Interviewing Daniel Daou, who is making remarkable wines from limestone terroirs in Paso Robles, aided by some smart science

Brothers George and Daniel Daou are from Lebanon, but their family left during the civil war in the 1970s and relocated to France. They moved to the USA to study and later started Daou Systems, which was an intranet system for the health service. They sold this and pursued their passion: wine. Their search for perfect Cabernet terroir led them to the Adelaida district of the Paso Roble wine region where they have planted 26 hectares of vines on clay/limestone soils. I caught up with Daniel Daou to taste his wines, hear his remarkable story, and also to chat about the very scientific approach they have taken in the pursuit of making fine wines.

Jamie Goode (JG): Tell me a bit about your story.

Daniel Daou (DD): My brother and I were born in Lebanon with a Lebanese father and a French mother, who was born on a French island and grew up in France. She went to Lebanon because it was a great vacation spot and her family owned some properties there. My Dad was Mr Lebanon in 1951, and she fell in love with him at the airport and got married two weeks later.

When the war started in 1973 the first rocket that exploded in Lebanon unfortunately hit our house. I almost got killed, and so did my brother and sister. I still carry the facial paralysis from being hit in my face and I have shrapnel in my heart and legs. My brother was in a coma for 48 hours and almost didn’t make it.

Having been brought up in a French culture at home, speaking French, and having gone to French school, and having French citizenship it made it easy for us to emigrate to Paris and then Cannes, where I grew up until I was about 18 years old.

I was very interested in computers. We moved to the USA and attended the University of California San Diego, where my brother majored in electrical engineering and I majored in computer engineering. We ran out of money. When and our family left Lebanon we were well to do: our father started a factory business manufacturing furniture for furnishing hotels. But we lost our money, and we got down to living in the USA with $20 in our pockets, and we had to get jobs to pay for our college education. Our parents emigrated to the USA in 1986, and brought their last money with them. We took their last $50 000 and started hi-tech company to build intranets and computer networks. At the time there was nothing like that. We were fortunate enough to build a successful company. 10 years later, in 1997, our company was sold and we ended up retiring. I was 32 years old when I retired.

JG: What’s the connection with wine?

DD: Growing up in France, I developed a real passion for wine at a young age. My dad drunk a bottle of wine every day. He would have half at lunch and half at dinner. I heard him talk about life, family, philosophy: all the things that inspire my brother and I today. In my early 20s I started collecting wine, and I came to the realization in my mid-20s that my true calling was to be a winemaker, to the shock of my family. Our grandparents had a huge olive farm, and we had the best memories going there, picking olives and chasing cows and chickens. After I retired from my company there was no question in my mind that I wanted to make a top class Cabernet Sauvignon.

I started an eight-year journey to find what I thought would be the perfect terroir for growing Bordeaux varieties. I took an engineering approach. The conclusion I came to was a simple one. One, you need the right kind of soils. Most high-end vineyards in Europe share a soil in common, which is prevalent in Europe, argile calcaire. These soils allow you to dry farm, something that is almost impossible in California. The limestone subsoil retains water from the rainy season, and feeds just enough water to the roots. Two, you need to go beyond fruit and alcohol. I developed my palate in Europe so I like earthiness and minerality. Often I found California wines were climate driven. I was always tasting fruit and alcohol, but I wanted more than that: I wanted minerality. Last, I wanted to make unadulterated wines. I didn’t want to acidify the wine. I wanted to make as natural a wine as possible, and these soils allow you to do that.

These are the only soils that really provide what I have been talking about. In warmer climates like California you reach your physiological ripeness at higher sugars if you don’t have these soils. By the time physiological ripeness occurs you have lost your acid and you are forced to add a ton of tartaric acid to bring down the pH and stabilize the wine. In my opinion, you take away the innate balance and end up with a wine that’s lab manufactured and bites you at the back of the jaw and scratches you in the throat. All these things drove me to look for these soils, but the only problem with these soils is that they don’t exist in California. The only place you find them is on the west side of Paso Robles in the Adelaida district. This is where we are located.

Climate is the other component of terroir. The climate in California is warm. It’s warmer than France, and many parts of Europe. It’s like a bell curve, though: you want to be warm enough to ripe every year, but you don’t want to be too hot so you achieve high alcohols and jammy character. You also don’t want to be too cold and rainy, so you have pyrazines and you also only have two good vintages out of 10. So the key was to find a climate that was somewhere between Pauillac and Napa. That is exactly what we found.

Our vineyard is the only one in California that is at 2200 feet elevation, but only 14 miles from the cold Pacific Ocean. In 2019, Pauillac saw 4 days at 40 C. Napa saw 11 days. Paso Robles saw 28 days. Our mountain saw zero. Our average maximum temperature is right between Pauillac and St Helena. It’s the perfect climate to achieve ripeness year after year.

14 years ago, I packed my bags and moved up to the mountain we had just purchased. There was no water or electricity. I erected a 1000 square foot modular building and planted the first 26 acres myself. This is the story, in a nutshell.

JG: What is different about your approach in the vineyard and the winery?

We have a disruptive approach when it comes to the wine industry. Our Soul of a Lion – if you had asked anyone 10 years ago – can a Paso Robles high-end Cabernet compete with California, people would have laughed. Soul of a Lion has outsold every Napa blue chip in California two years in a row, besides one winery, Opus One.

There is a subjective way and an objective way at looking at wine quality. The subjective way is a critic looking at a wine. From an objective standpoint, there has always been a direct correlation with higher phenolics and higher quality. If you look at Bordeaux, what is the difference between a good vintage Bordeaux and a bad vintage Bordeaux from the same Château? The good vintage is going to have more colour, a better tannin structure for more ageabilty, and better aroma. All these things can be qualified today as phenolics, and we have the technology to measure them.

There is a direct correlation between higher phenolics and better wine. I measured 700 of the best Bordeaux wines made across the world, and we have not found anything at the top of the heap that gets within 30% of what we get on our mountain. More importantly, we have found we are able to deliver a product that in the USA sells for $50 a bottle that has more phenolics than every first growth in the best vintages, and more phenolics than 99% of every Napa Cabernet that sells for $300 for $50. This is a wine that can age for four or five decades, that has balance, elegance and freshness, but at the same time has tremendous colour. It is not over extracted. This has allowed us to be, today, the fastest growing winery in America.

Our vineyards are planted at high density, up to 9000 vines/hectare. Today we have 80 hectares planted, and we are in the process of planting another 80 hectares in the next three years, and this will be the max. This is all within a mile of our winery, so it is the same terroir, same elevation and same slopes. We are 98% planted to Bordeaux varieties, and the other 2% is Chardonnay.

JG: How do you manage the vineyard?

We have a team of about 18 people, and everything is done by hand. The only thing we use tractors for is to spray for mildew. The vineyards are either dry farmed or deficit irrigated. My whole philosophy is about vine balance.

We have a four-to-five foot canopy that is hedged so we have very even photosynthesis occurring to ripen these grapes. The way I deal with vine balance, is because of the high density of planting I reduce the number of the clusters per vine to about 20% of what they can actually carry. This leads to even ripeness year after year. I do use cover crop. I didn’t used to, but we have some extremely steep slopes and I was worried about erosion. We don’t use them everywhere, but we use them especially on the slopes, to keep them together. We are 95% organic and are sustainably certified. The only non-organic product we haven’t found a way of doing without is for powdery mildew. The mildew pressures here are extremely high. We had a neighbour who tried to go organic and they lost their entire crop two years in a row. We use sulfur until June, but then it sometimes gets too hot and you don’t want to use sulfur when it gets hot. So we use conventional for about a month. We give two shots of organic fertilizer a year, one at the beginning of the season and one after harvest to replenish the nitrogen in the soil.

JG: what about fruit zone leaf management? How do you deal with the heat?

I developed a protocol about four years ago that will allow us to handle a difference in temperature of 5-7 F, and not have any damage to the grapes or the canopy. The reason I developed this protocol is because in 2017 we had one of the most severe heatwaves we have seen in a long time in the west side of the USA, even going as far as Oregon. I realised we had a problem we had to deal with. The protocol is a three-pronged approach for dealing with heat waves and row orientation. One, the vine has an immune system, and I found a product developed in Italy called BluVite, and it activates the soil microorganisms and strengthens the immune system of the vine. If you take two humans of the same age and put them in the Mojave desert where it is 130 F, and one is tip top healthy and one has compromised health, who is going to last longer? We tested this product and found that the leaves are greener and the shoots are thicker, and the vine is more healthy when there are heatwaves. We measured the temperature and found that there is a difference of 3-5 F just because the vine was treated with this product. It allowed it to handle the thermal stress better. Last year (2020) was a great test because it was the third warmest on record and we had four heatwaves. After two years of trial all of the vineyards were treated with BluVite.

The second approach is that there’s a product invented years ago in Israel that is a shade cloth, and blocks 40% of UV rays, allowing light and air through. It prevents sunburn. Every row in our vineyards is covered on the afternoon side with the shade cloth that also protects the canopy and not just the fruit. Where we are located, sometimes there are rows that are a little bit southwest facing, and because of this the sun could cause sunburn, and here we don’t remove leaves, and for a week we will put shade cloth on both sides when there is a heatwave. In blocks that are east or north facing we pull leaves on the morning side so there’s good aeration. It all depends on the row orientation. Using the shade cloths we saw another 3-5 F difference, so we are now seeing a 5-7 F temperature difference across the board.

The third prong of our approach is measuring soil moisture. I found that during the morning the moisture would start at 100%, but then during the heat of the day the root zone would dry up to zero. I though this meant I would have to water. But the next morning it was back up to 100%. I thought one of my guys had watered, but no one had. I did the same again, and the water went down to zero and the following night it got replenished. This explained to me why in Europe there are so many vineyards on limestone soils. What I did notice is that during a severe heatwave, when it goes on for a few days, there is not enough time to replenish the root zone. The vine is smart, and it wants to survive, so if it can’t get water from the air it will cannibalize itself and take water from the grapes. So if there is a heatwave I give microbursts of watering, just during the day, in order for stopping the moisture from staying at zero percent for too long. Last year we had four heatwaves and we received the most pristine grapes ever, despite the fact that most of the region had canopy and grape sunburn.

JG: When you pick, have you looked at the variation in ripeness in the berries?

You can average sugars, but you cannot average flavours. I have done lots of trials on this. Most winemakers play the laws of averages because they don’t have vine balance. I have gone to other vineyards and taken every cluster on the vine, and measured sugars. The difference can be 8 or 9 Brix sometimes, so you have raisiny, pruney grapes and others that are green. When you put them together, the wine tastes terrible. I build up the canopy, then hedge it to even up photosynthesis. I always make sure that I reduce the number of clusters. My goal is one degree Brix difference at most. I find the results of berry sampling are not consistent, but when I take a whole vine, and pick all the clusters, and look at them this gives me better data.

Assuming that your vines are healthy and virus free, and they are not terribly old, do you think you could use the canopy vigour or trunk circumference as indication of where there is natural variation in your vineyard? In some blocks the soils might be a bit more bony, and the vines might be growing differently there. You have 80 hectares so there might be some blocks that are quite different.

I have a map where I indicate the pockets. For example, I have this block where 20% of it, the edge, is struggling because it is too rocky, and the canopy is not growing too well. In this case I apply 15 tons/acre of organic compost, and I work it into the soil. And it’s crazy that within a year, everything pops up and gets back to normal. The oldest vines are 13 years old, and the average age is 9.

JG: Is there an age of these vines where you notice that they are clicking in, and suddenly you are getting the site and not just fruit?

DD: Yes, usually around 7 years old. At this age I see such tremendous minerality.

JG: What’s your approach to sorting?

DD: Usually the day before I harvest the grapes, my team goes through the entire block, and if we notice anything that is not 100% good we just drop it. When the grapes arrive at the winery, we are the only winery in Paso that has a Pellenc optical sorter. We have two sorting mechanisms. For our estate fruit, which is really clean, we rarely use this. But for the fruit we buy in, we will do double sorting. In the past, if I’ve seen too much dust on the grapes, I will wash them. I like to work with clean fruit. We go through an optical sorting system. We tend to eliminate anywhere between 5 and 15% of the grapes on the optical sorting system. I have it running at a high level so anything that doesn’t look perfect just gets rejected.

JG: What do you do with the stuff you reject?

DD: We feed it to the cows. We give it away. After the fruit is sorted it goes into the tank. We have a unique site. In places like Bordeaux you don’t really have high phenolics because of the weather. Winemakers have to resort to doing more maceration to extract more tannic structure. We have the opposite problem: our site is so high in phenolics that usually within 3-5 d after we finish cold soak we are draining. The wine would be undrinkable. I have tasted hundreds of wines, based on my sensory profile. For the wines that I found balanced I came back with an algorithm that looks at the entire phenolic components. It says when you take the tannins, and you divide that by the overall phenolics (reactive phenols, RPs), I noticed that as soon as you get over 52% it means you have extracted too many tannins. I came back with a profile that says, this is the range you want to be in to make elegant fresh wines that are drinkable on release, but which can also age for decades. When you are fermenting a wine it is virtually impossible to taste the wine and decide whether you have enough tannins. You can’t do it. So instead, I balance out the wine while it is being created so my blending becomes less of a corrective process. If you create a balanced wine in the first place, then your job becomes easy.

JG: I’m fascinated with extraction regimes. The rate of extraction matters, and it matters whether it is in the aqueous phase or the alcoholic phase. The size of the fermenter is critical, because this presumably determines how much oxygen is present. If you are fermenting in a big tank, you will have less oxygen present, and this is needed in fermentation to help form the pigmented polymers with the anthocyanins and the tannins. Post ferment macerations are also interesting: if lots of tannins are extracted early on, the pulp can fine out some of these later on. This is all really interesting: it’s a brilliant idea to try to quantify what gets you into the right zone. Tasting a fermenting wine is just guessing.

DD: The thing to understand is that there is a difference between anthocyanins and anthocyanins. The key thing is you want bound anthocyanins. This is when an anthocyanin molecule binds to a tannin molecule. When this happens, the colour does not precipitate. Many winemakers finish alcoholic fermentation, do malolactic, and then hit it with 40 ppm SO2. The minute you do that, the binding process stops and you give up 20-30% of your bound anthocyanin. We have the highest bound anthocyanins on the planet. There is a direct correlation between bound anthocyanin and texture. And there is a correlation between bound texture and intensity. This texture is very important. I have done a lot of trials, and I have found a way to increase anthocyanins in ways most people don’t understand. Commonly, people finish malolactic fermentation and then add SO2. One trial I did is instead of applying the regular dose, I noticed that during that malolactic fermentation that’s when the mechanism for binding this colour is happening. You don’t want to go through it too quickly. I took a barrel and applied 2.5 g of malolactic bacteria, and then I did three other barrels where I reduced it down to 0.2 g. The lowest dose took two months longer to go through malolactic fermentation, but it bound 20% more colour. This is why I don’t add any SO2 for six months after primary fermentation. I found that for six months the binding process continues. All my wines are aged at 50 F and I use only 10 ppm of SO2 during elevage. I use temperature to control bacteria versus a lot of SO2.

The more oxygen you have, the more you will bind anthocyanins. So the worst thing you can do is ferment in a huge tank, because you will miss out binding the anthocyanins.

JG: What size tanks do you use?

DD: Five to ten tons. I find this is a great size to work with. I can’t do regular pump overs because things move so quickly that if I’ve just done a pump over and can’t drain for 4 or five hours, for me a half hour difference might mean it is over extracted. I have created a special system where I do open circuit pump overs like a mini delestage, and I use a special device that oxygenates the wine even more. If I do a closed circuit pump over I have to wait four hours.

I will typically do 3-5 days cold soak, because I like to extract my colour before I extract my tannins. The minute the wine starts fermenting, I drain as early as 2 days and I’ve gone as long as 7 days, but I don’t every go to dryness. I can’t: it would be too much tannin.

When you are fermenting wine with higher phenolics, the more of a chance there is of a stuck fermentation. But all of my wines are dry. When I first started making wine here it was a disaster: the phenolics were so high, and combine that with heat and the fatty acid membranes of the yeast cells get damaged. Now I have a technique that allows me to go to dryness, to below 0.5 g/litre. First, I got lucky: I collected grapes and sent them to Italy and they identified 100 different yeasts on them. We tested all of them. It took us three years. I never forget the phone call from them when they told me they’d found a yeast, number 20, they’d never seen before. It is a Saccharomyces cerevisiae strain that won’t die at 104 F and stabilizes colour better. I hit the jackpot with this yeast which we use for all our wines. It is called D20, and is sold in 35 countries. I wanted a yeast that can handly higher temperature. But during my research I found a product called NoStop, which is basically fatty acids. So now I inoculate with our yeasts then later I add fatty acids to protect the yeast cells.

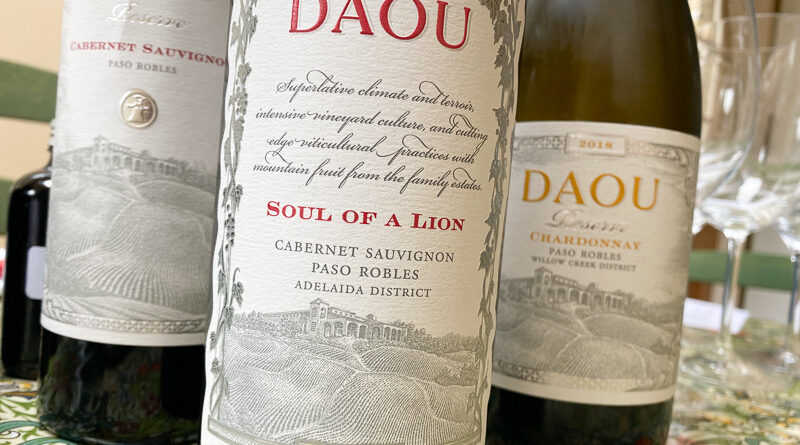

THE WINES

Daou Estate Malbec 2018 Paso Robles, California

Concentrated and quite intense, but not overly tannic, with immense structure – but it’s tamed, and the tannins don’t stick out. There’s some sweetness to the fruit, which is blackberry and black cherry with some floral notes, as well as quite a bit of new oak, although this integrates well and adds something to the texture, as well as a touch of vanilla and pastry on the finish. Stylish and intense. 94/100

Daou Estate Cabernet Franc 2018 Paso Robles, California

Intensely coloured, this is a concentrated but beautifully put together expression of warm-climate Cabernet Franc. It has a lovely sense of freshness, as well as lush but not jammy blackcurrant and blackberry fruit. The oak adds structure, but doesn’t intrude at all, and the overall impression is one of superb balance. There’s plenty of tannic structure here, but no over-extraction, with a lovely depth to the palate that suggests a long evolution ahead of it. 95/100

Daou Estate Micho 2018 Paso Robles, California

There’s some gravelly depth here to this wine, which has sleek blackcurrant and blackberry fruit, with a hint of chocolate and some fine leafy notes in the background. Beautifully constructed with ripe fruit and firm but fine tannins, all pulling together very well to create a fresh, yet fully ripe wine with significant ageing potential. 94/100

Daou Estate Cabernet Sauvignon 2018 Paso Robles, California

Pure, fresh, quite supple and intensely coloured, with bright blackcurrant fruit, as well as some richness on the mid-palate. The fruit absorbs the new oak quite easily, and the result is a sumptuous, dense Cabernet, but one that avoids over-ripeness or over-extraction. Has the stuffing for a long ageing, but is already delicious now with its supple blackcurrant fruit. Just the tiniest hint of greenness, which is appropriate for this variety. 94/100

Daou Estate Cabernet Sauvignon Clone 4 2017 Paso Robles, California

This is firmly structured with some grippy tannins sitting under gravelly blackcurrant fruit. Dense, vivid and a bit edgy, it combines sweet ripe fruit with some grainy tannin and the impression is of a wine that needs some time. Great concentration with some sweet cherry notes on the fringes, and lovely blackcurrant freshness on the finish. 93/100

Daou Estate Cabernet Sauvignon Clone 169 2017 Paso Robles, California

Hints of earth, tobacco leaf and spice on the nose as well as sweet blackcurrant fruit. The palate is concentrated, but has freshness and elegance, with a sweet edge to the gravelly blackcurrant fruit and some notes of cedar and spice on the finish. This is beginning to open up a little, and it has real charm, as well as substantial stuffing. 94/100

Daou Estate Soul of a Lion 2018 Paso Robles, California

Such refinement here, allied to concentration. Sweet berry and blackcurrant fruit on the nose with subnotes of tar, cedar, fine spices and a slight leafiness. The palate has depth and structure, but also an openness: it’s far from being a monolith. Sweet cherries, blackcurrants, fine spices, some cedar, a touch of chalkiness, and also a touch of alcoholic warmth. Still has freshness, and the structure suggests it has a long future ahead of it. Really stylish. 95/100

Daou Estate Soul of a Lion 2016 Paso Robles, California

Assertive blackcurrant and blackberry fruit on the nose with some hints of herb and cedar. The palate is really sleek and textured: there’s no shortage of structure, but the ripe, lush blackfruits win. There’s a freshness to the finish, and a hint of mint, and it melds into a smooth, luxurious finish. Just beginning to soften and harmonise, and should age nicely. 94/100

Daou Estate Soul of a Lion 2013 Paso Robles, California

Aromatic with cedar, tar, dried herbs and sweet blackcurrant fruit. The palate has a savoury, finely grained earthy hint and some lush but fresh black fruits. Hints of olive and spice, with a nice balance of sweet and savoury. The fruit profile is really ripe, and there’s a softness to the mid-palate. It’s drinking very well now, with some softness and mellowness. Will be interesting to see how it progresses from here. 93/100

Older notes:

Daou Reserve Chardonnay 2018 Paso Robles, California

This is from the Willow Creek district. 14.5% alcohol. This is bold but fresh with rich peachy fruit and a touch of citrus brightness. There’s a richness to the mid palate with a smooth texture and a slight oiliness, as well as some notes of cashew and honey, finishing with bold pear and crystalline citrus notes. A very luxurious, rich, quite harmonious Chardonnay. 94/100 (£57.80 Hedonism)

Daou Reserve Cabernet Sauvignon 2017 Paso Robles, California

14.8% alcohol. Sweetly fruited nose with some blackberry and blackcurrant character. It’s sweetly fruited but well defined on the palate with ripe, rich black fruit and some creamy texture. There’s something very seductive about this, with it’s sleek ripe fruit, and a nice chalky, grainy edge adding savouriness and interest. This has lots going for it. 93/100 (£55 Hedonism)

Daou Soul of a Lion Cabernet Sauvignon 2017 Paso Robles, California

15% alcohol. Adelaida district. This is a powerful, concentrated, multi-layered and really seductive. There’s a lovely gravelly edge to the ripe blackcurrant fruit with masses of concentration, and some creamy, spicy depth from the oak. Massive concentration with well managed tannins and nicely integrated oak. A blockbuster, icon-style Californian Cabernet and really enjoyable and impressive. It’s certainly ripe, but it works so well. 95/100 (£166 Hedonism, £150 Woodwinters)

Find these wines with wine-searcher.com