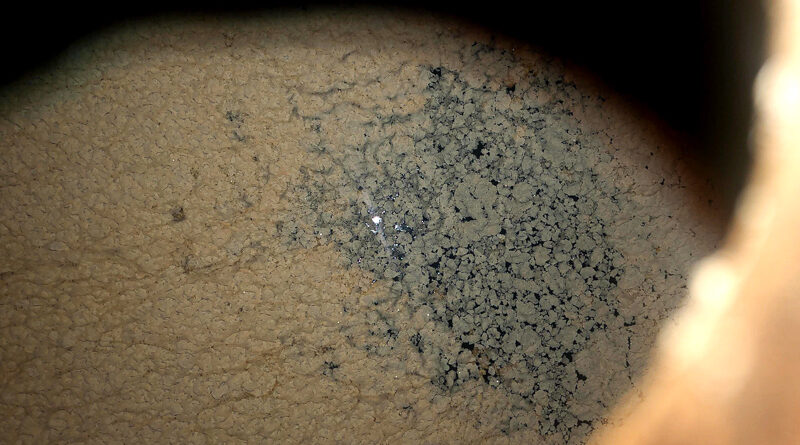

The science of flor: what’s that growing on my wine?

What is flor? It’s something that grows on the surface of wine: a film of yeasts. And it alters the flavour of the wine in interesting ways. Currently in fashion, it’s a subject that’s worth finding out about.

We can only speculate about how the effects of flor were first discovered. Perhaps somebody left a barrel incompletely filled. The air in the headspace at the top of that barrel contains oxygen which would have interacted with the wine. And before long, a thin film of what looked like mould would have grown on its surface. This would have been rather an alarming development. Perhaps the mould might have been growing quite a while before it was detected, and the winemaker – scared that the wine might have gone bad – may then have tasted the wine with trepidation. It must have been a great relief for them to find a wine that instead of being ruined was fresh, and had some really interesting characteristics: a salty tangy bite, lovely savouriness, and no signs of oxidation at all.

Two wine regions have become famous for flor. The first is Jerez in Spain’s Andalucia region, where the biologically aged sherries Fino and Manzanilla develop under flor. A third style, Amontillado starts its life under flor then develops oxidatively afterwards. The second is France’s Jura region, where Vin Jaune also develops this way. There are other places with a tradition with flor-aged wines, but they are less well known. There now seems to be much wider interest in making wines this way, even where it was never a local tradition. This is part of the general opening of minds in the world of wine that has also seen the return of clay (amphorae, tinajas, talhas and qvevri) and a burgeoning interest in making wines naturally.

I remember well my first visit to Jerez. To experience a major wine region for the first time is always memorable. Also, what I’d learned in books – that Palomino is an essentially neutral grape variety and that the vineyards here are all the same – was shaken up by what I saw on that visit. A return trip a few years later further convinced me that the future for this region involves a return to the vineyards, and turning back the clock 50 years or more to before the expansion of vineyard area and the creation of ‘big Sherry’. A careful reading of the history books shows that in the past, the best Finos and Manzanillas weren’t fortified at all. And now there are a small band of producers who are making unfortified biologically aged wines that are quite stunning. Of all the wines in the region, it is those biological Sherries, aged under flor, that are the most compelling wines to me.

All sherry starts out as a dry white wine known as ‘mosto’. In the old days, when all sherry was fermented in barrels, the classification of wines would have been an immense task; these days, most is fermented in much larger stainless steel tanks, and so it makes life for the cellar master a lot easier. Generally speaking, the lighter, more delicate wines from the best pagos (vineyards) are chosen for biological ageing, and they are put into barrels that are deliberately only 80% filled, in order for the layer of flor to grow at the interface between the air and the wine. Most of these wines are fortified to around 15.4% alcohol, which is close to the limit for flor growth, but any lower and less desirable microbes might be encouraged to grow with the attendant risk of spoilage. Wines for oxidative ageing are fortified to 18% alcohol, so nothing can grow in them. But there are some producers who are going back to the old method of drying the Palomino grapes for a day or so on small mats, called asoleo, to raise the sugar levels so that no fortification is needed.

Technically, the flor (or ‘velum’ as it is also known) is a biofilm made up of the yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae. This is the same species of yeast that carries out alcoholic fermentation, but it is a specially adapted version that is able to cope with the rather hostile conditions found in a sherry cask. The challenges facing the yeast are quite extreme: the wine in cask is quite acidic, has high alcohol, very little sugar, and there is also usually around 30 mg/litre of sulfur dioxide present. But the flor yeast has adapted its cell wall so that it floats and is able to form a surface film where it is able to access the oxygen needed to metabolise the alternative carbon sources of alcohol and glycerol. It also has efficient antioxidant defences to cope with the increased oxidative stress this lifestyle brings.

How does the flor affect wine flavour? If the layer is thick enough, it protects the developing wine from the air present in the top of the barrel, which means that unlike an oloroso, which turns brown, the sherry under this layer stays fresh and pale in colour. As the yeast feeds off alcohol, it produces acetaldehyde, which has flavours of nuts and apples, and in this process the alcohol level of the sherry is reduced by around 0.2-0.3% a year. Acetaldehyde levels in a Fino or Manzanilla are typically around 300-400 mg/litre, but can be as high as 800. Glycerol, another important wine component, is also consumed by the yeasts, and dips from a starting level of around 7 g/litre down to around 0.3 g/litre, which changes the mouthfeel, making the wine feel less viscous and fresher and lighter. There’s also an increase in the levels of a compound called sotolon, which adds spicy, curry nut notes.

Two factors help increase the thickness of the flor layer. The first is the way that sherry is made in the solera system: new wine is being introduced into each barrel at various stages, using a special ‘canoe’ device that doesn’t disrupt the flor, and this brings with it fresh nutrients to keep the yeast cells growing healthily. The second is the cellar environment: cooler, more humid conditions make for a thicker flor layer. Consequently, the coastal towns of Sanlúcar de Barrameda and El Puerto de Santa Maria tend to have higher levels of flor, and there are also seasonal changes with thicker flor in spring and autumn. Should the flor struggle or die, then the sherry can be fortified further to 17or 18% alcohol, and then it begins its second, oxidative journey. This is then an amontillado.

How does flor affect flavour? I find it adds a distinctive tangy quality. There’s some saltiness, too, and a lovely savoury edge. The acetaldehyde tends to add some appley character, which you’d normally associate with oxidation, but in the context of a fresh, zippy white seems to work. Flor character is a bit like oak, in that it can be overdone. Some is good, but that doesn’t mean more is better.

Microbes make wine, but usually after fermentation (and malolactic fermentation) their job is over. The wonderful thing about flor-aged wines is that the microbes are involved all the way.

Whether or not flor appears is still a bit mysterious. If you are working in a region where it isn’t traditional, often the first flor-aged wines are made as a sort of accident: a flor layer appears on the wine and then the winemaker decides to take a risk and let it carry on growing. It’s becoming a legitimate style choice, which I think is a wonderful thing. Few have the courage to leave the wine under flor for as long as happens in Jerez or the Jura, but I’ve still had some impressive examples. In the future, it will be exciting to see more unfortified flor-aged wines coming from Jerez: the rules have recently changed so that it’s now legal to call unfortified wines from the region Sherry, in a return to the past.

Picture credits: title picture is mine, through the bunghole of a Fino Sherry cask in Jerez. The other two are courtesy Silwervis.