Modernity meets tradition in Rioja: interviewing Victor Urrutia of CVNE

A wine region born of industry and necessity – just a few hour’s drive from Bordeaux – Rioja was the place Bordeaux turned to for grapes when phylloxera hit. This is not a region with a grand aristocratic history, but one born of an urgent need for supply. In the late 1800s wine was transported by train in bulk to France and this symbiotic relationship heavily influenced winemaking in the region. France dictated its requirements and Rioja delivered. A cross fertilisation of knowledge and production techniques occurred that is still in evidence today.

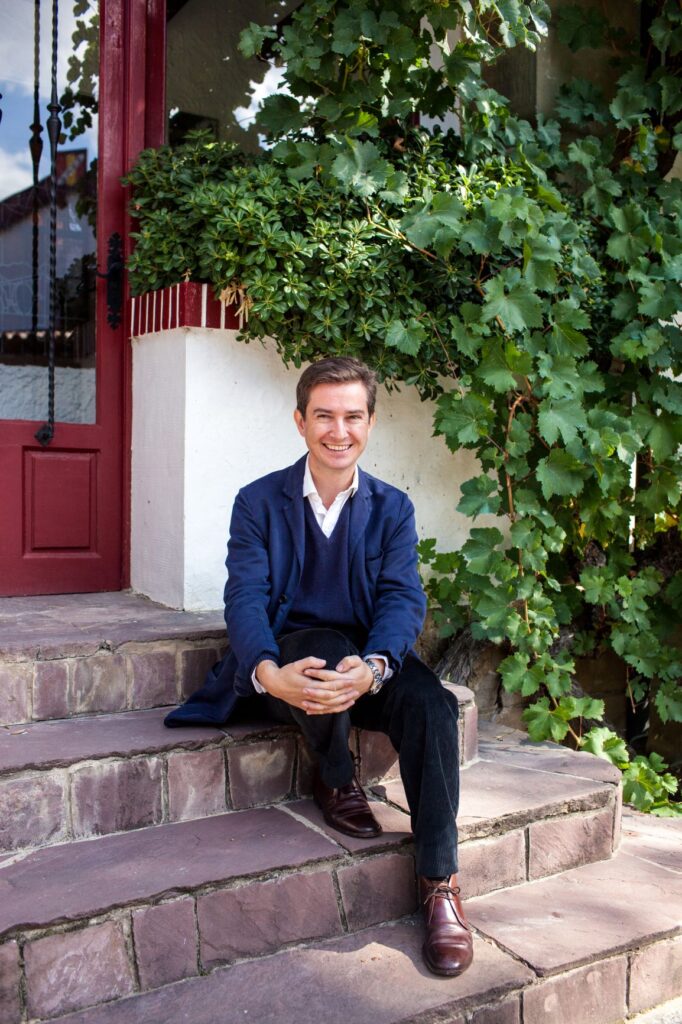

Lisse Garnett examines the region through the eyes of Victor Urrutia, CEO of CVNE, founded by two enterprising brothers in 1879 and which includes the Imperial, Viña Real and Contino wineries. Both Lisse’s and Jamie Goode’s tasting notes follow.

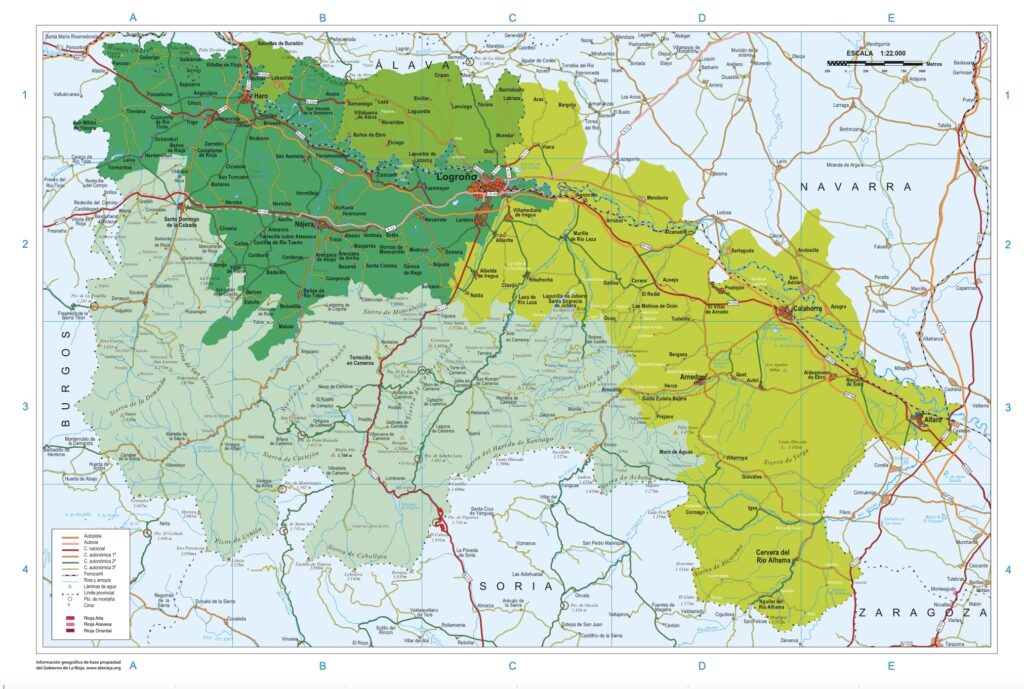

Rioja lies in the very north of Spain bordering the Basque country and is a region defined by geography rather than politics. The climate is continental and heavily influenced by the Ebro River as well as the Cantabrian mountain range that separates it from the Basque region. This natural barrier creates a particular microclimate that mitigates rainfall and makes for a long, dry ripening period. The soil here is typically calcareous and drains well, allowing for deep root penetration and drought resistance. Rioja is the home of Tempranillo, an early ripening grape that carries over thirty different names in Spain alone. This grape finds its greatest expression in the hills of Rioja and Ribera del Duero. The Romans grew grapes here too, but the area took off as a wine region in the 1850s when first downy mildew then phylloxera hit France. Later a railway was built to Bordeaux and Haro became the second city in Spain to get electricity. These modern advancements served the growing wine industry well.

Bordeaux’s need when phylloxera hit was extreme. Wine was transported by train in bulk. At certain points in the late 19th century over 13 million gallons of wine was crossing the border from Rioja monthly. The French tutored the Spanish in oak ageing, and perhaps because American oak was cheaper it became a defining characteristic of the reds, French oak was and is also used. Blending too became a trademark – Tempranillo plus Garnacha to balance the alcohol and Mazeulo (Carignan) for the reds, much like Cabernet Sauvignon, Merlot and Cabernet Franc in Bordeaux.

Rioja also makes some incredibly high quality whites that are suitable for ageing. Usually made from Garnacha Blanca, Macabeo (Viura) and Malvasia, these wines were so unpopular in the 90s that many ceased to be produced. This is true of the Monopole Clásico Blanco Seco Gran Reserva we tasted which began production in 1915 but was simply discontinued when demand dried up. Reintroduced in 2014, we taste the just released 2015.

Rioja is made up of three regions, Rioja Alta, Rioja Baja (aka Rioja Oriental) and Rioja Alavesa. Alta, the highest, is known for bringing freshness, acidity and ageing potential. Rioja Alavesa offers structure and acid too and is more varied with the best grapes hailing from the poorest soils. Rioja Baja is known for rich alcoholic Grenache and is principally used for young wines and blending with Tempranillo. Barrel maturation and minimum ageing requirements are strictly enforced for Crianza, Reserva and Gran Reserva wines. Five red and nine white varieties are permitted. The most widely planted is Tempranillo.

CVNE is a company that falls into the ‘traditional’ Rioja camp with the other well established traditional brands, López de Heredia, Marqués de Murrieta and others such as La Rioja Alta. Much can be said of the schism between new wave and traditional in Rioja but even the terminology is subjective. Today’s traditional is the new modern and notions of what constitutes traditional and modern are as susceptible to fashion as wine tastes. Rioja has seen its popularity nose-dive in the past. Today, low-intervention winemaking and sustainability run in parallel with the way traditional wineries have pretty much always operated anyway. There has been a call in Rioja by some modern growers, to end blending and move toward what they describe as more terroir focused wines and single vineyard wines are definitely on the increase.

Lisse Garnett interviews Victor Urrutia, CEO of CVNE

LG/Where is your biggest market today?

VU/Our biggest market is in Spain – we have a loyal customer base, older people tend to be loyal to a brand in Spain and drink the same brand for life. The US is a big market too which is great for us, its a cool thing, they are open to doing new things. Wine tourism is also taking off in Rioja and that brings greater market potential yet twenty years ago there was no interest, it was not sexy at all.

LG/ Was it seen as fusty old man wine?

VU/At best! People didn’t care about it at all. There was simply no interest.

LG/Do you think there is a clear distinction today between the new wave Rioja producers and the more traditional?

VU/There has been much debate about that. I actually think that the differences between good producers are not that big. We had a big debate in the 90s about modernizing and that was really polarising because you had traditional producers such as ourselves, López de Heredia and three of our neighbours, then you had the new producers like Roda and Sierra Cantabria and in those days the differences were huge, they were all about concentration – alcoholic wines released very young with double barrel ageing.

LG/As in market Ready?

VU/Well market ready I would argue is common to both but certainly released very young, a massive amount of new French oak versus us releasing our Grand Reservas way down the road, lighter in style. In those days the debate was huge and we were completely unfashionable.

But if you taste some of those wines now, the better new wave wines from the 90s compared to some of our Gran Reservas, they are not completely different.

I think over time they do converge a bit, the good ones. I think time is a good leveller of things and especially in this debate it does narrow the focus. The interesting thing is that those wines from the 90s that were so fashionable, I hate to say this, but they are not as fashionable now as they were then.

Tastes have changed and there is a new breed of producers whom I like very much and their focus is less on concentration and extraction more on a precise definition of the vineyard. In that sense they have much more in common with us.

LG/Because you have always been terroir driven? Although you use assemblage and for some purists that is a dirty word?

VU/We were always terroir driven but with a catch in the sense that we always blend a lot too. We don’t so much blend from different vintages but we do blend from different plots for a particular wine. Our Imperial does not come from the same vineyard, it’s a blend of different vineyards, it’s always the same vineyards but it’s not always the same proportions. There are three different villages and in all perhaps about 18 different plots.

LG/And you have a particular microclimate?

That’s the thing about Rioja, it’s just so scenic and you can see the Sierra there. In the Basque country on the other side where it rains a lot and it’s like England, the clouds get stuck there and we benefit and the river runs through, we benefit from this near Atlantic influence.

LG/Can you detect terroir in your wines?

We all have our style, Rioja Alta is so easy to detect because it’s just so distinctive. On the one hand you have the traditionalists, – the Rioja Alta with the more oaky side to it, Tondonia wines are thinner and more vinous, ours are more chunky, more structured. I often like these wines when they are young and they still have the sweetness of the fruit. Yet people in the know will tell you that if it’s a good Gran Reserva from Rioja wait forty years.

LG/And I understand you have wines dating right back to 1888 in your cellar, do you plan to release them?

We do taste old vintages and in the past nobody wanted them but we sold a bit in the US and then stopped because I could see that people wanted everything, they wanted all of it and the reason we have these wines is because of my forefathers – they were amazing people because they didn’t seem to care about selling the wine hahaha, if it wasn’t sold they just left it there, a sort of anti-business model. I think they had the most amazing lives they did whatever they wanted, they didn’t have modern corporate culture, they weren’t too fussed about profit or turnaround.

LG/ How do you feel about the cult value of Lopez de Heredia Viña Tondonia Gran Reserva Rosado, which was supposed to be a cheap wine and has sold out everywhere – if you can get it it costs way over a hundred pounds?

VU/I think that’s brilliant, it’s not for everyone, its aged in old barrels, vinous. Today people just want special things that are true and authentic, they don’t want something just because its expensive. They want something distinctive and the Tondonia rosé is unique.

We do roses but we do a Contina rosé which is a different style, it’s a light red really, it’s a Graciano and Grenache blend. Whites are more our thing in terms of originality. A lot of makers stopped making their distinctive whites because they simply were not selling them. Tondonia did that and so did we, we stopped making Monopole Clásico because we simply were not selling it, no one wanted to buy it.

People in Spain were not that into white wine, it had a terrible reputation, we actually have a saying ‘the best white is a red’. Its a stupid thing to say but I think because fish was an important dish and they would drink it with a red Gran Reserva. Today young people and I – will drink an Albariño and a good fish is probably going to be a lot better with a white than a red regardless! It makes more sense.

LG/ What is it that makes this white, the Monopole Clásico Gran Reserva unique aside from the incredible retro label and the use of the original bottle shape?

VU/ We do it in a sherry style, a Manzanilla sherry style. We make the wines in a traditional way; it ferments in concrete and then we move it into butts and barrels where it stays for 5 years. We do 5 barrels in total so tiny amounts. We just released the 14 and now we are on the 15. The idea is to do it every year but we only brought it back a few years ago and we make a tiny amount from extremely low yielding Viura grown at altitude.

LG/Palomino is experiencing a renaissance period, do you rate its potential?

VU/Palomino is fascinating, you might argue it’s the terroir grape because it expresses what’s there. It so neutral but also because they are worked so much in the winery that it becomes a winery wine but that’s not necessarily a bad thing. As a huge fan of sherry, I don’t think that should give a wine a bad reputation.

LG/Have you changed the way you work, modernised in any way?

VU/Not really, small concessions related to technology perhaps in harvesting. When we harvest we use large plastic cases to transport the fruit whereas in the past we would have used thin narrow wooden containers but the plastic ones are wider and the fruit doesn’t get crushed as much, they have aeration, you can transport them on the back of the truck and they are better for the fruit so when that is the case it’s hard to argue against it. Being a luddite for luddite’s sake doesn’t make sense. So yes you are a traditionalist but also an early stage industrialist.

LG/ How sustainable are you?

VU/Sustainability is big in Spain and in Rioja it’s easier to be organic. Low rainfall makes it easier. We consume too much. For every bottle of wine 4 litres of water is consumed, for the last twenty years we’ve had our own water waste management facility to limit water wastage and in terms of CO2, we are trying to make parity between what we consume and what we emit.

LG/You have the benefit of years of experience. How does this intergenerational knowledge get passed down?

VU/Well I’m the 5th generation at Cvne and we’ve had FIVE winemakers in 140 years, that’s IT! Maria started there in her twenties and she’d been there 30 years now. We have many women working for us but that’s not positive discrimination we simply choose the best person for the job. The person in charge, Irene is a doctor, she’s young, tall, strong, you have to be. Interestingly as an aside Cvne is a feminine word, La Cvne. We brought back winemaker Ezequiel García who was here for 30 years, to remake the Monopole.

We also have the same people, a few families, who have come every year from the South of Spain to pick since the 70s.

LG/What’s it like being part of an old family in Spain, does it bring status? Are you hugely respected as old families seem to be in Italy?

VU/The South of Spain and Italy have a lot more in common in that sense in terms of being very structured in a class way, big properties belonging to two families and not that many people and it’s not a model I particularly like but it certainly was the case in Italy from Milan downwards and in Spain from Madrid down but not so much where we are based in Rioja, our model is more industrial in that sense. The class thing, at least in the North, doesn’t exist as much, people don’t use Usted – (the formal you). Everyone is on first name terms in the wine business – the business structure is much flatter.

LG/Yes these were farms that were created to serve a market in Bordeaux.

VU/Exactly, we had phylloxera and really the people who founded these wineries were business people, entrepreneurs who saw an opportunity. You might compare us to Sherry where everyone is known including the families. But actually in our case its more subtle and discreet and not like that at all. Our name is not associated with the winery in anyway and it has been like that since the beginning. Most people do want to show off about these things but we don’t really want to do that at all. Maybe it’s a Basque thing. My family is Basque and perhaps more introverted, more about industry than show. Luckily for us in Spain we didn’t have a reputation so people don’t really know us. Anonymity is a beautiful thing.

LG/Why is Prosecco so much more popular than Cava? For me Cava is a more consistent product, though there are some ghastly ones and it’s also reasonable in terms of price.

VU/Because Italians are so good at marketing and we are so terrible. Because we are terrible salespeople, that’s a fact, Italians are brilliant at it and a lot of people in Spain have this complex about selling Spain. Italy is a proud nation, goods are marketed with an Italian flag or made in Italy, the Vespa, the Ferrari – the imagery is very strong and very compelling whereas there aren’t that many Spanish brands are there? There’s no cars, there’s no fashion.

LG/ There seems to be this incredible humility in Spain. I always wonder how you put up with us English..

VU/ Spanish people are incredibly hospitable but here’s the thing, most people in Spain because of our chequered history politically they just don’t care too much for Spain. You will see that with many of my contemporaries when they talk about their wine, they will talk about themselves, the vineyards, the village, the larger region but they don’t have much of a thought for Spain itself and we actually do the opposite. Our symbol is the Spanish flag and we are quite proud of that. There’s actually no companies in Spain that have the Spanish flag as their symbol which is silly, if you think of the Union Jack or the American flag. There is us and Iberia, the airline, which now belongs to Britain and they used to have the Spanish flag but they took that away which I thought was a silly thing to do, perhaps they thought it was old fashioned.

THE WINES

JG/Cvne Monopole Clásico Blanco Seco Gran Reserva 2015 Rioja, Spain 13.5% alcohol. Full yellow colour. Intense nose of woodspice, cedar, honey and apples as well as some lime. The palate is intense and rich but has freshness still, with just a hint of oiliness and some powerful spicy lime, as well as hints of fino sherry, wax and marzipan. A full, complete white wine that’s quite profound. 95/100

JG/Cune Imperial Gran Reserva 2015 Rioja, Spain 14% alcohol. This is powerful, quite traditional, but refined. There’s a lot of fruit here, mainly cherries and blackberries, but also a spicy savouriness and some vanilla oak under the wall of fruit. Ripe and rich, but also with a savoury dimension, and should age beautifully. 94/100

LG/Cvne Monopole Clásico Blanco Seco Gran Reserva 2015 Rioja, Spain 13.5% alcohol. This deliciously dry salty viscous camomile-scented nutty vanilla buttercream spiced textural dream is very much to my taste. Waxy and fruity, savoury, oily like lanolin and with those gorgeous nutty, briny, flor tinged Manzanilla flavours: almonds, apricots, lemons. Mouthwateringly tangy and fantastically complex. The most delicious white wine I have tasted this year. 95

LG/Cune Imperial Gran Reserva 2015 Rioja, Spain 14% alcohol – at least 5 years before release and two and a half in barrel. Black pepper from the Tempranillo (a typical characteristic in Rioja), red fruit, cinnamon. Delicious savoury rich dark black cherry and vanilla, with gorgeous silky tannins and a touch of liquorice (I tasted this when it had been open for 24hours) 94

Gran Reservas are becoming increasingly rare, they have to be aged for extended periods (at least two years in oak) and require considerable outlay in terms of storage and delayed profit. Crianza and Reserva must spend at least a year in oak.