Zuccardi Valle de Uco: thrilling Argentine wines from Sebástian Zuccardi

‘My grandfather started our company in 1963,’ says Sebastián, who is the third generation of Zuccardi. ‘My grandmother is still working in the company – she’s 93, and every day she goes to the winery, apart from Tuesday where she goes to the hairdresser.’ The three generations work together. Sebastián himself started working in the vineyards, and then moved to the winery. ‘I want the wines to talk more of what we do in the vineyard,’ he says.

Bonarda is very special to him, because it’s the first wine he made himself, from vines his grandfather had planted in Santa Rosa in 1963. It was the 2009 vintage. Phil Crozier came to the winery, and Sebastián showed him the wine: Phil liked it enough to buy the lot. ‘Bonarda is the second most planted grape in Argentina, but for many years was considered a bad grape,’ he says. ‘No one paid it much attention. And when you go to the low altitude areas where the biggest volume is made, Bonarda is the most planted grape. Generation after generation of growers saw the adaptation that Bonarda had to the place.’

It gives high yields, and normally it’s planted in low altitude areas to the east of Mendoza. But Sebastián has made a point of planting some in every high-altitude vineyard that he’s been involved with in the Uco Valley. ‘I believe this grape is part of the DNA of the place.’

‘Bonarda taught me an important lesson,’ he says. He made his first Bonarda in stainless steel and then matured it in old oak, because no one had much confidence in. But because Phil Crozier had bought all of it, Sebastián was suddenly full of confidence and aged the 2010 vintage in new oak. ‘I killed the wine,’ he recalls. The lesson it gave him was that you can’t vinify everything in the same way. ‘Cabernet Sauvignon is a grape that can receive oak. Malbec is sensitive to oak, and Bonarda is extremely sensitive to oak. Bonarda gave me a lesson that we can make wine without oak, and that oak is not the most important thing in a wine.’

I asked Sebastián about his attitude towards whole-bunch ferments. ‘I work a lot with whole bunches, but I try to avoid carbonic maceration,’ he replied. ‘I love wines with carbonic maceration, but I think the vinification talks more than the place. If I have to criticize something on Malbec, it sometimes lacks a little bit of backbone. One way to build that backbone is with whole bunch. But in order to avoid the carbonic maceration, there are two ways of doing this. If we have time, we put the whole bunch in, crush with our feet. We use about 30-70% whole bunch. If I have no time, I destem. I use whole berries: I never crush the berries. You always have to be very careful with recipes. If you make a Cabernet with whole berries you are going to have whole berries, but with Malbec this never happens.’

‘The traditional way to work is with the sorting table for grapes and the destemmer, and sorting tables for berries. When Malbec crosses the destemmer, the berries crush. So if you have a sorting table for berries you oxidise everything. I do a sorting table for bunches, and then either put the whole bunches into the vat or destem into the vat. With Malbec, the tannin structure is extremely sensitive to oak and oxygen. If you have too much oxygen during ageing you lose the tension of the wine. The way I work is I try to avoid too much oxygen in my winemaking.’

I asked him whether he is interested in the new grape sorting technologies that allow winemakers to hyper-sort, such as optical sorters. ‘I’m not interested,’ Sebastián replied. ‘I believe that today this is a technology that is extremely expensive, and in three years will be common. So if you pay for this today there is no sense. But the other thing is I believe that when you work with clones and you select a lot, you are making the wines more uni-dimensional. Wine doesn’t need to be perfect; it has to be an expression of the place. Why in a place where we have own roots and our own massale selections, do we have to be so extreme in the classification in the winery? Today we have sorting table of bunches that we use in difficult years. We take out the leaves from the vineyard, but then I’m not interested to do a rigorous selection. The wine has to be the expression of the complex place.’

Is picking late a problem in Argentina? ‘I think harvesting in time is maybe the most important decision for a vineyard owner,’ he says. ‘If you make everything good in the vineyard, the harvesting time is extremely important.

‘Picking time is one of the most important decisions, especially in the style of the wines you want to make. The perfect time of harvest doesn’t exist. Every year I spend more time deciding the harvest time. A bad decision in the harvesting time can never be fixed in the winery. So my most important job is choosing the right time.’

Has he ever picked too early? ‘What is early and what is late? I try to have my own picking time, and I’m not looking at people around me. I harvest earlier than the average. But it is not just important where you start; the other important thing is where you finish. For me, we grow thinking that Malbec has a big window for harvest, and for me this is a mistake. I try to start at the right point, but I harvest very fast. The capacity of crush in my winery is four times higher than in a normal winery, because when I start I want to pick everything quickly. It is nice to talk about 11.5% or 12% alcohol, but our area has lots of sun. 11.5% is not OK for the average. My challenge is to see the sugar and acidity and to go to the vineyard to taste the grape. But it is also important to look at the forecast, and what the vineyard looks like. All the winemaking decisions are taken in the vineyard.’

‘My macerations in the winery are very short. I macerate for 12 days, or 15 days. If you have good viticulture, and you harvest at the right point, the good things are going to move to the wine very fast. Then, because I don’t like too much oxygen, I take the wine off the skins. Some years, I take the wine off before the fermentation is finished.’

THE WINES

Zuccardi Valles Torrontes 2018 Salta, Argentina

This is pergola-grown Torrontes from 1800 m, fermented in stainless steel. Harvested early to keep acidity. Lovely stuff: a bit pithy with nice precision. Focused with bright citrus fruit and a bit of pith. Lovely subtle bitter hints, with a mineral dimension. 90/100

Zuccardi Apelación Chardonnay Tupungato 2018 Uco Valley, Mendoza, Argentina

13.5% alcohol. From 1250 m altitude and alluvial soils. Elegantly aromatic on the nose with fine, delicate citrus fruits. The palate is bright and focused, with good concentration of refined citrus with a hint of toast, a fine spiciness, and a slight crystalline saline quality. There’s a real freshness and harmony here, with mineral undercurrents weaving through the poised fruit. Finishes taut and long. This could age well. 93/100

Zuccardi Valles Bonarda 2018 Valle de Uco, Mendoza, Argentina

Bonarda has its origin in Savoie. This is from three Uco Valley vineyards at 1300-1400 m. Fermented and aged in concrete. Very floral with bright cherry and raspberry fruit. Bright red fruits with lovely juicy fruit, and it’s a bit bloody round the margins. Fresh, fruity and linear. Grainy and detailed with lovely precision. 93/100

Zuccardi Apelación Cabernet Franc 2017 Valle de Uco, Mendoza, Argentina

Chalky, gravelly edge. Rounded and supple and fine with nice fine-grained structure and supple, expressive, juicy blackcurrant fruit. Elegant, fine and expressive. 94/100

Zuccardi Apelación Malbec Vistaflores 2017 Valle de Uco, Mendoza, Argentina

Vistaflores is at 1000 m in the Uco Valley, and there’s no calcium carbonate in the soils. Ripe and supple with floral black cherry fruit with some spice and a bit of grip. Sleek, with a hint of sappiness. Lush but well defined, this is fine and precise, but it also has some flesh. 93/100

Zuccardi Fosil San Pablo Chardonnay 2018 Valle de Uco, Mendoza, Argentina

This is from a special place in the Uco Valley, 200 m from the Andes at 1400 m. It’s the last vineyard to be harvested, at the lowest alcohol. There’s 60 cm of topsoil then stones with calcium carbonate. In 2016 they didn’t irrigate here: it is a really different place to the rest of Mendoza. Taut and mineral with a bit of nutty, toasty richness and nice fine spicy tension. There’s grainy structure and good acidity (cloudy fermentation). Expressive, with citrus, pear and mineral notes. 93/100

Zuccardi Aluvional Paraje Altamira 2015 Valle de Uco, Mendoza, Argentina

70% concrete, 30% oak. Ripe and dense. Vivid black fruits nose. Spicy with a hint of tar, graphite and chalk. The palate is bold and fresh with grippy structure and nice precision. Quite drying and tannic with lovely concentration and freshness. 93/100

Zuccardi Aluvional Gualtallary Malbec 2015 Valle de Uco, Mendoza, Argentina

70% concrete, 30% oak. Supple and bright with good concentration. Nice green hints here with sweet raspberry and cherry fruit. Open and expressive with fresh acidity. Real brightness here, and some tar and spice on the finish. 94/100

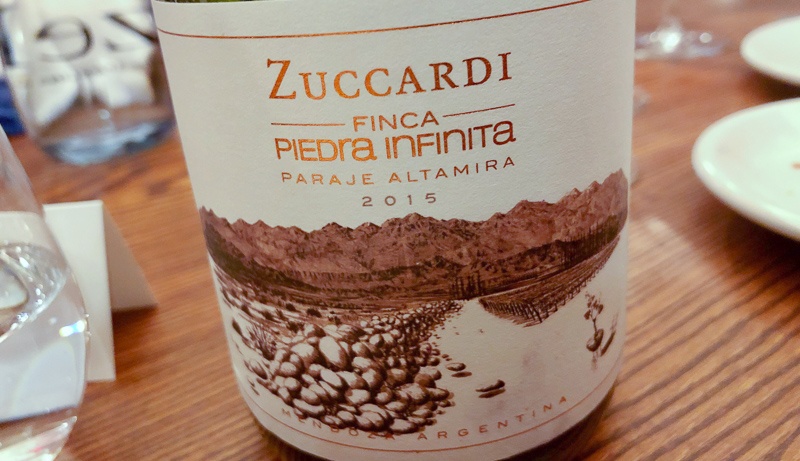

Zuccardi Finca Piedra Infinita Malbec 2015 Valle de Uco, Mendoza, Argentina

100% concrete fermented, 50% whole bunch, aged 70% in concrete and 30% in 500 litre barrels. Very fine and precise with bright black cherry and raspberry fruit. Supple, grainy and chalky. Expressive and refined with brightness and good acidity. Primary and linear. 96/100

Find these wines with wine-searcher.com