Moldova’s best wines, part 1, introduction

Jamie Goode tastes some of the top wines from Moldova, a country where wine is integral to the way of life and the economy.

A brief introduction to Moldovan wine

Moldova lies between 48 and 48 °N in latitude, which puts it in prime territory for wine grape growing. It’s a landlocked country with a continental climate, with an average altitude of 147 m and the highest point 430 m. There’s generally enough rain here (350-600 mm) to dry grow vines, although this is on the low side. Winter lows can be a problem for viticulture, though (they can fall down to –30 °C), so varieties that have cold hardiness are ideal. Generally speaking, though, it’s a pretty ideal place for growing grape vines.

Of all the winegrowing countries in the world, none is so dependent on viticulture as Moldova is. In the 1980s, at the peak of the country’s production as part of the USSR, there were 225 000 hectares of vines making a quarter of the USSR’s wine production. But when Gorbachev introduced controls on alcohol in 1985, some 75 000 hectares were grubbed up.

In 1991, Moldova became independent. By the early noughties, wine was the country’s biggest export earner, with over 90% of production exported. A quarter of the population was connected with wine. But Russia was taking 80% of these exports, mainly with cheap semi-sweet wines. But then in 2006 Russia banned the import of Moldovan wine, with devastating consequences. But this turned out to be a blessing in disguise for the future of Moldovan wine. The wines exported to Russia were largely unsaleable elsewhere, and the failure of this market was a sufficient jolt to make the wine industry consider what it would have to do to sell in more demanding marketplaces.

But a second ban came from Russia in 2013, just in advance of a free trade agreement that Moldova was to sign with the EU. By this time, though, many wineries had reoriented to other markets, and so the ban had less impact.

There are three main regions. In the centre there’s Codru, then in the southeast Stefan Voda, and then in the south there’s Valul Lui Traian.

Moldova’s grape varieties

Moldovan wineries typically use a mix of local and international varieties, and some of the most effective wines are blends of both. Moldova shares quite a few varieties with Romania. Around 70% of the vineyards are planted with international varieties, 30% with Caucasian (Saperavi, Rkatsiteli) and local varieties (Rară Neagră, Fetească Neagră, Fetească Albă, Fetească Regală).

The leading plantings (in order) are:

- Merlot

- Cabernet Sauvignon

- Chardonnay

- Sauvignon Blanc

- Muscat Ottonel

- Pinot Gris

- Pinot Blanc

- Aligoté

- Pinot Noir

- Riesling

- Saperavi

- Rară Neagră

- Fetească Neagră

- Fetească Albă

- Fetească Regală

Some of Moldova’s local (or shared with neighbour) grape varieties you might not know much about:

Viorica

A terpenic white variety, Viorica is one of the most important white grapes in Moldova, and it’s actually a hybrid – a cross between Seibel 13666 (a red-skinned non-vinifera variety, one of the many produced by Albert Seibel) and Aleatico, created in 1969. It shows good cold-hardiness. It’s a terpenic variety, with some similarities in flavour to Muscat and Torrontes.

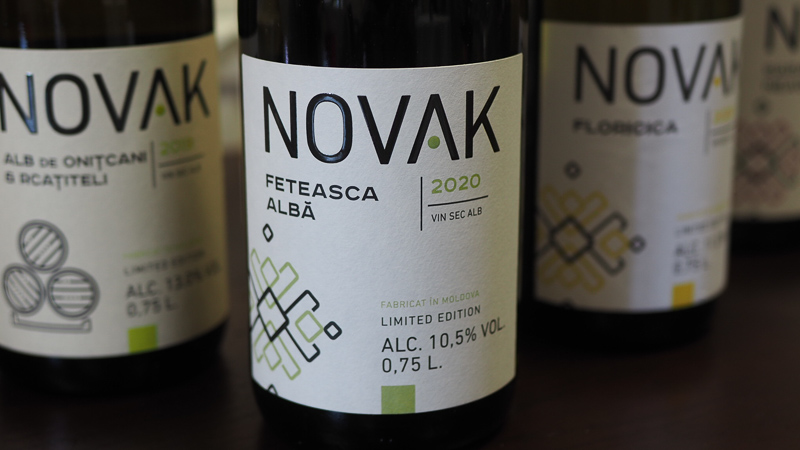

Fetească Albă

This is another terpenic white variety, making some nice fruit-driven whites.

Fetească Regală

This comes from Transylvania in Romania, and it is a crossing of Francuse and Fetească Albă made in the 1930s. It’s a terpenic white variety that often gives a bit more flavour than its Fetească Albă parent.

Fetească Neagră

A red variety that originated in Moldova, but which almost disappeared in this country (although it was widely planted in Romania). It’s attracting increasing attention. It is cold tolerant, and late ripening, and makes wines that are nicely fruity with good colour, and not too much tannin.

Rară Neagră

Known as Băbească Neagră in Romaniam, where it’s the second-most widely planted variety. It’s a really promising variety, and another which had almost disappeared from the country, only to be on the rebound because of its potential. It’s cold tolerant, and makes fruity reds with real personality and good acidity. An old variety with a lot of clonal variation.

Saperavi

This Georgian variety is popular across many of the wine-producing countries that were previously part of the Soviet Union. It’s a teinturier (with red flesh as well as skins), and works well both as a stand-alone variety and a component in blends. Makes deeply coloured, intense reds.

The wines in this report

The 178 wines here represent a selection of some of the best wines from Moldova. The fact that they are pre-selected explains why few of the wines got very low scores. No doubt there are bad wines being made in Moldova – this is the case in all wine producing countries – it’s just that I didn’t get to taste them. Overall, though, I was really impressed by the average quality. A lot of hard work has clearly gone on in the country’s wine sector to improve quality. It shows. Of course, it is entirely possible that some very good Moldovan wines didn’t make it through to this selection, but this is something I can’t comment on. I can’t talk about wines I didn’t taste.

Criticisms? One is that too many of the bottles are just too heavy. I realize that some markets equate bottle weight with wine quality, but the current trend in the wider world of wine is to move away from heavy bottles because of their environmental impact. In some markets, a heavy bottle will disqualify a wine from a listing. This time is not far off in the UK.

The second is that for red wines, many are being picked just a little too late, so the fruit spectrum is heading into the jammy, over-ripe zone. It’s nice to have ripe fruit, but there comes a point where a wine is over-ripe, and loses definition and focus, and gains alcohol.

The third is for an over-use of new oak character. This can be impressive to some, but the current global trend in fine wine is for more balanced wines, without obvious oak intruding on the nose or palate of the wine. Many of the red wines I tasted would probably have been a bit better picked earlier, and matured in older oak, or larger format oak, or even in vessels made of concrete or another neutral material.

Overall, though, this was an impressive set of wines. [Declaration of interest: I was paid a fee by the Wines of Moldova to taste these wines.]

A note on scoring

I’ve scored these wines out of 100, as is common in modern wine criticism. This is an imperfect system, and it gets very congested in the 88-94 point zone into which many decent wines fall these days. But it is the system most widely used. The scores give you a chance to see how much I liked each wine relative to the others, and they are absolute scores. This is an important point: I do not factor value for money into my scoring, and if a Moldovan wine scores 92, it should be the qualitative equivalent of a 92 point wine from anywhere. On this scale anything below 80 is poor and not really worth drinking. A cheap but drinkable supermarket wine might score 81-84. 85-89 is bronze medal territory and a wine that is 88 or 89 points is really nice. 90 points or above is quite fine, with a wine scoring 93 or 94 being world class and quite thrilling. 95 points or above is stunning!