Domaine Hugo and Offbeat Wines: naturally made in a Wiltshire winery, these are some of the UK’s most compelling wines

Jamie Goode and Lisse Garnett meet two exceptional producers who together make some of the best wines on offer in England today

Domaine Hugo is a badly kept secret in Michelin-starred circles – Hugo Stewart’s superb sparkling wine is born of chalk, without added sulfites, on land in conversion to organic at Botley’s Farm on the Wilshire/Hampshire border. Hugo’s first project at Les Clos Perdus in the Corbières Hills, now biodynamic, was an organic conversion too – surprisingly he finds it easier to farm organically here in the UK.

Daniel and Nicola Ham run the winery onsite at Botley’s. Here they make Domaine Hugo’s wine, a number of contract wines and their own range entitled Offbeat Wines. Daniel was the winemaker at Ridgeview for over four years before a similar stint at Langham Wine Estate, he is the man responsible for creating the distinctive Langham style that is winning so many plaudits today.

There is an easy affinity between these three: a palpable calm born of a naturally shared philosophy. Doctor Nicola and Dan are highly trained marine biologists, and this is evident in the way they have honed their winemaking and in the sapid vibrant nectars they produce. Hugo is a well-spoken modern-day Greenman, almost pagan in his respect for the land. Collectively their approach has birthed an exceptional canon of wines that are alive, energetic, fresh and pure. All this without the use of sulfites AND in England.

DOMAINE HUGO

Hugo Stewart is an honourable farmer, a genuine protector of the land which thrums with the beat of butterfly wings, birdsong and raptor calls. Hugo’s 100-acre farm precisely straddles the Hampshire Wiltshire border. It’s been in his family since the 1970s. A 100 acre arable farm is too small to make a living from grain so Hugo converted to breeding pigs back in the 1980s. When pork prices dived in 2000 he decided to give himself a year in the Languedoc and rented out the land to a neighbouring farmer.

He bought a ruin near Tuchan, in the Corbières Hills – which he describes as ‘Katy Jones territory’ (after Katy of Domaine Jones). One Summer a dancer friend named Paul Old came to visit: he’d just retrained as a winemaker in Waga Waga. Paul Old fell hard for the charms of the Corbières Hills and decided he’d like to grow grapes there. He suggested Hugo join him. Having just gotten out of farming in the UK, Hugo baulked, but thinking it through, had the intuition to see his flexible friend would probably make a really good winemaker.

Paul’s drive toward perfection – his precise dancer’s art – is expressed in the wines he produces. Today Les Clos Perdus, the domaine they founded, is highly acclaimed and makes wine from a number of diverse terroirs, including the Agly Valley in Roussillon. They had hoped to blend the old vine grapes they cultivated, but soon realised that was never going to work and now they make three entirely different wines. Tiny quantities are produced – they sell well from California to Tokyo. Nicolas Joly is a fan and friend.

By 2014 Hugo had had enough of sitting in front of his computer, an unforeseen result of his and Paul’s success. He made up his mind to return home and have a go at making English wine. He decided that a 3-acre long fallow field earmarked for herbs might do well with Champagne varieties. Chardonnay, Pinot Meunier, Pinot Noir and Pinot Gris were planted in 2016. Originally he had wanted to make a still from the Pinot Gris but he opted for a fizzy field blend instead.

Hugo Stewart: I really like the Pinot Gris; it ripens more easily and gives the blend a bit of a lift. It is anything between 5 and 8% and its surprising what impact that has. My first English vintage in 2018 I took to Langham where Daniel was working on the advice of another friend.

Daniel Ham: The grapes were phenomenal, I said to you didn’t I, don’t expect to get fruit like this every year, they were just exceptional – these tiny little bunches, tiny little berries, no rot whatsoever.

HS: At Les Clos Perdus, Paul was absolutely meticulous about not bringing anything in that was not 100%. Our first two or three years we were chucking anything that wasn’t absolutely perfect. We went organic quite quickly and it was quite heartening as the Carignan in particular gets oidium quite easily. After the fourth year of trying to tame this beast – I said I think we are going to have to rip it up – then thought let’s give it one more year. And it started getting a bit of odium and then suddenly it just disappeared!

Jamie Goode: Do you think that could be because some of the preparations you were using acted as elicitors of induced systemic resistance so the vines are primed? It’s a potential explanation for why resistance suddenly kicked in after infection?

HS: You certainly felt that they’d built up resistance, that that was what had happened. Of course the big problem round there is Esca – (fungal trunk disease) – anyway back to here..

This is the original planting, I decided three or four years ago to plant another plot. What I notice is that the big problem on chalk is iron and chlorosis – there is very little iron but Meunier seems to be more tolerant to a lack of iron and I researched this – that seems to be the case. There is no disease – even last year when people were struggling in this country we had a good crop and everything that came into the winery was clean.

Lisse Garnett: It’s quite fresh here – do you think the wind circulation is key?

HS: Yes, as time goes on I realise that this chance site is a really good one – it’s really well ventilated, it’s not too exposed, yet you do get a breeze. The only place we have ever had any frost damage is right up in the top corner where there isn’t the air circulation.

DH: Yes it keeps dropping down into that valley below the new forest and the frost just drains away.

HS: We then planted a bit of Pinot Gris and some Pinot Blanc – just 4 rows – but these newer plantings are in stark contrast to the original – the original field had been fallow for quite some time whereas the next field where I planted the second plot was in intensive agriculture.

When I returned from France I decided to go organic across the whole farm so I took the land back. Because it’s been in intensive agriculture its really lacking in quite a lot of minerals across the board, we put in quite a lot of elemental fertilisers like magnesium. We have just done a leaf analysis and its fine here on the original fallow plot but on the previously intensively farmed plot its really struggling. That’s why it’s been so slow at getting established. To a certain extent anything you plant here is slow at getting established because of the chalk and the exposure.

JG: So it’s really interesting – your ecosystem was working already on this original plot.

DH: I mean just purely walking through the two fields initially, you could feel some give to the soil in plot 1, a sponginess – whereas down there it’s just solid. It is getting there, there has been a huge amount of cover crops and nutrients going back into the soil. But from the beginning this definitely just felt like it had more life to it.

HS: I cultivated it initially without any competition but I use the same French viticulturist I used in France and he said you have got to put a cover crop of clover and birds foot trefoil. The problem is getting it established, you don’t want to plough it up – you can get direct drills. The problem is with a small hectarage outside a main wine growing area is getting people to do stuff. I know Duncan McNeil has a meter-wide direct drill but it’s way too far for him. It’s really hard chalk.

You’ve got to get the fruit really ripe and if you’ve got too much, you don’t get the ripeness and last year was the first year I green harvested which felt counterintuitive at the time but I realise the benefits of it now after a season.

DH: It’s the most difficult thing dropping fruit not just in terms of the heartbreak but because it’s difficult – you have to take time to select the retained bunches.

JG: This place is so alive, there is wildlife everywhere. Do you notice variations in the vineyard where different plants are growing, as in those naturally growing plants are acting as indicators of differences in the soils and subsoils?

HS: There are certain places where we get more docs and mallow – its quite variable. We graze sheep just after harvest and into winter, we’ve got nine Shropshire sheep. They are used in plantations because they keep their heads down, they don’t have any goat in their ancestry which would be a disaster as they would eat up the fruit. They are quite well known for keeping their heads down. There is a vineyard in Essex is experimenting by putting the sheep back in to leaf strip.

JG: They do that quite a lot in New Zealand, you’ve got to get them out in time or otherwise the grapes are gone. When you see the fruit zone and the sheep have been through, there is nothing there. It’s a great idea and it would be nice to have them present in the growing season too – rotational grazing might work. If it does work it would be fantastic.

HS: Also I won’t have to mow the grass. I have about 20 different types of clover which we mow and that provides mulch. Initially were taught to avoid competition with the vines but then we discover all these different plants are helping one another.

JG: A lot depends on the individual site, under there you have an ecosystem that’s working, that’s functional.

THE WINEMAKING

Dan and Dr Nicola Ham are both marine biologists, and they run the winery at Botley’s Farm where they make Hugo’s wine, their own wines plus a number of contract wines. Dan is a Plumpton graduate, Nick has a PhD in Marine Biology. Despite their considerable achievements they are not forthcoming about themselves. I wondered who they were when we arrived at Botley’s…so unassuming, standing quietly in the dappled shadows. Dan is also a qualified marine biologist; his Plumpton Degree came later. And yet this understated pair make some of the very best English wines I have ever tasted.

Dan Ham: I started working at Vineworks whilst I was studying at Plumpton then I went to Ridgeview where I became a winemaker for four and a half years. When Mike Roberts passed away I was Assistant Winemaker and Simon Roberts became very poorly for 6 months – I was only 6 months out of College but I ended up taking over the operation, about 300 tonnes a year.

LG: Err bloody hell weren’t you bricking it when that level of responsibility landed in your lap?

DH: I didn’t really think about it, just got on with it. I moved to Langham in 2015 and I was there for about 5 years. We moved here in 2020.

Nicola Ham: We were living in Salisbury anyway – I was commuting to London. We have three kids; we had been living at Langham in a farm cottage where I had my maternity leave but then when I returned to work so we had to move to Salisbury so I could commute to London. We were both doing jobs we loved but the lifestyle wasn’t sustainable, the children were at Dan’s parents for most of the week and we were both knackered.

LG: How did you both meet?

We met at a small Consultancy in Bath, Dan was working there in the holidays and I was working there full time. We then went to live in New Zealand for three years where I did my PhD. I was working for a non-profit doing oil spill response. It was emergency response travel which wasn’t conducive to having children.

LG: What is your philosophy for the winery?

NH: We are certified organic, moving toward biodynamic, we want to move it towards low or now sulphates, spontaneous ferment – people are realising that it’s the way to go. The big contract wineries find it really hard to deal with smaller volumes, they need a big throughput to make it worth their while.

LG: Is that quite profitable doing little odds and sods?

DH: We couldn’t have done what we are doing without that, we don’t have tonnes of cash.

JG: Do you charge per litre?

DH: It’s quite difficult, there is so much variability, we are treating the grapes differently from year to year. We do everything from Traditional Method to Pet Nat, absolutely everything.

NH: The hardest thing is managing people’s expectations, the contract we draft is like an upside-down triangle with a risk calculation on it – inoculate, don’t inoculate, SO2, no SO2 etc, everything that’s high risk, so we can ask where on that list do you want to be? So then we’ve got it in writing.

DH: A lot of people love the idea of natural wine but they never actually drink it. With contract winemaking there is also a strict timeframe whereas our own wine can just sit for as long as it needs, be it 2 or 3 or 4 years. So that side of it is pretty stressful.

LG: So you designed your own contract, does it work?

NH: Mostly, I think some people don’t really know or are unable to communicate what they like in a wine. We have to try and translate what is in their head into an actual wine. The other thing is we do everything by hand – everything takes a lot longer than it would in a normal winery facility and I think a lot of customers don’t realise that. Also it really is just us.

LG: Do they end up being involved in every decision-making process?

NH: Yes we try to involve them in every decision.

JG: Do you use a mobile bottling facility?

DH: No we do everything by hand, Pet Nat’s – everything – you get used to it. Nic’s only here from 9-3 pm too because of the school run and she does it all.

LG: Which press is your preferred?

DH: This is a new pneumatic press we only got about two or three months ago, it got to the point where we were being forced to use the Coquard, it just felt wrong to be working at that for 6 or 7 hours so we use this for anything up to two tonnes, it will work really well from about 1.7 to 2 tonnes, anything outside of that becomes really difficult so all of Hugo’s fruit pretty much goes into the Coquard and the longer aged still wines under our own label, Chardonnay, Pinot Blanc, which we started pressing on 12-14 hour press cycles so really really slow and gentle.

The beauty of the Coquard is we don’t have to settle the juice then because the juice that’s coming out is so clear and I think part of that is the actual mechanism itself but also because the juice is flowing across so many surfaces before its settling. So for me that is one of the best things about using this press as opposed to the pneumatic, it’s the clarity of the juice. You get this purity without using enzymes, without having to settle and I think that’s why in Champagne you are seeing more and more people going back to using the traditional presses. This is really the only point where we are pumping anything – after that pretty much every movement is by gravity because as soon as you start to put it through the pump the oxygen pick up is just so high.

LG: What are these tanks?

NH: We’ve got stainless steel tanks and we’ve got some fibreglass as well.

JG: Is that because they are cheaper?

DH: Actually there are no cheaper these days but what I like about them is the temperature. In fibreglass during September and October, fermentation kicks off straight away whereas in the stainless steel it takes ages to get going and then the temperature rockets – it gets really hot. We use these for maceration too and we have found the reduction is lower in this than in the stainless steel.

NH: They’re nice because they are slightly translucent, you can see what’s going on. You can monitor the ferment. A majority of the fermentations are happening in terracotta, working with them is very different. The rest of the ferment goes into at least fifth use oak. All of the sparkling needs it to soften, cold stabilisation happens naturally, unlike in tanks. It gives us the chance to just tuck things away and do elevage for a year to two years. What we would really like to do is move toward doing the second fermentation of Hugo’s wine with the fermenting must.

HS: Yes – it seems nuts to me, you are going to all these lengths and suddenly at the last minute you put this proprietary yeast and sugar in it.

DH: We’d put aside two barrels of the blend from 2020 with the idea of fermenting with the must and a portion of the juice was separated out. Nothing else went reductive but this 50 litres we had portioned, by the time I realised the bulk of the wine had fermented through. But I think it was fate because now we have these two barrels that were left and they have just evolved and become something really special with that extra elevage, we are really pleased.

JG: Could you freeze your must?

DH: I’ve spoken to a lot of people and they say don’t mess with your secondary fermentation. You’ve spent all this time – and temperatures are dropping really fast at that time of year so you put stuff into bottle and it just sits there. We do a Col Fondo of Hugo’s like that and it works well but we are only going to two bar pressure with that, the pressure is much higher, more like 4 with trad method. It’s a difficult thing to get right.

JG: Is yours a vintage wine Hugo?

HS: We are building up reserves, I’d like to build up two or three years, we are putting more back so we can have a blended wine rather than vintage, there is 18% Reserve in the 21. The 2020 that spent a year in barrel – that’s amazing.

DH: So we ferment everything spontaneously, no enzymes even on the contract side. That is one thing we are not prepared to compromise on at all. Sulphur is used in tiny quantities but we never use that in our own or Hugo’s wines. I don’t think we could now – I think the longer you go through your winemaking journey it becomes a much bigger deal if you had to add sulphites. It seems like a poison to us now, sometimes when we are disgorging for contract stuff we use it and it’s a horrific chemical, really nasty.

HS: Also it’s a disinfectant and you are putting a disinfectant into a glass of wine.

DH: I’m not such a purist that if we absolutely needed to use sulphur we wouldn’t, if we started to get mouse in the wines or something like that, we would. We are not in the business of making faulty wine but I think it’s the pinnacle of the craftsmanship as well, if you can make wine with no additions then it’s a bit like being a carpenter and working with hand tools instead of power tools, there is a beauty to it.

Let’s taste the wines….

Domaine Hugo Traditional Method 2019

JG/12% alcohol. Pinots Noir, Meunier and Gris plus Chardonnay. This is complex and expressive with lovely toast and spice notes, alongside ripe pear and peach as well as some apple. This has a lovely limey flourish with nice spice and pear fruit. Long, complex and expressive with amazing depth. 94/100 (c. £50)

LG/ Rich, toasty and complex – fecund with fruit – proffers peach and pear, lightly bruised red apple, oily almonds and a subtle hint of tarragon. The mousse is mouth-filling, fine and frothy – a touch savoury and profoundly textural – salty, layered and deliciously long – Sublime. 96

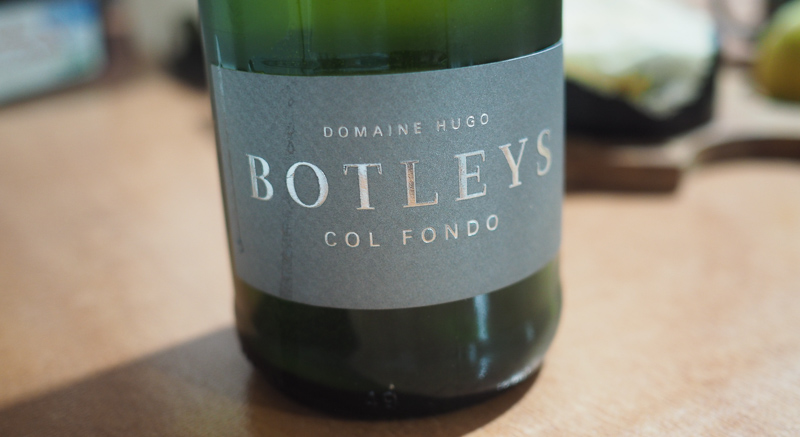

Domaine Hugo Botleys Col Fondo NV

JG/10.5% alcohol. Second ferment was with the following years fermenting juice in bottle, with the base wine spending a year in tank. It’s 2020 but not declared. Wonderfully fresh and refined with a nice drinkability, and depth of pear, cherry and citrus. Textural and expressive with lovely fruit, but also some nice spicy framing and complexity. Lovely savoury twist on the finish, too. 92/100 (c £30)

LG/Super sapid and fruit forward – biodynamic, fermented in stainless steel and not disgorged – full of fruit – apple, pear, cherry, grapefruit – Fine, fresh and zippy yet rounded – its more orchard fruit than citrus – dry and very slightly savoury – tannic on the tongue – tiny mineral twang of toast tinged savouriness on a softer finish – Long 92

UK agent: Under The Bonnet and Scala Wines.

Off Beat Wines

Offbeat Wine Prospect NV

JG/10.5% alcohol. Mostly from 2020. 43% Solaris (whole bunch, foot trodden, macerated 5 days), 43% Bacchus (hand destemmed, foot trodden, macerated 5 days) – both 18 months in barrel without topping up so developed flor. Then 7% Orion, 4% Madeleine, 3% Phoenix. Aromatic, fresh and fruit with sweet grape and cherry notes, as well as come crystalline citrus. The palate is crystalline and expressive with pear, melon and peach as well as some depth, finishing fresh and citrussy. So beautifully expressive. 93/100 (£27)

LG/Floral, pear and red apple – this is a deliciously textural and salty – pear drop note, candied grapefruit and red apple – round and smooth – sour cherry – fresh peach – salty melon – floral and so stimulating! 92

Offbeat Wine 369 NV

JG/Three vineyards, three varieties. A blend of Pinot Noir (45%, 2021 macerated 5 days then oak), Pinot Meunier (41%, carbonic for 3 weeks then oak, including 2021 and 2020) and Triomphe d’Alsace with some whole bunch in juice, 14%). Fresh, direct, lively and sappy with redcurrant and red cherry fruit with some sour cherry and a bit of smokiness on the finish. Nice sappiness with a green edge and good acidity. Has a nice acid lift, which helps bring the freshness to the fore. 92/100

LG/ Sapid and fresh with punnets of wild strawberries, blackberries and cherries plus a deliciously distinctive savoury textural dimension – dry and very slightly tannic. A batsqueak tendril of woodsmoke enriches the super sour cherry finish 92

Offbeat Wine Field Notes 1 2020

JG/ Direct pressed Pinot Blanc juice with whole cluster Pinot Noir, sealed up for three weeks and this is the free run juice. Juicy, sappy and fine with fresh red cherries and a touch of cranberry. This is expressive and bright with lovely textural cherry and strawberry fruit, showing precision and some sappy detail. So elegant and expressive. 94/100

LG/ Elevated supple carbonic zippy freshness – sweet red strawberry, blackberry and crunchy sour cherry, a portion of this wine is aged in acacia – incredible sapid freshness and a silky satin texture runs to a gorgeous grainy sour cherry finish 93

Offbeat Wines Wild Juice Chase NV

JG/Triomphe d’Alsace (a hybrid teinturier) planted in 1984, and left a bit wild. Semi-carbonic 2020 then barrels for a year. Then juice from 2021 harvest was bottled with this. Tart, juicy, spicy and fizzy with lovely bright raspberry fruit and some fine spicy notes. This is a little wild, but beautifully expressive and fun. Bright acidity. Superb stuff. 92/100

LG/Tart, dry and sapid, vivid with blackberry and crunchy sour apple, a chicory-tinged Cherryade. 91

Offbeat Wines Field Notes 2 2020

JG/This is the pressed whole bunch portion of Field Notes 1. Lovely expressive cherry fruit with some almond notes, and also ripe pear. There’s a slight peppery note, but also some richness of texture with a smooth mouthfeel and fine detail. Very silky and seductive in an elegant style. There’s a slight savoury clay-like undercurrent. 93/100

LG/ Silky and satin smooth on the tongue with strawberry, pear and ripe cherry – lifted and superb – rich with almond oil and fresh cherry blossom – ripe and sapid with a deliciously salty and textural – delicately savoury finish. 94