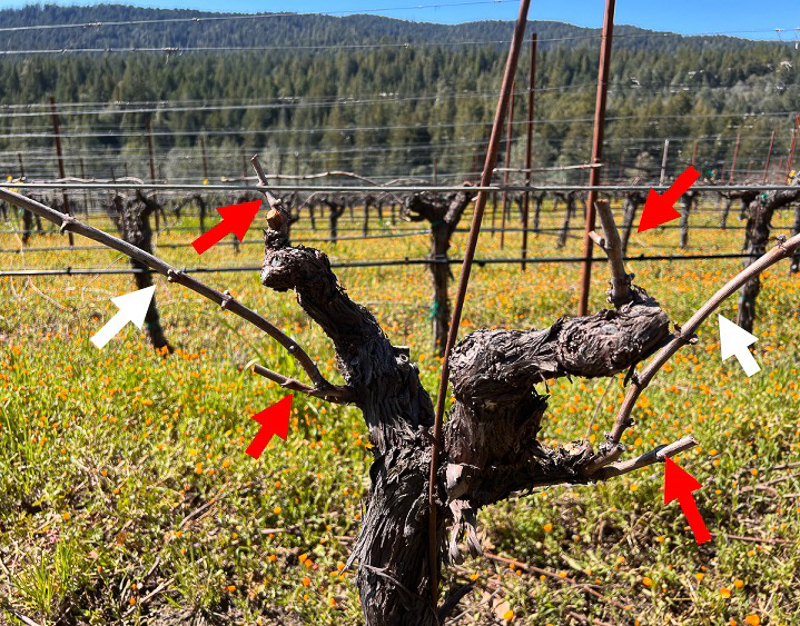

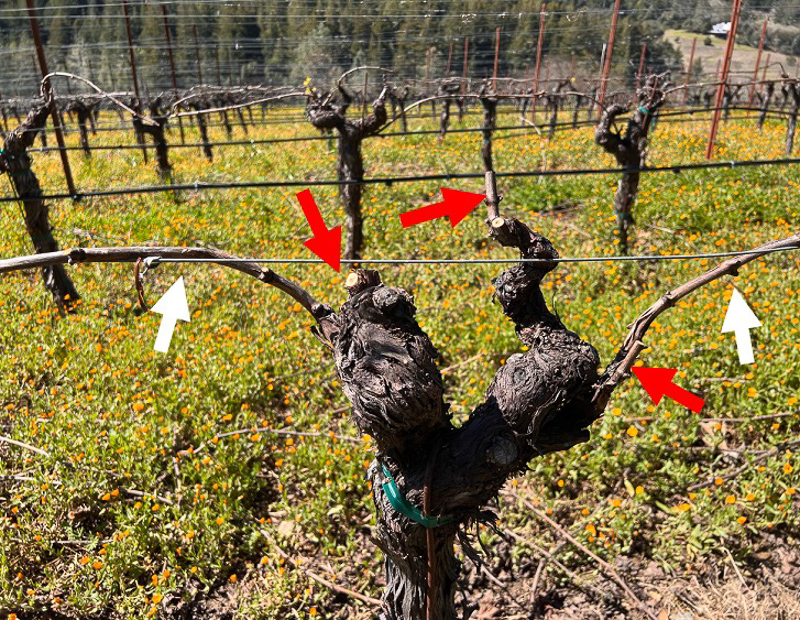

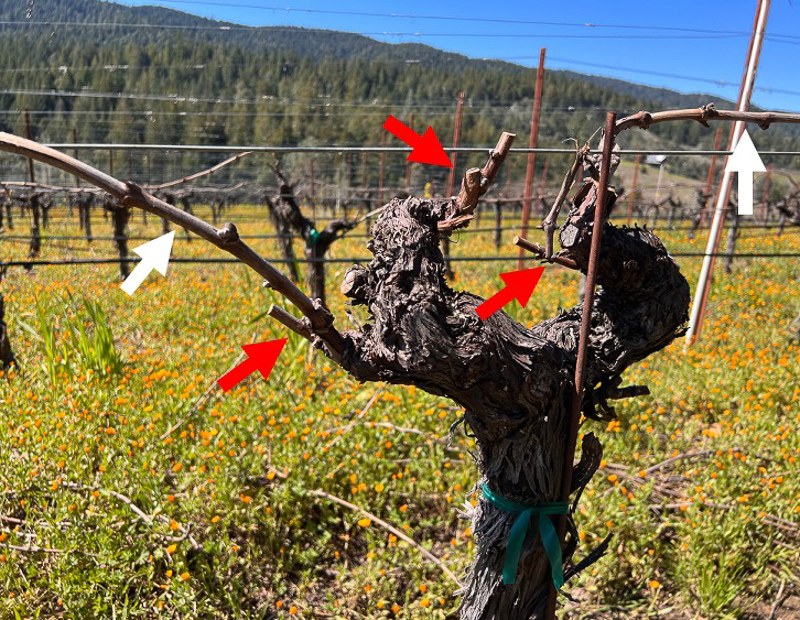

Cane pruning in pictures

Pruning isn’t terribly glamorous, but it’s an essential part of viticulture. The vast majority of vineyards are pruned one of two ways: cane or spur.

Cane is where there are no permanent arms (or very short ones), and each year a one year old shoot (the cane) is tied down onto the fruiting wire to provide the buds for the next season’s growth. In spur pruning, there are permanent arms (cordons) which have short spurs of one or a few buds from which the new growth comes from. Spur pruning is a lot easier, but isn’t suitable for varieties that have low basal bud fruitfulness. For example, Sauvignon Blanc is most fruitful at bud positions 4-6, so if a 2 bud spur is left, then the shoots that grow may not bear many grape clusters. Hence Sauvignon is almost always cane pruned.

The other issue with spur pruning is that sometimes positions on the cordon can die, leaving a gap in the canopy. Or the whole arm can die. Sometimes a spur-pruned vine is later converted to a cane-pruned one.

I recently had some time in a freshly pruned (cane pruned) vineyard so I picked 10 vines and photographed them, to illustrate the choices that pruners make. No vine is the same and with an older vineyard that may not have been pruned perfectly in the past, pruning choices can often be a compromise. The most common cane pruning is called a double Guyot, with a cane laid down either side of the vine trunk on the fruiting wire. But sometimes just a single cane is laid down, and in other cases three or four canes might be laid down on two fruiting wines, where higher yield is required. Most often, a replacement spur is also chosen, but this is not compulsory. It just gives the pruners more choice the following year: often the replacement spur will bear a cane ideal for laying down the following year because it is closer to the head. The first choice a pruner must make is which two canes to lay down. They should be of moderate vigour: the diameter of your little finger, not your thumb. Then the replacement spur should be chosen, if this is used.

There’s an increasing realization that pruning can affect the lifespan of the vine. Ideally, the pruner should respect the desire of the vine to branch, and keep selecting canes heading out in the same direction, with the cuts each year made on the same side of the vine to help maintain sap flow. Any cut made should leave the same length sticking out as the diameter of the wood cut away: this is because the vine doesn’t heal well and there is a little die back, known as the cone of desiccation. This die-back needs to be kept out of the trunk because it impedes vascular flow. It’s ideal to have the replacement spur just below the cane selected because it then produces a nice cane for the following year, and this process can be repeated, always making cuts on the same side, ensuring that it’s mostly one-year-old wood that is removed. Here are the 10 vines I photographed.