them that we don’t call hybrids. There is a huge stable of them. They tend to be incredibly resistant to disease; they tend to be faster out of budbreak which is now a problem with climate change in the Finger Lakes; they are slip skins – the skins are thick and slip off the pulp of the grape, which is key to their disease resistance, and is also a quirky thing you need to learn to deal with in terms of processing them.

So they are hard to press?

The common treatment is to throw in stems or rice hulls to provide drainage channels. I have seen a press push its doors open through someone not doing enough of that.

The hybrids start with some that have native heritage. There is a real spread. There are hybrids where you wouldn’t know that there are natives in any organoleptic sense – the aromatics don’t lend themselves to the grapey, over-the-top fruity note – it is more about disease resistance or better ripening timelines. The reds are more notable with hybrids, in that they don’t have as much tannin extraction, by an order of magnitude. Hybrids often make red wines that are light and aromatic, and that’s all the rage right now. One of the good things we have seen in Finger Lakes in the last 10 years is the appreciation for lighter-bodied red wines. I think part of the reason Finger Lakes winemakers worked so hard on vinifera for so long is that they were told that this style of wine was of lower quality by some universal metric.

When did vinifera start in the Finger Lakes?

You can find bits and pieces of it being planted in the 1860s. In the 1930s there were some plantings of Riesling and Chardonnay – although not enough for a commercial vineyard. The 1950s is when it really seemed to kick in, with Charles Fournier and the Gold Seal vineyards and Dr Frank. They did amazing work through the 1950s and 1960s, seeing what will work, and coming up with this hilling up and mounding over the graft, to allow them to get through the winter. The real explosion in the Finger Lakes starts in the 1970s with collapse of the grape market that did exist. When [the big companies] stopped buying grapes, farmers were finally allowed to make wine in New York State without having to jump through ridiculous hurdles. We saw a growth in the number of wineries and also the number of more serious vinifera plantings in the 1980s and 1990s. By the 2000s, vinifera is still not the majority, but there was a real push in the marketplace, and this continues to this day. Finger Lakes is a young region, and you find a little bit of everything planted. People will try anything.

Riesling is the variety that the Finger Lakes has become quite famous for. Can you say a bit about it?

It’s a grape that clearly worked from when they were experimenting in the 1950s. I don’t think there is rhyme and reason for what grapes work in a region, other than you know when one does, because it just seems to click into place. This is certainly true of Riesling in the Finger Lakes. You have come through a couple of times and tried the wines: I would say there is an exciting diversity in styles now, which wouldn’t have been true 10 years ago. In the past the idea for Riesling in the region was for it to be very pretty and fruit forward, and finely balanced between acid and sugar. This is admirable, but in the last 10 years we have seen a rush of new styles. At Red Newt this means cold soaking and lees contact and spontaneous ferment. Largely speaking, more emphasis on the weight and structure of the wine than trying to be a pretty fruit-forward expression. For better or worse, we probably have a lot in common with Alsace in terms of our soils: the soil is glacial till, and it changes rapidly between sites and even within sites.

Do you ever have issues with the petrolly TDN aromas in the dry years?

Not in particular. There will be bottlings that have a bit of it, but it isn’t as prevalent as you’d expect.

Can you tell me about your winemaking approach for Riesling? Presumably it’s all hand-picked and whole-bunch pressed?

We actually go the opposite direction. We do an incredible amount of work in the vineyard and then send machines in first thing in the morning. We are looking to cold soak the fruit. I am aware this might not be advisable in 15 or 20 years’ time as we warm up, and the skins get thicker and our acids lower. But at least for now, we chase after this cold-soaked, bigger style of Riesling that requires skin contact. We machine pick, and it’s on the skins for 48 or even 72 h, and then we press off.

You are presumably looking to get flavour components from the skins. But you’ll also get some phenolics. Is that an issue?

This is not a common technique in the Finger Lakes. The initial concern for me was that the phenolics would jump all over the finished wine. If you taste some of the first examples, I left a bit more residual sugar than they needed because of this, thinking that the sugar would help balance them out. If you pick ripe fruit the phenolics will be there but they don’t tend to stick out.

When you press do you protect the juice or let it oxidize?

We do both depending on what lot we are working with. More often we will protect it, especially if we are aiming for a fruitier style. For some others we do brown juice handling. We do pretty standard cold settling in tanks, then rack off. We let it take off on its own. We leave the Riesling on the full yeast lees until the following August or September.

Has the Finger Lakes evolved to the point where people are recognizing which the great vineyards sites are? Within a vineyard region you can have great sites but unless someone is taking those sites seriously, and doing the right sort of viticulture and then interpreting those grapes correctly in the winery, then who is to know whether they are great sites or not? Are people recognising the Grand Cru sites in the Finger Lakes?

It is definitely starting to emerge. The percentage of them that we actually know if is limited by how many of them are planted and how many of them are being farmed so we can work out what makes them special. But there is definitely a dozen or two dozen that are clear stand outs. There is a general understanding of sites that should be better than they currently are. Some of it is also trying to sort out which grapes belong to. For example, there is precious little of Gamay right now. This would be a natural candidate to explore.

Kelby, what was your journey?

I grew up just north of the Finger Lakes on the Eyrie Canal. I graduated from High School and went to Harvard. Maths and science were my forte, and coming from the school I did this was not a likely college for me to get into, so it was a real coup in a lot of ways. I got there and because I’ve always been into music I got into Glee Club. This was like a classical male choir, and I fell in love with that music but I also fell in love with arts management. I thought I was going to become and orchestra manager: this was my career path prior to wine. It vaguely feels appropriate. I feel like managing musicians has a lot in common with managing ferments, in that you have no control over them. I took a summer sabbatical and worked in an estate in the south of Tuscany, Castel de Potentino, and had a fantastic time there. I was just there doing green harvesting. I’d won a fellowship on the somewhat broad brief of going for food and wine. I spread my funds out by exchanging my labour for food and board. I fell in love with wine there, and when I returned I couldn’t shake it. I landed at Fox Run, a long-established winery in the Finger Lakes, and I showed up in a button-down shirt thinking I was going for an interview and was handed a shovel because it was the first day of harvest in 2009. This was when you could work without getting paid in the wine industry. It’s no longer allowed, which is probably for the best – I wouldn’t be in the wine industry if I couldn’t have worked for free in exchange for experience, but I also know that I had the privilege to be able to afford this. Peter Bell, the winemaker there suggested that I should do a harvest in New Zealand. At the time there was no one in the Finger Lakes who had done this. I worked a harvest there and loved it, and the following year I did harvest in Tasmania at Pipers Brook. And then there was one final jaunt to the southern Hemisphere, to Yalumba. They brought me on as the night shift red winemaker for their premium site. This was the opportunity of a lifetime: it was my job to learn what all the winemakers on that team wanted, and manage their ferments the way they wanted overnight. I went from this straight to Red Newt in 2012.

Where are things going with the Finger Lakes?

The big thing in the next five years is going to be the explosion of the Finger Lakes on the US scene. Last summer was the start of it: the visitors that we had that chatter about the wines. There’s no replacing people coming to the region, and loving the wines, and then going back to wherever they are from. The pull through effect is so much more powerful than the push effect. We are going to see that propel the Finger Lakes pretty rapidly. It has been well primed: the wine quality is there, and putting the final pieces together is going to be exciting. From a winemaking side, my hunch is that we will see more Chardonnay, and more thoughtful Chardonnay. It is a grape that has existed here in quite some quantity. The fastest growing thing for us is our red portfolio. The demand is there: people are interested in these lighter-bodied, fresh wines, and it is something that we can do. Within the USA we have a real competitive advantage for this.

THE WINES

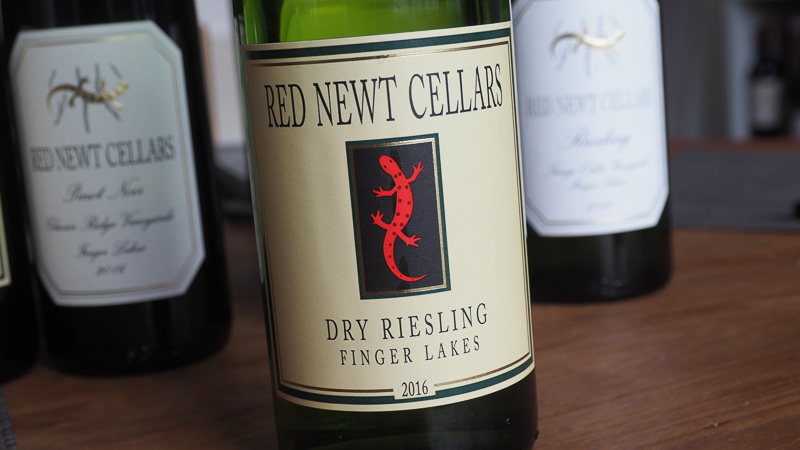

Red Newt Cellars Dry Riesling 2016 Finger Lakes, New York State

13% alcohol. TA 7.1 g/litre, pH 3.15, RS 3 g/litre. A warm year, and unusually dry. This is bright, vital and fruit driven. Lime and lime oil on the nose, leading to a concentrated palate with crystalline citrus fruit, a touch of citrus peel, some honeyed notes and also some crisp green apple. There’s good acidity here. Bone dry and limey, with lots of appeal. 90/100

Red Newt Cellars The Knoll Riesling Lahoma Vineyard 2016 Finger Lakes, New York State

13% alcohol. TA 7.5 g/litre, pH 3.1, RS 5 g/l. This has some lovely texture with bold, refined citrus fruit and some spicy detail. Really concentrated and refined with great precision, showing high lemony acidity really well integrated into the layered citrus fruit on the palate. Superb stuff. 94/100

Red Newt Cellars Tango Oaks Vineyard Riesling 2013 Finger Lakes, New York State

10.5% alcohol. TA 7 g/l, pH 3.15, RS 5 g/l. With a honeyed, baked bread and marmalade nose, this has a little evolution. The palate has a bit of rounded texture with some spicy richness as well as crystalline citrus fruits. Nice complexity here: this is really fine and detailed, and drinking well now. 92/100

Red Newt Cellars Glacier Ridge Vineyard Pinot Noir 2016 Finger Lakes, New York State

13.5% alcohol. This is sweetly fruited and aromatic with a warm herbal edge to the cherry and strawberry fruit, as well as some fine spiciness. There’s some floral lift on the nose, and the palate has a sweet and sour character. It’s a lighter-style Pinot with some appeal. 89/100

Red Newt Cellars Cabernet Franc 2018 Finger Lakes, New York State

12.5% alcohol. Juicy and bright with a bit of grip to the fresh cherry and berry fruits. It’s a lighter-styled red wine with some hints of tar and spice sitting under the juicy fruit. Lovely purity, good varietal character, and nicely light and drinkable. Has a bit of crunch. 89/100

UK agent: The Wine Treasury

Find these wines with wine-searcher.com