On alcohol in wine, and attempts to remove it: a report on the state of play with no-alcohol wine

Let’s do a thought experiment. Imagine you have a stash of wines – maybe a small cellar of a couple of hundred bottles. When the time comes, you are looking forward to drinking these wines. Over the years you have bought wisely, and you can only imagine what pleasures await when you pop those corks.

Now imagine one night the wine fairy arrives, and through some magical process removes the alcohol from those wines without changing their taste. To what level, if any, would the absence of alcohol make you any less excited about these wines? Remember: the taste of the wines has not changed at all. No wine expert alive would be able to tell your wines apart from the full fat versions with their alcohol still present.

The answer to this thought experiment will vary by drinker, and by occasion.

Why do you like wine? Is it just the taste? Or is the alcohol important, too? And let’s not forget the consumption occasion. Wine makes certain social situations happen, and it expands others. We sit down to eat, but without wine at the table you might not linger in company as long as with wine. A bottle tasted in the right settings is much more enjoyable than the same bottle opened in a sterile setting or when there’s bad energy in the room.

If you are a wine lover, you are most likely drawn in by the flavour of the wine, but not just by the flavour. The stuff around the wine – the drinking occasion, the history you have with the producer, your knowledge about the wine, your past experiences, and even the glass you drink from – these all affect how much you like the wine. Whether or not you give the wine you are drinking any attention will also bear strongly on how you feel about it.

And there’s the alcohol. Our experience with wine almost always involves the ingestion of alcohol. In the wine trade, we are often tasting and spitting, but outside of this context evaluating or drinking wine goes hand in hand with the pharmacological transformation of our minds. The consumption of wine alters us; it changes our experience of the world; it changes our interaction with each other; it loosens our inhibitions; and with a favourable tailwind it can make us feel better about our immediate circumstances. As we drink, we open up to our fellow drinkers. It’s an incredibly sociable drink. We drink and we relax.

But sometimes alcohol gets in the way. Often when I’m drinking with wine friends, many interesting bottles get opened, and sometimes we get a little drunk, and then we don’t give the wines the attention they deserve, and there’s a chance we’ll feel sluggish the next morning. Or we might be driving, and not want the alcohol to impair our reaction times and judgements. Or it could be lunchtime, and we want to be in good shape for the afternoon’s workload. In all these cases, it would be great to drink the wines without the pharmacological effects of alcohol. And in some cases, our bodies might not be able to deal with daily drinking, so for health reasons we can’t consume as many of the bottles we have stashed away as we’d like. Australian wine legend Len Evans came up with his theory of capacity. Evans pointed out that we each only have so much drinking capacity in our lives, and so to drink an inferior bottle of wine is denying you the opportunity to drink a good one. ‘People who say, “You can’t drink the good stuff all the time” are talking rubbish,’ said Evans. ‘You must drink good stuff all the time. Every time you drink a bottle of inferior wine it’s like smashing a superior bottle against the wall. The pleasure is lost forever. You can’t get the bottle back.’

In this case, the wine fairy’s magic trick of taking out the alcohol and leaving the flavours intact would be welcome. Well, at least some of the time. While we are aware that alcohol can be problematic for some, we should be careful not to diminish the valuable social role that alcohol performs in bringing people together and helping them to engage with each other. We need more connection in our world, not less.

There is no wine fairy: visiting pioneering no-alc winery Carl Jung in Germany’s Rheingau

Unfortunately (or fortunately, depending on your viewpoint), it isn’t possible to remove alcohol from wine and have the wine taste the same, although many have tried to do this. And there’s nothing terribly new about attempts to make good quality no-alcohol wine, although it’s currently quite a hot topic in the wine world.

Last year I travelled to Rüdesheim, in Germany’s Rheingau region. It’s a pretty town, located on the Rhine with the dramatic vineyards on the slope of the Niederwald rising behind it. From the town you can take a cable car up to the top of the Niederwald and then look down across the vineyards to the town and the river. It’s a tranquil ride, moving slowing over the vines, and this is a big tourist attraction.

One of the dramatic features of the town is the Boosenberg castle, which dates back to the 12th century. Its tower, which at 38 m is the tallest building in Rüdesheim, has been owned by the Carl Jung winery since 1938. And this is why I was here: it was back in 1907 that Carl Jung devised a process for removing alcohol from wine, and so successful was this business that the winery is now solely focused on making alcohol-free wines. At any one time there will be a couple of tankers parked outside the winery, which is in on the fringes of the town, bringing wine to be de-alcoholized. Jung produce 15 million bottles of alcohol-free wine each year, usually on a contract basis (this is 65% of their production) rather than under their own label. So this seemed to be a good place to come and learn more about the challenges of making good quality wines without alcohol.

I visited with Bernhard Jung (pictured above). Carl was his grandfather, and Bernhard says that Carl’s breakthrough in devising alcohol removal technology was inspired by hearing about Himalayan expeditions. Mountain explorers found that water boiled at much lower temperatures at extreme altitude, because of the lower air pressure. Of course, alcohol can be removed from wine by boiling it, but at normal pressure the heat required to do this would kill the wine. What about using very low pressures – a vacuum – and then boiling the wine at low temperatures that preserved its character? So Carl worked out how to do low temperature vacuum distillation for wine, which is still today the most widely used method for producing low and no alcohol wines.

Talking the alcohol out of wine was quite controversial then. Bernhard Jung says that is grandfather was taken to court eight times by the wine control board, but he was never sentenced. He’d begun making no-alcohol wines for private clients, but then had his first commercial success in the 1920s and 1930s selling to the USA during prohibition. Business grew slowly, but in the 1960s and 1970s Scandinavia was a key market. And Canada also became important. These wines could be sold outside of the monopolies. Now the business is flourishing.

There are two distillation columns at Jung, one capable of 1500 litres hour and the other of 1000. The column we see in action, the older of the two has a column 10 m high, under vacuum, and the surface area of the fillers inside the column is almost as big as a football field. This large surface area creates a thin film of wine, and the steam coming up (at low temperature; remember this is in a vacuum) takes out the alcohol and the aromas from the wine. They then attempt, as best they can, to separate the aromas and alcohol, keeping the former and adding as much as they can of this fraction back to the wine.

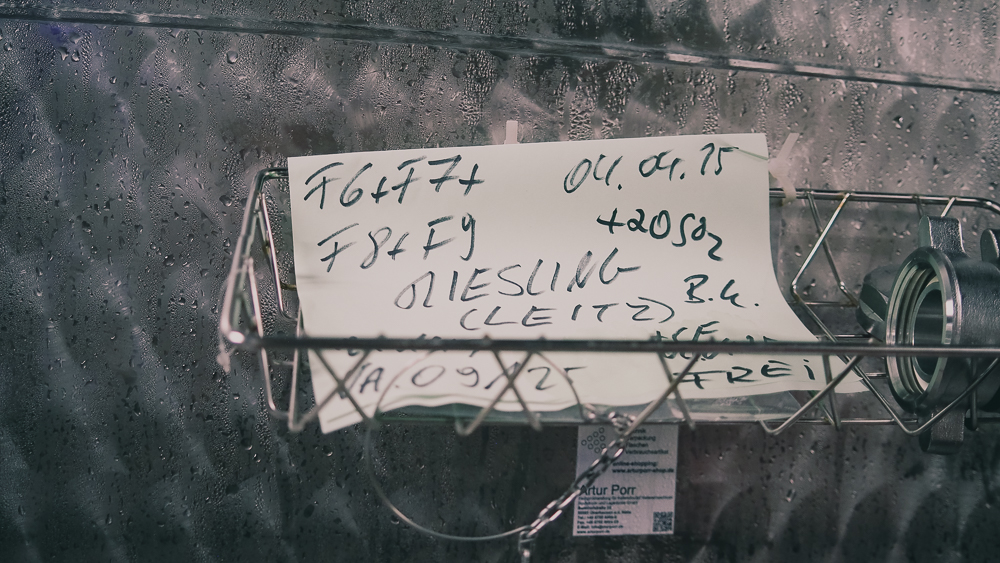

Bernhard Jung says that a lot of know-how is in the bottling. Sugar or grape must is added to the dealcoholized wine to make up for the lost alcohol. The resulting wine doesn’t taste particularly sweet, even with 40 g/litre of sugar. But it does mean that the wine must be sterilized before bottling, as it is microbiologically unstable. ‘We don’t want to pasteurize,’ he says. ‘We want cold sterile bottling, which is challenging.’ Using sulfites alone is not enough to protect the wine. Bernhard adds that if you want a good de-alcoholized product, then it’s best to start with a clean wine without too much acidity. This is because of the dilution effect: you need 1.2 litres to make a litre of de-alcoholized wine, so this boosts components like acidity that remain in the wine. ‘Muscat is a good example,’ he says, ‘but nobody wants it.’ They are focusing on Riesling, Chardonnay, Cabernet Sauvignon and Merlot, largely because of market demand. The wines they produce are in what he describes as the day-to-day drinking range. ‘I describe myself as a flex drinker,’ he says, sometimes drinking zero alcohol wine as well as regular wine.

Vacuum distillation and other techniques for alcohol removal explained

The vacuum distillation technique involves taking wine and fractionating it by running it over a column that gives it a large surface area to volume ratio in a vacuum, at a temperature of around 30–50 °C. This works in a similar way to a normal distillation column, but because of the vacuum it’s effective at much lower temperatures. First, some aromatic compounds are released together with some alcohol, and these are then captured to be added back to the wine (the limit here is how much can be added without raising the alcohol level too much). The next stage is to remove the rest of the alcohol from the wine, and this is metered because it is taxable (in Germany, it’s €13 per litre).

After this, the wine minus the alcohol and aromatics is reunited with some of its aromatics, and some additions are made (usually around 40 grams per litre of sugar) to make up for the lost mouthfeel caused by alcohol removal.

Critically, the wine must then be stabilized. One of the benefits of having alcohol in wine is that it helps prevent microbial growth. Take the alcohol away and add some sugar, and you have a time bomb on your hands. It’s essential for the wine to be sterilized, and this is usually achieved with filtration or pasteurization and some additions of sulfur dioxide. These wines are highly processed through necessity. If yeasts were to ferment to 40 g/l of residual sugar, they’d produce far more carbon dioxide than is made in the second fermentation of traditional method sparkling wine, and the bottles would literally be bombs.

Low temperature distillation may be the most widespread way of removing alcohol from wine, but there’s another technique that is also popular: the spinning cone. The cost of the equipment is higher than that for vacuum distillation, but some claim that it does a more precise job. It is a variation on the them of vacuum distillation, but rather than having a fixed area of filler in the column, in this process a series of cones rotate rapidly, and this centrifugal force turns the wine into a film. In the first step, nitrogen is introduced and a fraction is taken off that consists of the aromatic molecules plus some alcohol. Then the temperature is increased and the next fraction, which consists of mostly alcohol, is removed. The remaining dealcoholized wine is then recombined with some of the aromatic fraction before processing the low or no alcohol wine to make it stable.

A third technique involves using special membranes to separate different components of the wine, utilizing a form of filtration called cross-flow that works in a similar way to our kidneys. Here, the wine flows through filter columns tangentially to a membrane that has very fine pores, with water on the other side: normal filtration involves the wine being forced directly through a membrane, but this results in pores eventually clogging. With crossflow, also known as reverse osmosis, it’s possible to remove the alcohol, along with some water and organic acids, but leave all the other flavour components in the wine. The problem here is that it can’t get the alcohol levels low enough for the wine to be declared non-alcoholic.

The market for no-alcohol wine

There has been a lot of interest in no-alcohol wine, and it seems that this is a growing market. But just how big is it? A report from Grand View Research sizes the global non-alcoholic wine market size at USD 2.26 billion in 2023. This report predicts that the market will grow at a compounded growth rate of 7.9% from 2024 to 2030 to reach USD 3.78 billion. Sparkling wine currently makes up 60% of this market.

Fact.MR have published a report that is a little more bullish. They state that the market is USD 2.57 billion in 2024, will be worth USD 2.84 billion in 2025, and they predict it will grow by a CAGR of 10.4% and reach USD 7.64 billion by 2035.

Another market consultancy firm, the IWSR, have made their own predictions about the whole low and no alcohol category. Across 10 key markets, the combined no/low-alcohol market is expected to expand by +4% volume CAGR through 2028, with no-alcohol driving the majority of this growth, at +7% volume CAGR, while low-alcohol volumes remain broadly static. This includes other low and no products in addition to wine.

The rise in interest in non-alcoholic wine has been marked in the last year or two, but it’s important to remember that this still represents a small slice of the total wine market. Estimates are that it is currently between 0.35 and 1.5% of the market by volume, which is smaller than the market share of non-alcoholic beer (between 2 and 5%).

How does it taste, and what are the technical challenges?

From 2009-2011 I did some work for Tony Dann and his company TFC Wines around raising the profile of lower-alcohol ‘lighter’ wines, which TFC were specializing in. TFC was part of Conetech, the Californian company pioneering the spinning cone technology, and they’d encountered problems in selling their reduced alcohol wine Sovio in the UK because of EU regulations about what constituted wine. It was always interesting working for Dann, because he had strong opinions and was not afraid to express them forcefully in meetings.

I visited their facilities in California where I got to see the spinning cone in action, and tasted through many reduced alcohol wine products. One of the most interesting tastings involved looking at a series of samples of the same wine at different alcohol levels.

At the time, their interest was in lighter-style wines, not totally de-alcoholized wines, because they didn’t think it was possible to make commercially acceptable zero alcohol wine.

The idea was to start with a wine such as a Chardonnay at 14% alcohol. You take 10 000 litres, which you put through the spinning cone, taking off first the volatile fraction (‘essence’) and then the alcohol, leaving you with 8250 litres of Chardonnay at 4% alcohol. You then add the aromatic ‘essence’ back in, and the resulting 4% wine can be used as a blending component to add to untreated wine, to result in a final wine at a lower alcohol level

How did the wines taste? I started off looking at a Californian Chardonnay at 14.3% alcohol. It had a sweet, ripe, slightly buttery nose, leading to a rich buttery palate that was quite broad. I then tasted the same wine after it had been through the spinning cone column, at 4% alcohol. This was more minerally with tangerine notes and some spicy richness. The palate was lemony and tart with hollow fruit and an enhanced sensation of acidity. ‘Alcohol is a masking agent,’ said Conetech’s then head winemaker Scott Burr, ‘so taking it away reveals what’s there. It also adds sweetness to the palate.’ It’s this sweetness that is missing in the 4% sample, and which exaggerates the acidity.

The next wine was a blend of 10% of the 4% sample with the remainder of the original wine, resulting in a Chardonnay at 13.2%. This was fresher than the original with more acidity apparent. The fruit showed through more. There was quite a difference, and the 13.2% wine was much nicer than the 14.3% original.

Then I tried the alcohol fraction that comes off the machine. This had a big whiff of sulfur dioxide, which comes off with the alcohol, and tasted quite sweet with a nice richness to it. The next sample was the essence fraction: the aromatic component that’s the first to come off the column. This had lovely fruity aromatics when it was cut with water.

How does this service work with clients? ‘A smaller client might say they have a Zinfandel at 16.8% alcohol, so we do a run, take the 4% component and blend wines at a bunch of different alcohol levels,’ said Burr. ‘I don’t tell the client what the alcohol level should be.’ In terms of which wines are more successful, Burr says that it is not a curve, but instead there are sweet spots. ‘There are all kinds of different ones. The more oak the bigger the variance.’

I then tried four different Californian wines each at three alcohol levels: the original level, and then reduced levels of 11% and 8%. A Chardonnay that tasted sweet and buttery at 14% alcohol tasted fresher with nice definition at 11%, and then more lemony and refreshing at 8%. A rosé showed best at 12.2%, and was perhaps less successful at 8%. A Shiraz was sweet, juicy and spicy at 14.6%, but fresher and more vivid with less sweetness at 11%; at 8% it was more savoury with fresh, pure fruit and a more gastronomic character. A Merlot showed really well at 11% and fresh, juicy and bracing with more apparent acidity at 8%. These are inexpensive wines, but with this alcohol reduction they really showed very well.

What was immediately apparent was the role that alcohol has in shaping the flavour and aroma of the wine. Take just a little out, and you have a different wine. Remove it all, and you have something that really doesn’t taste all that wine like at all.

And this is the issue with zero alcohol wines. They may be interesting drinks in their own right, but none of them really taste like wine. There’s a hollowness to the palate and the aromas are just unusual, and not very wine-like. When you are served something in a bottle that looks just like regular wine, in a glass that you’d use for regular wine, and in a setting where you’d drink regular wine, you are expecting this drink to taste like wine. So there’s a psychological discordance here, and most people – even people who aren’t regular wine drinkers – do a double take on first sip. ‘What is this?’

The matrix effect: wine aroma isn’t just about aroma compounds

There are two reasons why it may prove impossible to create a convincing non-alcoholic wine that actually tastes like wine. One might be solvable with a lot of work; the second may not be solvable.

The first is that it’s not possible to neatly take off all the aroma compounds in one fraction, then take off the alcohol in a second, and then combine back the aroma compounds. This is because many of the desirable aroma compounds leave in the alcohol stream.

At the Australian Wine Research Institute’s Technical Conference in Adelaide in July 2025, Dr Wes Pearson did a seminar on the science of low alcohol wine. In his presentation he showed that when wine is dealcoholized in the spinning cone column most of the desirable aromas end up in the ethanol fraction, while most of the undesirables stay in the wine. They did and experiment to see whether they could get some of the desirables to stay by spiking their levels – they all left in the alcohol fraction, so this didn’t work.

The evidence in the scientific literature also shows that many of the interesting aroma compounds are lost in the dealcoholization process. Kumar and colleagues looked at the result of dealcoholizing wine by vacuum distillation using chemistry and also sensory analysis.[1] They showed that aroma compounds were reduced by 89-94% in dealcoholized wine. The study tracked 23 different aromatic components and the results were that in white wines just 10.6% were retained, in rosé 8.8% were retained and in reds just 6.3% were retained.

They found significant changes in acidity. For example, Total acidity (TA) showed a significant increase across all wine types (for example, in a white wine the original level was 6.88 g/L rising to 10.05 g/L in the dealcoholized wine), and pH lowers with this (for a white wine it lowered from 3.00 to 2.70). This is taking these parameters out of the normal range for table wines.

Another study[2] showed that dealcoholization by reverse osmosis (a membrane technique) did better in retaining aromas than vacuum distillation, but it wasn’t possible to get the dealcoholized wine below 0.5% alcohol, a regulatory requirement for no-alcohol wine, using this technique.

I quizzed Pearson about the extent of aroma loss with current technology. Is this taking into account the use of a first fractionation to separate out the aromatic fraction to later blend that back in?

‘Yes, this is the same process,’ he says. ‘Unless you are making a <0.05% alcohol product, this is what every producer would do. They would do a first pass of the wine through the spinning cone column that removes around 15% of the total ethanol in the wine. This dealcoholizes the starting wine to about 11-13% alcohol/volume depending on the initial concentration, and giving a distillate of around 55% ethanol and a large portion of the pretty estery compounds from the original wine. This is then put aside and a second pass is completed removing the remaining ethanol and that distillate is discarded. Then a small portion of the 55ish% ethanol is added back to the dealcoholized wine to get the final alcohol concentration to somewhere around 0.47%, or more generally <0.5%.’ The limitation on how much of the aromatic fraction can be returned to the wine is how high you want the final alcohol level to be. For non-alcoholic wine, the limit is 0.5%, so you can’t add all that much back.

‘Our spinning cone column here at the AWRI is a pilot plant, with an aroma recovery column that is filled with resin that is meant to extract the flavour compounds from the ethanol fraction once is has come out of the spinning cone column. Consequently, we only do one dealcoholisation pass. This aroma recovery column is in use in the EU commercially, but not here so far.’

Pearson adds, ‘commercially, with aroma recovery you’re still losing most of your volatiles. You can only add back a small amount.’

With much more work on technology, it may be possible to preserve more of the aroma molecules in the wine than is currently possible (see further on in this article where I discuss resin techniques for removing alcohol from the aroma fraction). But this won’t overcome the second, larger problem faced by non-alcoholic wines – the importance of the non-volatile matrix on aroma release.

Back in 2010 a group headed up by Vicente Ferreira came up with an interesting and counterintuitive result.[3] They took six wines of different styles, characterized the key aroma molecules of each, and then got rid of the aromas to leave what they titled the non-volatile wine matrix. They then added the wine aromas back, but by adding different aromas to different matrices. What they found is that if you add white wine aromas to red wine matrix, it smells more like a white wine. And vice versa. The authors state:

“Results have shown that the nonvolatile matrix of wine exerts a powerful effect on the perception of aroma, strong enough even to make a white wine aroma to smell as a red wine (increasing red, black, and dry fruit notes in detriment of white, yellow, citrus, and tropical) and vice versa and also to create differences in the aroma of reds. It has also been confirmed that the wine nonvolatile matrix exerts a powerful influence on the release of odorants.”

Further work by this group[4] has shown the importance, and also the complexity, of the non-volatile matrix on the aromas released by wine.

Alcohol is clearly playing an important part here, inhibiting the release of many molecules, but not all of them. Going back to the experiences I had at TFC, this explains why there are such marked differences in wines when even just a part of the alcohol is removed. There have been limited studies on wine aroma release at different alcohol levels, but it seems that once alcohol levels reach 10%, the release of some of the aromas is muted, and this increases with rising alcohol levels. So removing some alcohol is going to increase the release of many of the aromatic compounds, changing the nature of the wine. A review from 2017[5] looks at this, not just concerning wine, but also concerning spirits. It is well known that many whisky drinkers add a little water in order to release the aromas more.

Removing all the alcohol releases all of the aromatic compounds that are left, and this isn’t a good thing. Many of the good ones will have gone, and now the bad ones that were previously masked have taken centre stage.

Given these challenges, can we make more convincing alcohol-free wines? If so, how? To this end I spoke with a consultant who is a category expert, Irem Eren, who worked for several years with Bev Wizard, the company that TFC morphed into, and who now consults widely on the topic.

Irem Eren on reducing alcohol without removing all the aromas

How does she think we can deal with the two issues of aroma loss and also the hole that is left when the alcohol is removed?

‘With 0.5 and 0.0 alcohol wines, even though the alcohol level is only 0.5 difference, it makes a huge difference [to the wine],’ she says. ‘Even though there is this obsession with 0.0, I think the industry should get away from that and try to make a high quality product. If you can do it at 0.5, this is the key. The 0.5% alcohol is a kind of game changer, because it helps the aromas to carry more and it elongates the finish.

‘The best way at the moment to go down to 0.0 and separate the aromas is vacuum distillation,’ she says. ‘With this, depending on the technology that you use, you can separate three fractions, or two fractions. Regardless, what happens is that in the aroma fraction there is ethanol.’

‘With the spinning cone column the alcohol that is separated out goes up to 45% abv, but the aroma fraction has 35% abv. A technology called GoLo has three fractions. It separates the alcohol, the zero alcohol wine and the aromas. The alcohol comes out at 85% abv, but the aroma fraction has 65% abv. This means that because there is a significant amount of alcohol in the aroma fraction, you can only add back part of the aroma fraction. This is why many products have added aromas from flavour houses.’

A technology patented in 2016 looks very promising. The patent[6] was registered under the company name of Flavologic, but it’s now called Solos. First, a wine is dealcoholized. They use vacuum distillation, but they don’t solely on this – they say you can dealcoholize any way, but the key is their aroma recovery system, which is an add on process.

‘I think it’s a game changer,’ says Eren. ‘They don’t rely on the fraction of the aromas only, they separate two fractions. One is 0.0 and the other is ethanol plus aromas, the distillate. The distillate goes through a physical separation, not a chemical one. Is it a resin filtration.’

After this process, the alcohol level in the aroma fraction is reduced to 0.05%, so you can add it all back to the wine. ‘They can preserve 98% of the aromas,’ says Eren. She’d been working in the alcohol reduction field for 7 years, and was amazed by the results when she first tried them. ‘I said, this isn’t real. I thought it was added flavours.’

One producer that has been using Solos to good effect is Weingut Bergdolt-Reif & Nett in the Pfalz region of Germany. ‘Christian Nett started making dealcoholized wines,’ says Eren. ‘First he started with three wines, and now he has 12. For me, his Pinot Noir is a textbook Pfalz Pinot Noir. He also vinifies accordingly in order to get good results, and he uses this resin filtration to preserve the aromas. For me, it is the most winey product I have tasted.’ Nett also made a dealcoholized orange wine that Eren was impressed by.

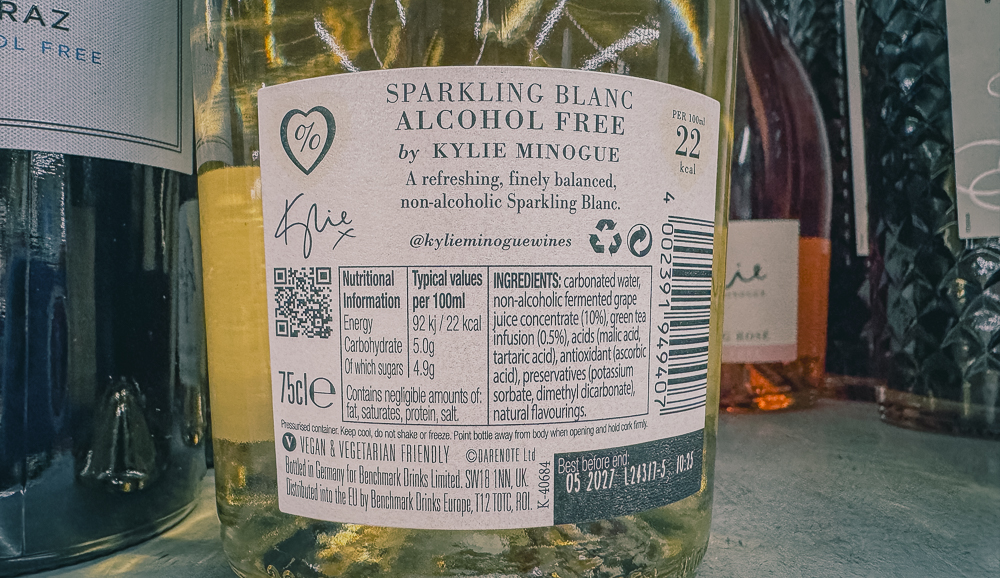

‘We have have been focusing too much on removing the alcohol, but as the category is growing I think the game changer will be the aroma recovery, if you want to make nonalcoholic wines similar to wine. Obviously there is another category of beverage style dealcoholized wines, like Kylie Minogue and Elton John.’

These are made in quite a different way, and aren’t legally wines. They aren’t dealcoholized, but instead are diluted grape juice (to reduce the total sugar level) or diluted grape juice concentrated fermented a bit with non-alcohol-producing microbes such as lactic acid bacteria to reduce the sugar a bit and then leave some sugar in the final ‘wine’. Carbon dioxide is then added to make them fizzy, as well as some flavourings.

Bolle take another approach, also using non-alcoholic fermentation. They start with a dealcoholized wine without recovering aroma, then do a second fermentation that doesn’t produce alcohol but which produces bubbles and some flavour.

‘Selecting the wine is very important, but the way you vinify is also important. When you de-alcoholized the acidity increases and the pH decreases. Many producers used sugar or rectified grape must to manage this. They used to use glycerol but this is not allowed any more. There are other things you can use such as mannoproteins or gum Arabic instead of relying on the sugar to create mouthfeel. Lees ageing and battonage also increases the mouthfeel.’

‘One of the keys is starting with a slightly lower acidity. The aroma recovery, enabling preservation of the aroma notes, is very important. But this [Solos] process is expensive and not all producers can afford this: it adds almost a Euro to the cost of the bottle.’

Adding bubbles, and the remarkable French Bloom Blanc de Blancs

80% of the alcohol-free market is for sparkling wine. The reason for this? Adding bubbles is one of the ways of replacing the effect of alcohol on the mouthfeel of the wine, according to Dr Matthias Schmitt, who I met at Geisenheim, where he researches low and no-alcohol wine, among other things. The other is adding sugar, and this really does work quite well, both in countering the high acid caused by the concentration effect (this means that the wines don’t taste as sweet as the analysis would suggest), and it also adds some volume to the palate.

One of the most ambitious of the sparkling projects is French Bloom. It’s the brainchild of Maggie and Rodolphe Frerejean-Taittinger (Rodolphe is the CEO of Champagne Frerejean Frères, based in Avize), together with Constance Jablonski, who is co-founder with Maggie. I met with Rodolphe and Maggie to taste these wines and came away impressed. So were Moët Hennessy, who bought a big slice of the business.

Together they set out on a quest to make complex alcohol-free wines. The beginning of the project was in 2020, when they started to dealcoholize wine. ‘One of the first learnings we had is that you can take the best wine in the world, and if you’re dealcoholizing it, it’s not going to make a good alcohol-free wine,’ says Rodolphe.

They have dealcoholized some great Champagnes and great Burgundies. ‘It’s almost blasphemy,’ jokes Maggie. Rodolphe continues: ‘If you take the best Puligny-Montrachet and dealcoholize it, you you’re losing the point because the backbone of the wine is gone. We realized that actually the skills and the knowhow from Cognac is perhaps the bigger inspiration for us to do what we need to do. In Cognac you take the base wines of Ugni Blanc, which are absolutely undrinkable before being distilled. But the profile of these wines is made to be distilled. So coming from that, you know, we realize that we have to create those base wines. We need to have base wines that have enough shoulder and body to be able to support the dealcoholization.’

‘The entire thesis we have is to create a base wine with more more body, more oxidative, more acidified, and more oaky, to support the dealcoholization. On top of that, the process is improving is improving is improving, and also the preservation of provenance is coming.’

‘We believe that great wine is first a great terroir in a bottle. The provenance aspect is really key. This is really where you go to the next generations of complex alcohol-free wine, which are much more than just a method, but also the signature of a terroir.’

‘The concept of base wine is something that we are really working on,’ he says. ‘So we have 30% base wine aged in barrels, blending together different years. We have a base wine with 30% of 2022 and 2023, aged in barrels, and then we mix it with the harvest of 2024. 70% of the of the wine is not aged in barrels. So the base wines are extremely, oxidative, extremely oaky and extremely acidified. So we use this really strong base wine to drill the aromatic profile of the wine and especially to get back some textures of the wine after the dealcoholizations. This is really important because most of the alcohol-free wines are very disappointing in terms of nose, in terms of body, in terms of texture, and in terms of length.’

‘So to get back this three-dimensional drawing, with the body, with the length, with the texture, we need to exaggerate the parameters.’ The base wine is dealcoholized in the southwest of France. It is then pressurized by adding carbon dioxide to 6 bars of pressure.

One interesting aspect is that they use voile (a yeast flor layer) on some of the barrels. This helps create base wines with personality, adding another level of complexity to the wine.

We taste the wines, and it feels weird not to be spitting! My initial impression is that they taste really good, in a way that most alcohol-free wines don’t. The wines have a vinous quality to them. ‘One of the problems alcohol-free wines often have is that they taste metallic,’ says Rodolphe. ‘There is a dealcoholized wine nose, too.’

‘What we’ve noticed is the less you do before,’ says Maggie, ‘the more you have to add afterwards.’ Nothing is added to this wine: it is dealcoholized, carbonated, then pasteurized. And this is only possible because they work as hard as possible at getting the base wine right.

La Cuvée is their first alcohol-free vintage Blanc de Blancs, and it’s from 2022. The grapes come from older vines from Limoux, with much lower yields and more concentration, and it is aged in barrel for 8 months in barrel without sulfites. The level of oxidation here is quite significant. One of the problems they had was the fact that this is a niche wine. They are trying to replicate the taste of an old Champagne that’s 30 or 40 years old.

‘What we’re trying to achieve is a wine that was very much reminiscent of the vintages that Rodolphe and I love that are 25 to 35 years old,’ says Maggie. ‘Hopefully, it’s already signalling that, with the beautiful coppery robe. We wanted to see what we were capable of achieving.’

French Bloom L’Extra Brut Blanc de Blancs NV

0% alcohol. This has really interesting aromas of nuts, apple and honey, and it’s slightly oxidative in a nice way. There’s real complexity and interest here. There’s a bit of apple crumble character on the palate, and the mid-palate has a slight hollowness from the lack of alcohol, but there’s also some richness here. Juicy and focused with nice acidity on the finish. The acid carries everything. Bold and layered with great complexity, this is really gastronomic. So encouraging to see this, which isn’t full of sugar. Just one calorie!

French Bloom Le Rosé NV

This is the tenth version of the rosé. Organic Chardonnay and Pinot Noir. This has a base of wine with some reserve wine, but aged in stainless steel. They take the dealcoholized base wine then add some Pinot Noir must, almost like a liqueur d’exposition, to compensate from the dealcoholized Chardonnay base. 38 g/l sugar level in the final wine. This is pure, bright and fruity with nice balance – it’s not too sweet, with beautiful red cherry and strawberry flavours, and some nice acidity (they add some organic lemon juice after the dealcoholization). Juicy and quite delicious with purity and precision. Just a hint of tea and rhubarb on the finish.

French Bloom La Cuvée Blanc de Blancs 2022

0% alcohol. They tried this a few times before they got it right. 100% aged in barrel for eight months without sulphites. From older Chardonnay vines on limestone, higher up. The aim is to replicate the taste of a 30 year old Champagne. This is gold with some brown hints, and it’s aromatically really powerful with apple, nuts, honey and spice. Oxidative and complex. In the mouth there’s tarte tatin, apricot, roast almond, honey and some nice spicy detail. There’s some very old Champagne/Calvados character and it’s very complex, with lovely depth.

How close to normal wine does alcohol-free wine have to taste?

So we have got to the stage where it looks like short of the wine fairy mentioned at the beginning of the article, we aren’t going to have alcohol-free versions of the famous (and not so famous) wines that we know and love.

But what we have here, despite the challenges in making truly wine-like alcohol-free wines, is a growing category. There are some good products out there. I’ve tried quite a few. The issue is that they are almost all very obviously not wine-like.

So there’s a question. How wine-like do we need our alcohol-free wines to be? The answer will vary by customer. For some, the current products are good enough. My prediction, though, is that for a large segment of the wine-drinking population, the lack of wine-like qualities will prove a barrier to uptake.

But we need to remember, wine isn’t just about the flavour of the liquid in the glass. It is a perceptual object where flavour is a very important part of the package, but not its entirety. The context, the bottle, the glass, the act of pouring from the bottle, the accompaniment to a meal – all of these are things that are associated with wine, and which become part of that perceptual object. Some people can over-ride the double-take on first sip – the discordance that the lack of wine-like flavour causes – and carry on drinking as if it were wine, and find this experience satisfactory.

Will the challenges and costs associated with making de-alcoholized wines lead to more products packaged like wine, with visual cues associated with wine, begin to appear on the market? For example, the Benchmark Drinks Sparkling Blanc by Kylie Minogue looks just like a wine, but is made in Germany from grape juice concentrate, acids and some flavourants such as tea. The same company make an Elton John fizz using similar techniques, including partial fermentation with non-alcohol producing microbes (I’m assuming lactic acid bacteria). This manufacturing process means that the ‘wines’ can be on the shelf at low prices, and everyone makes some money. More than 1 million bottles of the Kylie product have been sold in the UK.

And then, of course, we have drinks designed to do the job of wine at the table, but which aren’t pretending to be wine. Good examples of this would be sparkling teas (Saicho, for example, make a range of these, and upmarket department store Fortnum & Mason have their own brand sparkling tea that is selling very well) and the Muri drinks from Denmark are complex and impressive.

It’s an interesting space to work in, and for now de-alcoholized wine looks set to stay in the everyday drinking category, with the exception of some of the sparkling products. Removing alcohol causes so many changes to a wine that some creativity is needed to make something compelling and wine like. My prediction is that the big growth opportunity lies in creating wines from ground up that have never had an alcoholic fermentation. The fact that they cannot be labelled as wine shouldn’t hold them back: the packaging cues and the shelf space next to wine are enough to tell people that these are drinks without alcohol that do the same job as wine.

[1] Kumar Y, Italiano L, Schmitt L et al 2025 Dealcoholization of wine by vacuum distillation: Volatile and non-volatile profile, and sensory analysis. Food Chemistry 495:146499

[2] Sam FE, Ma T, Liang Y et al 2021 Comparison between membrane and thermal Dealcoholization methods: Their impact on the chemical parameters, volatile composition, and sensory characteristics of wines. Membranes 11:957

[3] Sáenz-Navajas MP, Campo E, Culleré L, Fernández-Zurbano P, Valentin D, Ferreira V 2010 Effects of the nonvolatile matrix on the aroma perception of wine. Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry 58:5574-5585

[4] Lopez R, Wen Y, Ferreira V 2024 The remarkable effects of the non-volatile matrix of wine on the release of volatile compounds evaluated by analysing their release to the headspaces (No. ART-2024-139507)

[5] Ickes CM, Cadwallader KR 2017 Effects of ethanol on flavor perception in alcoholic beverages. Chemosensory Perception 104:119-134

[6] https://patents.google.com/patent/DE102015119154A1/en?assignee=flavologic&oq=flavologic