The Business of English Wine (3): making it and selling it

In the third of our series on English wine, Lisse Garnett speaks to three contrasting wine producers about this year’s harvest horribilis, post Brexit pitfalls, still wines and sales

Ruth and Charles Simpson farm 90 acres of prime chalk on the North Downs and are seasoned pros with a successful Chateau in the Languedoc where they’ve been producing wines for firms like Waitrose and Majestic for over 15 years. In 2016 they harvested their first UK crop and today they make 60% still wines and 40% sparkling with fruit sourced entirely from their own Kentish vineyards.

Will Davenport has been growing grapes and making wine on the Kent and East Sussex borders since 1991. In 2000, he converted his 24 acres to organics, and farms 40 more of non-organic that his mother owns. He also makes wines for other growers. Half of his wines are marketed to the on-trade through Les Caves de Pyrene, while the remainder is sold directly via the cellar door and online.

Jose Quintana was born into farming stock in East Sussex, trained at Plumpton, and has worked for Will Davenport, at Westwell, for his cousin out in Spain at Fedellos do Couto in Ribeira Sacra and Bodega Comando G. Two months ago he took over the reins at Vagabond, the urban winery next door to Battersea Power Station on the banks of the River Thames. Vagabond have eight wine bars/restaurants in London, one in Birmingham, with more expansion planned. Fruit is sourced from Oxfordshire, Crouch Valley in Essex and East Sussex and the wines are made in central London. These wines are exclusive to Vagabond customers and are not marketed elsewhere.

Lisse Garnett (LG): What brought you to wine?

Charles Simpson (CS): We sold a nice Kensington flat and bought a 46 hectare estate, Domaine de Sainte Rose in the Languedoc with a 16th century chateau and winery with the proceeds. I was in pharma and Ruth was working in humanitarian aid, we were living in Baku when we decided that we wanted to work in wine. Ruth took up a distance learning course out of the University of South Australia and they sent books via Moscow. She would study while I was busy opening new markets. That’s finally what took us to the Languedoc: we had no desire to make wine in France but just fell in love with the area.

Will Davenport (WD): After university I had no clue what I wanted to do, but I’d found student work in the London wine trade while at University (and I had worked in Alsace in my gap year), so I used my contacts and got a job in a winery in California for 6 months, just to buy some time before I had to get a proper job. When I came back to the UK I worked with Robert Joseph at Wine Magazine for a while and then got a job with David Gleave and Nick Belfrage in London for 2 years as a wine retail manager. Wine retail was not a long-term thing for me, so I went to Australia and studied winemaking and worked for a winery near Barossa Valley. I then made wine for a winery in Hampshire for a couple of years before starting my own vineyard. I never decided to be a winemaker – it just turned out that way.

Jose Quintana (JQ): My cousin’s family made wine, they have grown up with it and I was fortunate to be connected and inspired by them. You can’t transfer that knowledge but you can take the philosophy. I was a working as a sound engineer but I grew up on an arable farm. A chance encounter with a bottle of Chateau Musar re-ignited my love of wine, transposing the desire for volume alone. When the English wine industry gathered momentum I decided to take Viticulture and Oenology at Plumpton College. With three children it wasn’t easy but here I am and I couldn’t be happier.

LG: How was this year’s harvest for you?

WD: This year has been really really tough. It has been one of the most difficult years we’ve had because it rained a lot. If you think back over the summer you may remember some really nice sunny days, but there were also a lot of massive rainfall events that caused big problems with mildew. We’ve had to spend probably 50 percent more time in the vineyard cleaning everything up, keeping everything tidy, taking leaves off, so it’s been quite hard work this year. We’ve had a smaller crop than normal so as usual those years when things are the toughest and you put the most work in, you get the smallest crop. But the wines are nice.

It was a difficult year for everyone but if you talk to other organic vineyards we are actually much better off than everyone else. We picked 23 tonnes which is about ten tons less than normal. That equates to a ton and a half an acre, but is that commercially viable? I’m not sure. I think we will just about break even or thereabouts.

The grapes weren’t as ripe as we’ve have been used to over the last four years or so, because we’ve had some really very good years. So there’s higher acid and lower sugars but the flavours are all fantastic so we are going to make some lighter styles of wine with lower alcohol, in a crisper dryer style – we are not making our Pet Nat this year because it’s too acidic and we are probably not going to make quite as much red wine as we normally make because of the acids again. We are making red wines in a much lighter style – a lot of people have said to me that they like that style of wine. Light pinot Noir, not much colour to it but really nice flavours at 10.5%.

CS: The UK yields are much lower than we ever thought they’d be and so inconsistent – every year there has been a different something – it’s been frost, mildew, poor flowering. We thought that with 30 hectares we could consistently crush about 200, 250 tonnes but not a chance – 8 tonnes/hectare is the average if you look across the UK – it means sometimes you’ll get 12 but often you’ll get three. I don’t know if you saw that Wine GB have just announced that you can chaptalize not by 3 percent but 3.5, but everyone’s just finished!

When we bought here we plotted the UK weather for the past ten years. We thought we had bought frost free vineyards – but we’ve had a frost every single year. We didn’t understand how warm we are here in Kent, so we are budding earlier, we are exposed earlier, we thought we were going to get budbreak in May and we are getting it in early April. The frost comes on the same days every year, its somewhere between the 18th and the 25th of April. It is like clockwork – like flicking a switch.

JQ: We buy all of our fruit and we are not under contract with any growers. We have verbal agreements that Gavin Monery, my predecessor, put in place. We buy from Ed Mitcham at Yew Tree Vineyard, Dale Symons at Clay Hill and David McNally of Hidden Spring.

There was an opportunity this year to hike the price of grapes up because of the shortage. It was definitely a growers’ market, but the people that we work with weren’t thinking like that – they were much more enthusiastic about a long term relationship with us.

There is volatility in a new industry that creates ebb and flow, and anyone who tries to cash in on the short term might find it comes back to bite them. Rather than put the price up and sell to the highest bidder our growers have shared their crop around. We have all had to compromise on volume.

It’s about building trustworthy relationships with growers we like and who have similar philosophies. As we grow we hope they grow with us. We would also like to find new growers, using contacts I’ve made at Plumpton.

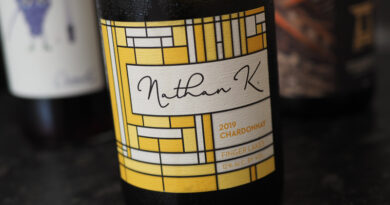

The quality has to be there for still and this year the Chardonnay and Pinot from Crouch Valley were not quite there so we will make more of our Pet Not, an undisgorged frizzante style wine based on the Col Fondo method.

LG: Give us your take on English still wine.

Ruth Simpson (RS): We had promised ourselves that we were not going to make still wine in this country because everything we tasted was so acidic but then we tasted that first harvest in 2016 we kept the Chardonnay 548 separate. We were so enamoured by the varietal honesty, we thought oh my gosh if that was just a couple of degrees warmer potential alcohol that would be a Chablis so that’s what encouraged us to try in again in 17 and pick it riper and then obviously in 18 (a warm year) we were able to do this properly. It’s very fortunate that we made the decision to plant some Burgundian Chardonnay and Pinot that was suitable for still. So we went from thinking you can make still wines once in every ten years to thinking that with certain parcels using certain clones that are being farmed accordingly, there is no reason why we can’t make world class still wines every year.

WD: Our still wine is different to what all the other vineyards are doing because most vineyards are using Pinot Gris, Chardonnay and Pinot Noir and we are still making Bacchus, Ortega and other aromatic Germanic varieties. We are not quite unique – our wine is in a sort of Alsace style. I’m really into Huxelrebe at the moment but no one else seems to grow it. It’s very easy to manage because it’s very vigorous and produces enormous bunches of grapes that are quick to pick. You’ll get 3 tonnes an acre off it even in a year like this and 5 tonnes in a good year. The wine is similar to Ortega in flavour but when it ages you get a slight Muscat air to the wines. It’s very susceptible to botrytis and have made a couple of sweet wines out of it that have been very interesting. We are trying to get a bit more imaginative about what we do with our grapes: we want to keep our customers interested and not keep plugging the same two or three wines.

JQ: Gavin did about six wines here and what I am trying to do is use my remaining vintages, I’m forty odd, to make still wines principally because the iterative process is so much quicker and therefore you can build knowledge. I’m impatient and I want to learn. There is a bit of a niche in England for still, we have a lot of sparkling.

It’s very exciting because Stephen Finch the owner here is willing for me to experiment with the full knowledge that some of the stuff we try here is probably not going to work! If you are not doing stuff that doesn’t work then you are not finding out where the boundary is. We have got to make money; business is business and that’s a fact but if I have to follow a recipe I’m out.

Gavin left a barrel of 2018 Ortega, still on skins, we may release that as a single cuvée or we may try to create a solera system of Ortega here. That’s wonderful because I worked with Ortega a lot at Westwell and Adrian Pike (Westwell owner) and I were always quite enthusiastic about Ortega’s ageing potential. It’s got its grand parentage in Riesling and Gewürztraminer and seems to have the structure and baseline to build complexity. A non-vintage aged Ortega that shows the complexity of what English still wines can do would be a great legacy for Gavin who started it. I want to take it on and see where it goes.

We are doing some skin contact Bacchus, experimenting with lees, moving towards minerality and away from thiols and florals. We love texture here.

LG: Have you struggled with sourcing labour?

WD: We’ve been fine. There are seven of us now at the vineyard and lots of people walk their dogs near our vines at Horsmonden so we put up a sign saying do you want to come grape picking? We had twelve people sign up and it’s been a really good crew. We have our harvest lunch today.

LG: But don’t you struggle with untrained hands?

WD: It works for us because we are very hands on and we are out picking with them. We don’t just leave them to get on with it: I’ve been out picking nearly every day and Philip’s out every day. There lots of us to walk around making sure they know what they are doing and yes you’ve got to accept that one or two of them are not as fast as everybody else, but that’s fine, the main things is that everybody has a good time.

People are charging ridiculous amounts for foreign labour. They are up to £15.50 an hour for picking and then they are turning around and saying well we haven’t got enough people so they can’t do it all at the last minute. I know farms who were booked in for 20 pickers a month ahead and the last minute they say well we’ve only got 12 people for you.

There is a guy from Biddenden vineyards whose got a picking machine and I think he’s been doing very well. I think a lot of people – even the sparkling wine producers – might go down that route because it’s so much easier. You can pick 50 tonnes a day with two people. I don’t know what he charges but it makes a lot of sense I think.

CS: We’ve got a couple of people who live in the village who want a bit of flexible work so we have them on a zero hours contract. They do a bit of pruning, hand harvesting, labelling. Labour is increasingly an issue, even for simple jobs like lifting the wires. Our local agency Proforce was favouring people like Nyetimber who have sites in Kent now, so a lot of the larger producers were sucking up all the labour because they could guarantee it for more days at a time and a small producer like us who needed 20 people for five days – well they are going to Nyetimber for 3 weeks so….it’s been a challenge all year and I don’t think it’s going to change anytime soon. It also affected harvest interns for the winery – we don’t have the antipodeans because they can’t travel yet, and you don’t have the Europeans because you can’t get a work visa for them, and when we went to Proforce and said would you sponsor a couple of interns because we have a couple of French candidates interested in coming to do the vintage and they were just like no we don’t have the numbers. We are not going to go out and get a gangmaster’s license, it’s just a ridiculous amount of paperwork and administration. I think it’s a big challenge for the industry and one that needs to be addressed. The government loves to use English wine as such a success story but they are not making it very easy at the moment.

We can’t use local labour because they don’t have the skills and they don’t have the basic knowledge so it’s time consuming and they don’t want to work all day. Then they want to have lunch.

We hand harvest for the Sparking but we rent this machine harvester from one of the sons at Biddenden for the still – machine harvesting adds value from the still wines perspective because you want phenolics, you want solids in the resulting wines.

JQ: It’s just me: we don’t have any other employees here. I have some help from Vagabond staff on processing days so there isn’t a bit that I am not involved it – it is exhausting but it’s also exhilarating. I am learning so much, not least about the winery which is a beast in itself. There is a real career opportunity for the team here to build up their wine knowledge, you don’t have to know about wine to start here, passion is more important, you can undertake WSET through Vagabond and try hundreds of wines thanks to the reasonably high stock turnover, there are constant tasting opportunities and you can even experience work here in the winery.

LG: Have you struggled with getting any materials or transport since Brexit?

WD: Not really – it’s all about the timing. The timing has been odd: we ran out of silly things like Champagne foils, and I looked up in my record and I saw I had ordered them two and a half months ago, how are they not here yet? But they do turn up: we just have to order everything much earlier. We’ve gotten used to it now. We ordered all of our bottles way up front and then of course there was no problem. We just worked out that things that come from Europe like corks have to be ordered 3 months ahead. We then cross our fingers to hope they arrive.

The next worry is that we are going to see a big price hike on things like glass. We have already warned all of our trade customers that we may have a price hike next year, potentially 20p on the price of a bottle. Most of them seem ok with it. It’s really about just being prepared in advance. We had big increases in cardboard prices this year and delivery costs, all the couriers are chucking their prices up which is totally understandable.

CS: We use mobile bottling lines from France because of the synergies between our two businesses and more than ever it’s been an absolute nightmare trying to get glass – and don’t forget these are relationships we have had for twenty years, these are our friends – they are not suppliers and they are saying, we will gladly sell to you but we are not sending anything to the UK, we just don’t want the customs battles. So another synergy of Domaine de Sainte Rose is that we are now using it as a depo – we are ordering stuff for England and having it all shipped to St Rose, consolidating everything we need and then getting it a full lorry load – because you can get a full lorry load! Try and get a couple of palettes over here? Forget about it… but if you commission a lorry just to do one trip to here from St Rose you can do it so we will fill it…we use the second-hand barrels from the Languedoc for our UK operation too.

JQ: Transport has been a bloody nightmare. The logistics of getting grapes into the winery has been exacerbated by a triptych of problems: drivers, the fuel crisis and the difficult growing year. The difficult growing year meant that you were being forced to make picking decisions very quickly. Ideally you would give yourself a week – I’ve had to hire Luton vans and pick up fruit from Essex and Oxford because you can’t wait around, the job needs doing immediately. The fruit has got to be picked when its ready if you want quality fruit. Our growers are extremely diligent. The best wines can only be made with the best fruit so you simply have to find an answer.

LG: How easy is it to sell English wine?

CS: We sell to Waitrose from both the French estate and the English estate. You go into the French wine buyers room where the key question is ‘How much is it?’… In the English room it’s ‘How much can you give me?’

It’s a dream come true because we’ve been on the other end. It’s so tough to sell Languedoc wines.

We knew there would be high demand for English but we didn’t know we could sell what we make ten times over. We have chosen not to launch in certain markets because we just don’t have the volume. These are markets that we had never expected to be so interested, countries like Norway would take all of it if they possibly could. They get it, they understand cool climate wines and they appreciate the quality and they are not afraid to pay for it. They actually think it’s really good value.

RS: 2016 was our first harvest and we picked some 548 clone (for sparkling) and as it was going through primary fermentation, it was just so interesting we thought let’s do a little still. So 600 bottles of still Chardonnay were produced. That was the very first Roman Road Chardonnay we made. We had so few to sell but we allocated some to the shop here in the village. We had no idea if people would buy it, at that point it was a £23 bottle of wine. We sent a saleswoman down to the shop thinking she was just going to pour a few bottles for everyone to taste and there was a queue outside the door, so she had to come back for more! Everyone wanted a bottle of wine with Barham, the village where we are, on the label.

WD: We made a sparkling wine out of Auxerrois that was nowhere near as good in terms of quality as our Sparkling wine but everyone wanted to buy it. They want to try a different grape variety that they haven’t had before. It’s nice because people trust our winemaking, they think we make decent wine so they give new things a try and will even buy a case on spec.

We sell about 30% of our wines via our own website online, which has probably doubled in the last two years. The customers are all over the UK. We’ve been doing that for about 20 years but when the pandemic started obviously all the restaurants shut and I was a bit worried that our sales would take a huge dive. So we started to become a little more focused on website sales, sending out the odd mailing. Everyone has been locked up at home and they’ve got some spare cash so they say right let’s get a case of wine in. And this year when the restaurants re-opened it just went completely bonkers. We were selling online and sending pallets out to restaurants as well. I think our last two years have been the best ever. It’s a bit odd!

Les Caves de Pyrene, who are our biggest customer: their sales have gone up by fifty percent. And probably about half of what we make goes out through them. The remaining twenty percent is small independent wine shops and restaurants around Sussex. We do a few further away to customers who have been buying direct from us for decades so we’ve carried on selling direct to them.

We don’t do any marketing, it’s just word of mouth really. I’m worried now with our sales going through the roof that we are going to run out of wine in a year’s time, but who knows? We normally produce about 30k bottles a year but this year it’s going to be more like 20k. All of our wine is allocated to trade customers so we tell Les Caves how much they can have and they allocate accordingly.

LG: Will, are you still making wines for other people?

WD: A little bit yes though this year is a bit of a no show as nobodies got any grapes! We’ve got six organic vineyards who bring grapes to us for winemaking and only two of them brought anything in.

JQ: We have a solid route to market as we sell direct to our customers but I don’t think there is that much awareness of the winery here at Vagabond. As we expand I would ideally like to build awareness and build towards some on-trade and wholesale sales. The wines are sold by sample, glass and bottle, you can buy retail and take away the wines. That model is tried and tested and works really well. The wines we make are the only English wines we sell at Vagabond.

We have such a range of customers and every site is different. The city branch will stock different wines to us here in Battersea. What we try and do with the whole spread of wines is to provide variety. We will discover how experimental people want to be when we release our 2021 wines. We want to push the boundaries; both Stephen and I are excited by the unexplored realms of English wines. We have access to fruit that is high in acid, that makes them more stable and you can work with lower intervention. As a young industry we have now gone beyond transplanting methods from other countries and are now creating our own philosophies. English wine is not confined by historic region, we have the varietal scheme that allows us to more open. We have yet to work out what is a quality area so are not yet confined by PDOs. It’s very very exciting.

See also: