How has social media influenced the work of wine journalists? And what social media strategies should wineries take?

This is a written version of a talk that I gave at the #winecom congress on communication and wine in Pamplona, November 12 2021.

There are different sorts of communicators

Newspaper columns

Wine writing is dead! What I mean by this is that the old model of wine writing is dead. When I first started drinking wine, all the major newspapers had a specialist wine column. They hired people on professional salaries to produce this weekly column, which was a nice gig to have. These wine writers would have plenty of time for other activities, like writing books, taking press trips or doing a bit of TV work. But it was a closed shop: there were only as many jobs like this as there were national newspapers. There are still a few people who make a living primarily from a newspaper column. But because of the changes in the media, vanishingly few newspapers can pay a specialist columnist like this a full-time salary.

Critics

Over the last few decades, there has been a rise in the number of specialist wine critics. Their primary job has not been to write about wine, but rather to rate individual wines. While he wasn’t the first or only critic, Robert Parker and his publication The Wine Advocate is the most famous critic and his way of working has acted as a model for many others. Initially working alone, the world of fine wine has become so large that it’s too big for one critic to cover comprehensively. So Parker hired others to help lighten the load. The Wine Spectator, another influential American publication, also began rating wines and hired its own team of critics. One of Parker’s hires, Antonio Galloni, left his employ amid some acrimony, and set up his own critic venture called Vinous. And James Suckling left the Wine Spectator and started his own critic venture, again with a team of specialists. The Wine Enthusiast, another US magazine, is also in the business of rating wines. So now we have a lot of people acting as professional wine critics, all tasting within their own specialist areas. They are kept busy with thousands of wines to taste and rate each year, so writing is secondary to them.

While Parker’s business model was to be a consumer advocate, and sell his reports directly to consumers, the new critic publications have further revenue streams. These include events (where producers pay to take part, and consumers pay to attend), selling stickers, and charging retailers and producers for using their ratings.

Low barriers to entry

The Internet has opened up the wine communication landscape. The first big change was the arrival of the internet itself. Wine websites began to pop up, but perhaps the biggest change was that suddenly enthusiasts could get in touch with each other through discussion/bulletin boards. Communities of like-minded people began to coalesce. I remember the excitement of the wine bulletin boards in the mid-to-late 1990s, and how professionals and amateurs gathered together to talk wine, crossing international and professional boundaries.

This was a big change. In the past, the discussions were vertical. Experts used their columns to speak down to their readers, in a vertical, one-way transmission of information. Now they became horizontal: a conversation. Print media began to operate online, but usually the internet presence was secondary to print. Then along came blogs: these were for a while the new stars. But the advent of social media stopped them in their tracks.

The big change was the arrival of social media. Facebook, then Twitter, and then Instagram. These are the specific social media that have had most impact on wine communication, although there are others.

Now anyone can be a wine writer. There are fewer professional, full-time writers paid a salary by a newspaper or magazine. There are more writers, though – even some of them who work full time but fund the activity themselves (they have no need to earn a proper income), and many who write a bit on the side of another job. The barrier for entry is much lower, and most of the gatekeepers have been removed. This reflects the fact that the media landscape has changed.

The changing media landscape

Previously, print dominated the media landscape. Newspapers and magazines had a specific business model. They sold information and entertainment, usually with a low cover price. The real money was made from advertising. The professionally generated content primarily acted as a peg to hang advertising on. Journalists were hired to write things that people needed to know, or wanted to read – information and entertainment. Then, the recruitment of all these readers was used as a peg to hang advertising on. When I started commuting to work by train back in 1992, the majority of my fellow passengers bought a newspaper. Now it is rare for people to buy newspapers: circulations have plummeted. Commuters are now looking at their phones. Instead of reading professionally generated content (the work of paid journalists) people are reading user-generated content on social media. Social media’s great skill is that people provide content for free, and lots of it, regularly – there is a mass of content to hang advertising on, and the tools themselves are addictive, with regular ‘rewards’ such as likes. The algorithm is tuned to give people what they want to see, and it’s almost as if the feeds are tapping straight into our brains’ evolutionary architecture to keep us interested and scrolling.

The exodus of readers from newspapers and magazines to social media has been followed by advertising spend, and this is what has really changed the media landscape. Now, the duopoly of Facebook and Google has swallowed up a vast amount of the available advertising money. Newspapers and magazines have gone online, but either they are free to access and get lots of traffic, but nothing like the advertising revenue they used to get; or they have gone behind paywalls and thus make some money, but have far less traffic. They have less advertising money and less budget to pay writers.

Meanwhile, wine communication continues, and social media has opened up new avenues for content creators.

The various platforms constitute a communication toolkit, each with an ability to do something different. The communications landscape is now quite an interesting one.

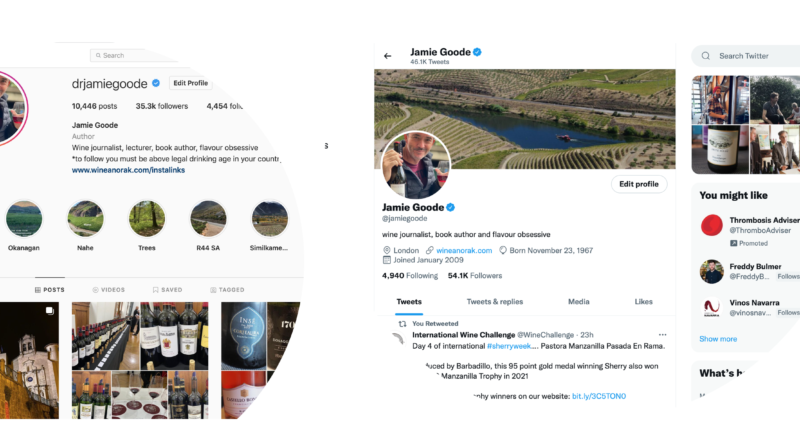

On the one hand we have already-established wine media people making effective use of social media to increase their audience. Then we have newcomers who have established themselves solely through social media, or whose careers have grown up in the age of social media so this has been part of their presence. And there is the exception of Instagram, where some people have established themselves solely by their reach on this platform.

One of the keys of using this new media toolkit well is to have your own identity. And to build an effective brand, there should be consistency in the sort of messages and content that are being published.

Influence is much more distributed these days. Rather than just a few key voices, there are many people each with their own tribe – each with their own way of communication.

One other point to note is that there is now lots of free content out there. So why would someone pay? Many media organizations use paywalls, and even independent journalists are putting their output behind a paywall, looking to gain subscribers. The advantage is that this gives an income stream – the disadvantage is that it reduces reach. People will generally try to get free information before they pay for it.

One consequence to the new distributed nature of wine journalism, which is a consequence of the low barrier to entry, is that the signal to noise ratio is diminished. There’s just so much content out there. This can make it difficult for new entrants – and even genuinely good new voices – to establish themselves and find their audience (or perhaps more accurately, for their audience to find them).

No one pays for quality journalism, but are journalists now more efficient also? Because the rates of pay haven’t gone up in 20 years, journalists are getting less for their work than they used to. But perhaps they have adapted, and with the help of new communication tools are working faster and more efficiently, with more output.

What should wineries do?

The great thing about these social media tools is that it is now possible for wineries to tell their own story. This is a chance to be in control of the message, rather than relying on others. Of course, there is still great value in third-party endorsements – you can’t review your own wines! – but if you have a good story, you can tell it, and you can connect with the people who are drinking your wine and who are curious about where it has come from.

One of the main ways you have to connect with customers is the bottle that is in front of them. We often forget this, but the consumption occasion can be used as an opportunity to start a conversation. Of course, not everyone opening a bottle of your wine is going to spend time looking at the label. But one of the advantages of the pandemic is that it has revived the QR code, which was hailed a decade ago as a great idea but never caught on. But now that all that is needed is for someone to point their phone camera at a code, suddenly it’s a lot more practical, and because of checking in at venues, pretty much everyone has experience of using these codes now. This makes the whole relationship with customers at point of consumption a much more realistic goal.

Be slightly wary of some influencers: they promise a lot but often can’t deliver, partly because of comment/engagement pods. There are influencers with genuine influence, and there are others.

Distribution sells wine, so reach the gatekeepers. People can only buy the wine that is in front of them, and the low hanging fruit in marketing terms is connecting with and influencing (often through a third party like a trade-focused journalist) the people who decide which wines to buy and list. Reaching consumers indirectly through reaching the trade is a smart use of marketing spend. Trying to reach consumers directly is often expensive and ineffectual. Remember: ‘normal’ consumers don’t read about wine or buy wine magazines – it’s far too abstract and arcane. But they do like to taste wine, and drink wine.

Take advantage of third-party endorsement by propagating it through your own channels. You have to use it: the value is not necessarily in the endorser’s own reach.

Then we have the age-old problem of segmentation. Segment the market: there is no ‘consumer’. There are different sorts of consumers, and the same person can behave like one consumer group on a Tuesday, and another group on Saturday. And, once again, the biggest segment is people who don’t want to read about wine because it is too abstract.

The impact of the internet and social media on the way we communicate has been significant, and I can’t help but feel that there is still more change to come. We have to be smart, flexible and swift to move, but while the medium is partly the message, the message itself hasn’t changed too much – it is all about people communicating, whatever medium is at hand.