The Jessica Julmy interview: transforming Galoupet in Provence – regenerative farming meets alternative packaging

Website: https://www.chateaugaloupet.com/en-gb/home

Jessica Julmy is in charge of Galoupet, a Provence winery recently purchased by Moët-Hennessy. Previously, Julmy had been the commercial director of Champagne Krug. The changes she has introduced at Galoupet are noteworthy for two reasons: first, they have decided to farm the property regeneratively; and second, they are using a novel flat-profile plastic bottle for their second wine, Nomade. I caught up with Julmy together with fellow journalist Rupert Joy at the Living Soils Forum in Arles to interview her about this interesting project. I began by asking her how she’d begun this journey to regenerative farming.

Jessica Julmy (JJ): When I arrived, Galoupet was, at the risk of using a cliché, a sleeping beauty. The previous owners felt they could make more money from it as an events space. Besides doing conventional agriculture they had stopped investing in the vineyard. This translated into lots of missing vines. From the outset we discovered there wasn’t much organic matter in the soils, and because we had so many missing vine stocks many of the plots didn’t meet the cahier de charges for Côtes de Provence. So we knew we had to replant 60% of the vineyard. As for the winery itself, they had refurbished it and recently finished the renovations, so there was a hefty cost for the large events space. So you come to Galoupet and there’s a huge terrace, a ballroom, and the winemaking area was more for large-volume bulk wine.

Before this I was commercial director at Krug and I’d arrived in 2013. I lived the undusting of Krug, where what helped us a lot was discovering Joseph Krug’s notebook and delivering his vision. I thought, who knows, maybe I have my own Joseph Krug? I looked in the archives but only found a bit of history here and there. But LVMH is the fifteenth owner so it has changed hands a lot of times. To this day I haven’t found an official foundation date. But there was a tipping point when I realised that Galoupet actually appears on one of the first maps of France, dating back to the mid 18th century. So I thought, OK, there is something unique about this place. 15 different owners, the French revolution, forest fires and the place has never wavered. I have been looking at this purely as a viticultural excercise: yes we have 69 hectares of vineyard all in one place; yes we are a cru classé in Provence; but we also have 77 hectares of protected woodland. This is when we realised we have this unique ecosystem. Combine that with the deep conviction that I have that it is the responsibility of a big group like LVMH to invest the money and take the risk, and I thought I had this opportunity to start from scratch.

We have this holy trinity: a magical place, the resources of a group like LVMH, and the fact that I can’t break anything because I’m starting from scratch. I know I am going to uproot and plant, so I can think what do I want my fine wine to look like? When you uproot it is a perfect moment to do terroir analysis. I am not set to a recipe. Also, when you know that the packaging is such an important percentage of a winery’s carbon footprint, I don’t have a brand code in terms of my bottle and I can look at every step of the way, at what is going to make a fine wine but also what is more respectful to the environment.

Jamie Goode (JG): In terms of the vineyard specifically, what did you do?

JJ: We began our conversion to organics on August 1 2020. By the 2023 harvest we should be certified organic. But when you are in Provence, I really feel that this is the tip of the iceberg. It’s clear, sunny and dry, and there is a lot of wind. We want to go a step further. We reached out to partners. It is critical to me that we don’t have one big founder or cellar master. When we have this ambition it would be ludicrous to stay like this so we have been reaching out to different experts. We reached out to agroforestry experts: what can we plant where? Not only to move away from monoculture, but creating that natural corridor between the vineyard and the forest. Then at the base of the pyramid we have bees, and biodiversity: how do we bring bees back into the forest? We want to regenerate the flora and the fauna in the forest and see the impact on the vineyard. Then we are also working with a cover crop expert to find out what the perfect blend of seeds is that is good for our soils: how do we bring back organic matter and humidity?

And another aspect at the back of our minds is that in Napa people really appreciate water, but in the South of France it’s hard to believe that we’ve been in drought since March, because for anyone connected to the Canal de Provence it is like it rains every day in the south of France. We have a reservoir in the protected woodland. How do we refurbish this, and how does our water engineer work with our forestry expert? It Provence, when it rains, it pours. But since the soil is so arid it just runs off.

JG: a big challenge in an environment like this is, how do you avoid bare soil? Because water is scarce, everyone is scared of competing with the vines. Yet part of the regenerative toolkit is growing other stuff in the vineyard.

JJ: This is where our cover crop expert is great. We don’t know the perfect blend: is it more or less mustard; is it more or less clover; more or less buckwheat? And is it every row? Since we did the soil analysis with Emmanuel Bourguignon figuring out the three micro terroirs we have, we know that the recipe isn’t the same across the vineyard. We need to adapt them to the different soils: we have more colluvium in the bottom part of the vineyard, then a bit more schist at the top.

JG: Have you adapted the trellising or training of the vines? Have you gone with bush vines?

We haven’t changed that yet. Right now we are mostly obsessed with regenerating the organic matter in our soils. Then, as we go along, we are determining which grape varieties we will plant, depending on the micro terroirs.

JG: In terms of the agroforestry, are you growing trees within the vineyard plots?

JJ: Yes. But for us, throughout this, we didn’t want anything to work in silo. There was one meeting when I thought this is worse than herding cats, because we have all these experts coming together, and of course they always see the church in the middle of their own village. There are the bee experts that want this, and the bat experts who want that. We are wanting to create this link with this wealth of biodiversity that we have. We are working with a biodiversity association to recreate the biodiversity within the protected woodland.

JG: Have you got any metrics you can measure progress with?

JJ: This is where we started doing the counting – a full audit – of the flora and fauna in the forest. This was so we can see how we are improving it over time. Then we thought it’s a shame we have that metric in the forest, but not in the vineyard. This is where we reached out to the LPO. It might appear that they specialise in birds, but they have helped us count the different species that are regenerating in the vineyard.

Rupert Joy: I can see that counting bees and birds is relatively straightforward, but it seems that you have inherited a vineyard that has not been nurtured as you would like. Do you have a plan for the soils where you are going to get them to a point that you can not till them? What stage are you at with the soils, and how are you measuring it?

JJ: For me it is a 20 year plan. When you are talking about the wine industry, or nature, it can’t be any less than a 20 year plan. We are starting from scratch, essentially. Our first priority was deciding what the most urgent action, and that is a 10 year plan in terms of what needed uprooting and replanting. We uprooted 13 hectares after the harvest of 2019, and 6 hectares after the harvest of 2020. Now we have spaced this out to 2 hectares a year until 2031. We will not be at full capacity until 12 years. It is a slow burn to give us time to craft the quality of the wine that we want. This is why this year and the next two years the Criu Classé represents just 7% of our total vineyard capacity. We feel that to make this quality we can only count on a certain amount. Intrinsically this allows us time for the benefits of organic viticulture and integrating agroforestry, and all that. We will also be looking at the organic matter in the soils. One other aspect is that within the 69 hectares of vineyard 65 are AOC Côtes de Provence, and 4 ha are IGP. We realised that we wouldn’t commercialise the IGP so we started looking at the grape varieties of tomorrow: these 4 hectares are dedicated to new varieties. Part of the experiment is against disease resistance. The others are for rising temperature.

JG: In addition to the vineyard, are you also looking at the packaging and winery options too?

JJ: Yes, and this is why it has to be a 20 year plan. The 10 year plan in terms of uprooting and replanting – this was our first investment. In terms of the health of the soils, we are measuring this with our cover crop experts and agroforestry experts. But also a big part of the project has been knowing that we want to invest in the winery itself for higher quality wines.

JG: What’s the break even point, after all the investment?

JJ: It all depends on what you count and what you don’t. I’m very thankful for Moët-Hennessy: it does take time and it does take money. And trial and error.

One of the most challenging things has been this potential paralysis. If you insist on finding the perfect solution you don’t move. With the Galoupet Nomade, I was extremely attached to having a second wine. I love that our cru classé is only using our own grapes, and this will allow us to make a terroir wine, which isn’t a conversation you have in Provence. It isn’t a conversation you have in Moët-Hennessy, because we buy 80% of our grapes. I love this about the cru classé. At the same time I thought if I do all these things, what impact do I have if I don’t share it. No one wins if I keep it to myself, and that’s why I wanted a second wine where I had to get external grapes, and I could invest in the growers. This is why Galoupet Nomade has to exist. But this opened up the conversation on packaging. It is such a disruptive area because people have a lot of preconceived ideas. Find me one perfect solution that ticks all the boxes, and I’ll take it, but until you show me that, I’m going ahead. I have a wine that is not meant to age more than 24 months, I have a wine that’s not a spirit so alternative materials to glass are OK, and I have a wine that doesn’t have bubbles. I have stayed away from certain choices that keep too many people out of the conversation, and here the responsibility of a big group like ours is talking about it. How do we start the conversation? Smaller growers can’t.

THE WINES

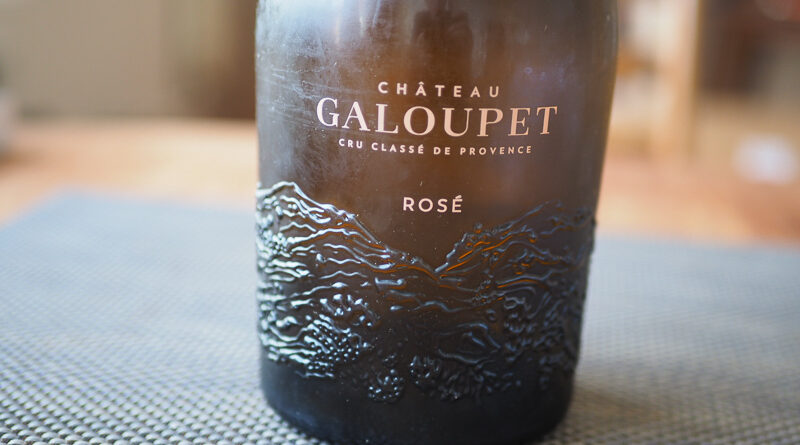

Château Galoupet Cru Classé Rosé 2021 Côtes de Provence, France

14% alcohol. Nice pink wax here, with coloured glass to protect the wine, which is rare now for Provence rosé. It’s supple and bright with lovely red cherry and watermelon aromatics as well as a touch of mandarin. There’s nice focus on the palate with fine spicy framing, a touch of structure, and compact but pretty cherry and citrus fruit. This is a beautiful expression of Provence rosé: it’s accessible and delightful, but there’s also a touch of structure and seriousness, too. Very fine, as it needs to be to justify this price tag. 94/100 (£46 Clos19, Hedonism, Tannico)

Galoupet Nomade Rosé 2021 Côtes de Provence, France

13.5% alcohol. This is packed in a flat profile ultra-light PET bottle weighing just 63g. Developed by sustainable packaging pioneers Packamama it is made from 100 % recycled PET and can be recycled after use in your plastic recycling bin. Pale pink in colour with an appealing fruity nose showing watermelon, mandarin and spice. The palate is fresh and textured: just what you’d expect from Provence rosé in very different packaging. 89/100 (UK retail is £22)

Find these wines with wine-searcher.com