Who is Charlie Herring? The story behind the remarkable wines and ciders of Tim Phillips

By Lisse Garnett and Jamie Goode

Website: http://www.charlieherring.com/

We first met the son of the man that birthed Charlie at the wine world equivalent of a modern-day literary salon. A sumptuous authentic rustic feast had been catered for our small yet knowledgeable group. The rich aroma of Calderada aroused our senses as we entered a well-heeled west London garden, each clutching our vinous treasures in conceited hope of trumping our peers. It was a warm fragrant summer day, dappled in sunlight – there we were, shaded by limes and beautifully furnished with fruit de mer and the finest wines known to humanity.

Our intimidating patroness held court over this coterie of quivering male minions who proffered ever more impressive bottles for her pleasure. Grateful for the chance to shine, we vintage supplicants produced ever more impressive bottles, Didier Dagueneau Pouilly Fumé Silex 2009, Méo Camuzet Richebourg 1990 and on it went. Yet the star turn by far was a hand illustrated crown-capped bottle of homemade Hampshire cider, supplied by a scruffy capped t-shirt-wearing son of a vicar named Tim Phillips. First he arrested our palates and then he conquered our senses with his talk of nattering trees, wild ferment, farming ‘in nature’ and symbiotic woodland creatures.

This enlightened man was completely immune to our silly wine sparring, armed as he was with the labels his young daughter had hand drawn, the support of a loving wife and the magical secret walled garden he’d bought in Lymington Hampshire back in 2009 for £82 000.

Tim named his whole operation after a fictional character his inspirational father had invented when he was a child. His father was a wine collecting vicar with radical Bhuddist leanings, a habit of housing the homeless in the parish church and a thirst for La Tache. He was also an amateur cartoonist who signed his doodles, Charlie Herring.

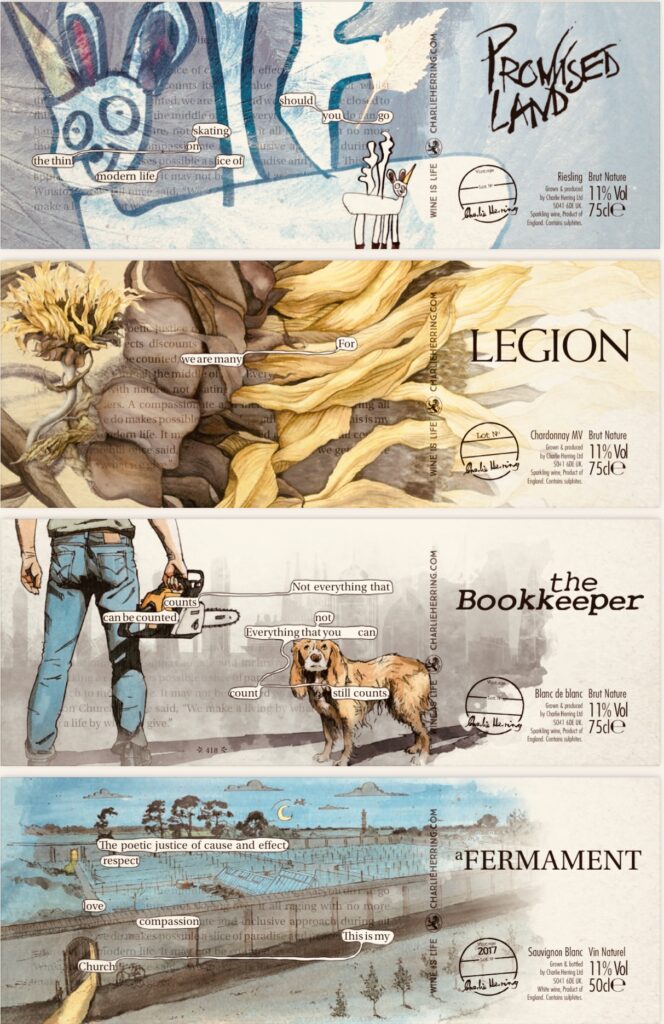

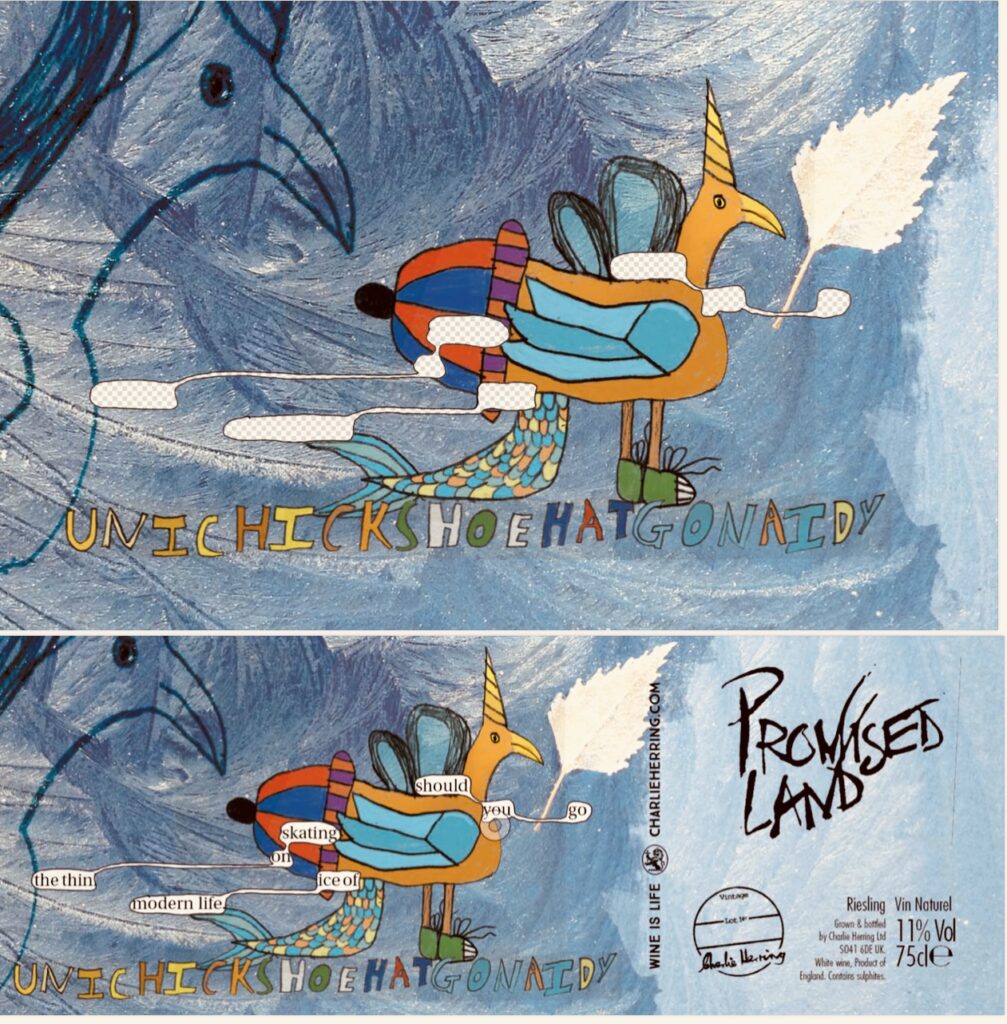

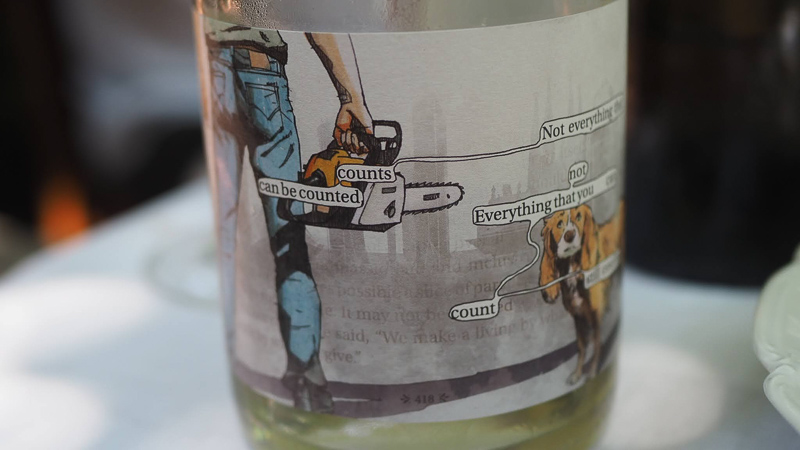

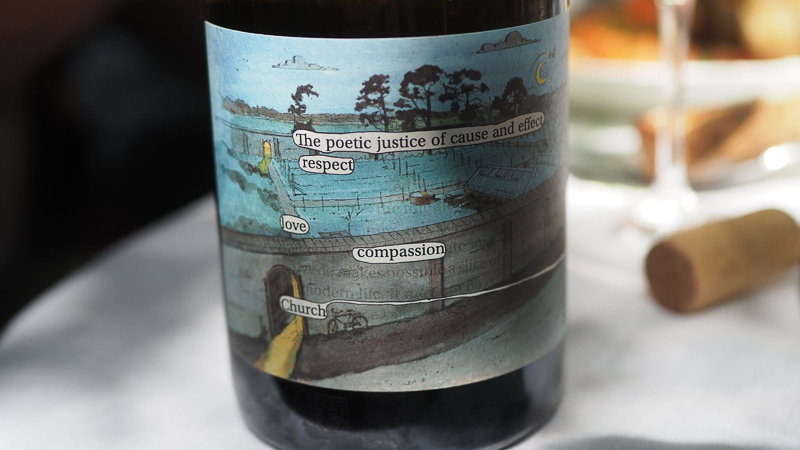

The six labels are all based on artwork by Tom Phillips – a Hampshire writer who metamorphosed an existing book named, A Human Document by W.H. Mallock in the 1960s . He took the entire volume and illustrated every page transforming it into a new work entitled, A Humument. You might very well see this as a metaphor for Tims work too.

Today Tim Phillips also owns a paddock, which is gradually metamorphosing into woodland. It is set far back from all else and much like the walled garden, thrumming with insects and life. Tim believes in nature. This beautiful but modest woodland will eventually provide 70% of his cider fruit and yet he has no plans for a classic orchard. When asked by commercial growers about his tonnage, he told us he answered:

‘Mate you might have your commercial orchard in Kent where they are packed in like this and you are spraying them cheek to jowl and you are struggling to find labour to pick these things and you are talking tonnage – What do you get for them? £70 a ton.’

‘A ton of apples for me is about 12 thousand pounds in cider and it costs me a pound to get it into the bottle with a label and a cap. ‘I’ve got the whole of nature looking after everything for me.’

The next time Lisse met Tim was at the Real Wine Fair where he spoke brilliantly at her Natural Wine Seminar. Mobbed by fans as he poured his beautiful Riesling, Lisse manned the stand for a moment so he might look about.

Finally Jamie and Lisse visited Lymington last month. The weather was warm and balmy and the location lovely. Tim’s paddock is called Yaldhurst though is not signposted, it sits at the end of a long drive marked by a gatehouse, the former lodge for a neighbouring mansion.

We walked from the other side of Lymington, about an hour away, as we walked up the drive we heard Tim’s neighbour belting out a tune. The approach lane is peppered with fifties homesteads. Tim’s ‘winery’ is housed in a small barn here and there is a shipping container he will one day use as his office. He also owns half of a modest structure onsite – a holiday cottage that he intends to covert into a home for his family. His wife is rightfully sceptical about its size but Tim is a man who sets his mind to something and then delivers.

He led us around his paddock which he has largely left to seed and we marvelled at its beauty. There are a number of young oak trees courtesy of resident jays’ acorns stores, a pretty pond, two yews, rich grasses, sculptural circular rotting wood circles for beetles, a single Cyprus, hedges and a few cider apple and perry pear trees. Areas of flattened grass are evidence of sleepy roe deer, everywhere are birds, butterflies and pretty wildflowers. This is farming Charlie Herring style. As the field has regenerated, he has been planting apple trees at 7 m spacing, in the midst of all the other growth. Eventually he will have 70 trees, each of which will yield between 20 and 100 kg of apples a year. There are also some more mature woods here and he is actively managing them with coppicing, which greatly expands the life of the trees, is better for biodiversity, and yields something useful each year.

‘I do everything on my own,’ says Tim, ‘mainly because no one could work with me. Actually, I like everything I do, and the physicality of working the vineyard is very important. It is something we have lost. I am a big believer in the notion of vigneron. In the industrialized world we have become very good at turning things into industrial processes. You grow grapes; I’ll learn how to make wine – we all become specialists and you lose your connection with the product.’

Tim Philips: In a good year I will get a hundred kilos from a tree, in a less good year 20 kilos, there is very little labour involved. These are all cider varieties and in the vineyard they are all eaters. In theory I should be planning it – thinking I can’t have this many oak trees. Just look no one could design this could they. If you look from above, isn’t it interesting how you’ve got this long line of trees here – and in this area here, nothing.

This was just a farmer’s field when I got it. These are perry pears. I reckon on Sauvignon Blanc skins it could be pretty interesting. I did Cider Salon last weekend in Bristol and some of the Perry I tasted inspired me.

The only thing I played God at was this: I planted gorse from the New Forest. This is a nitrogen fixer and it burns very hot so people used to use it for fuel. It’s a joyous thing, great for birds, things can live in it, it offers sanctuary from big predators and they flower all the time. Not just Springtime, they flower whenever they like. I’ll let the brambles here go for about 5 years and then I will go in and clear them, if it weren’t for the brambles everything would be grazed off by the dear. After ten years, it was 80% bramble. I think this is going to be a fantastic agricultural project.

Lisse: How did all this come about Tim? I understand you used to be an accountant – a useful skill in this game.

Tim Philips: ‘I was an accountant yes, travelling all the time, corporate – then I got posted to Italy, and lived in Rome for three years. Life changed a lot. I was working for a small company and eventually Shell bought us. I took my redundancy money and went to South Africa to study wine. I started studying wine in South Africa because I liked wine and I wanted to make it and then I realised when I was there that I really liked growing grapes. I’m never going to win a winemaker of the year competition but it is all about the vineyard. The connection with me to the land is real and it means everything to me. The sense of well-being I get doing this is epic, more and more outside the vineyard and thinking about agriculture in general.

I went to Elsenberg, with Adi Badenhorst and all that crew. I was their first and only international student. Adi recommended it: he’s a distant cousin of mine. I called him up and said, what do you reckon? He said Elsenberg was Boer-assic park, which is very Adi. I ended up at a farmer’s college: Elsenberg is there to educate farmer’s kids who have been making wine since they were five but actually they have to go and do something. I was 30 when I went.’

‘My idea was to go back to Italy and make wine there, but I went back to my folks in Lymington, and I was out on my mountain bike and there was a sign saying walled garden for sale. I thought, I’ve never really thought of growing grapes here: Hampshire is really interesting, and the New Forest is really interesting – it’s gravel, fantastic soil. But there is no slope anywhere. The owners wanted £1.2 m for this walled garden, and were insulted by my £80 000 offer but eventually after months of zero interest they accepted.

An acre of land surrounds the walled garden, rich in old cider trees, planted between 1860 and 1890 – they yield around a ton of apples a year. Four grape varieties are planted: Chardonnay, Riesling and Sauvignon Blanc. Tim has also recently planted some Pinot Noir – just 100 vines, he uses the Pinot skins for his ciders. It has taken him 12 years to finish planting.

‘I did the Plumpton sustainability course and I wouldn’t talk about grapes: I asked why aren’t you planting apples – ‘well we are doing a winemaking course’. But being more diverse is also very important. I make cider which is far more profitable than winemaking. I need my vineyard too; I need the skins to put in my ciders or they wouldn’t be the ciders that they are. If you have a bad year for grapes as I did last year, absolutely appalling, the whole idea of specialism doesn’t work so well.’

If you are idle and rich and want to invest in something but don’t want to get your hands dirty… I think that’s a shame because this is epic in terms of enjoyment. Eventually in about ten years this should be a productive orchard producing between 3 and 5 tons a year which is 2.5 to 4 thousand bottles of cider on which I make about 8.50 a bottle on of todays’ money.

This year I sold 800 bottles of cider to Les Cave de Pyrene – it was made on Pinot skins and it was very Pinot – fucked up Gamay style. I tasted it with Doug Wregg – we were tasting some wines and I told him I’d had a go at doing this cider last year because I didn’t have any grapes – and he goes, ‘Oh have you bottled it yet?’ – ‘Doug I just pressed it’ – he said, ‘It’s great why don’t you just bottle it’ – and I said ok. I bottled half of it and they bought it. By the time I did the Real Wine Fair, they’d sold it, in three and a half weeks! I had people coming in from Notting Hill wine bars asking to try it and I’m thinking – this isn’t going to go down well – Oh no no no, we’ve already got it and we love it. I even get some of those bottles back as candles – this candle maker dude does that – I mean Christ!

Cider is absolutely brilliant because it develops at a glacial pace, white wines, you want to be trying them every week to ten days to see where they’re going whereas cider – I can’t tell the difference after 4 months.

LG: Your stand at real wine was rammed wasn’t it?

TP: Yes I had people who know me tell me they came to see me but they couldn’t get near. I don’t do any marketing – people were coming to me with clean glasses – at 11am in the morning…!

LG: What’s all this growth here?

TP: I’m a big fan of hedges – I’ve got 7 different varieties – we’ve got Hawthorn, we’ve got Maple, we’ve got Guelder rose, we’ve got Blackthorn – I want a really monster hedge – all the others border other people’s land so they get trimmed back whereas this one is going to be a real monster hedge. It’s all about diversity. There are 500 daffodil bulbs.

LG: This is beautiful, this sculptural circle of cut wood and bark..

TP: Rotting wood is ideal for stag beetles – it takes a stag beetle seven years to go from a grub to a beetle – ‘you are going to be a mouth and stomach for the next 5 years’ – how did metamorphosis happen – that’s incredible – What is the main form of a butterfly? – Its only there to mate – last year I got into yew trees because I discovered two here.

LG: Aren’t Yews they the oldest living species? We have one in East Sussex that’s 4000 years old.

TP: Yew trees. The average ant lives for 4 years – the Ant Queen lives for 25 – 30 years. It amazing, if you go back 400, 000 years – there were human type people – a million years – only apes – 140 million years ago – ants and Yew trees existed and were recognisable!

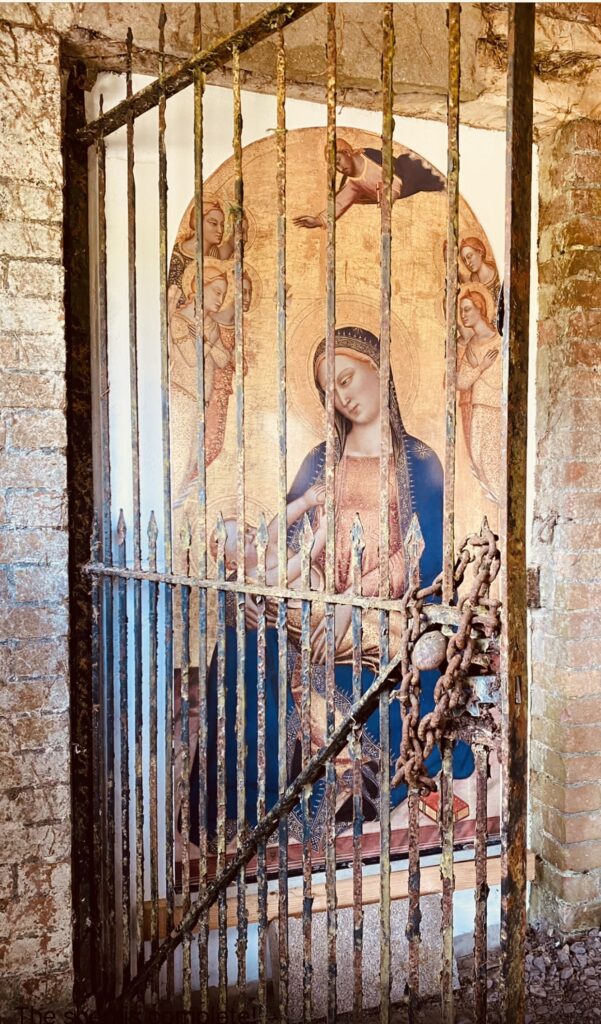

Tim Philips’ walled garden is our next stop. The garden was completely overgrown when Tim bought it, it had been locked up for years. The perfect walled garden with Edwardian glass houses built precisely aligned to the sun, avoiding shadow. There is a corner walled structure, well roofed with zinc and living grass – sturdy. Tim’s brother had just laid a beautiful stone floor when we arrived. It is here that Tim has installed his Madonna.

The garden is precisely an acre and meticulously cared for. For all Tim’s protestations he is a skilled farmer – the vines are in buoyant health, lush and green, there is a rich profusion of plant life and hens service the rows – no cock mind. Every hen is named and they allow you to hold them cooing and gently cawing with pleasure. Layla pecks happily at the grass seeds caught in my trainers. Gorgonzola is more circumspect, Tim says she’s a ‘scaredy cat’ – built on generous lines, eventually she mills around us too. Tim cleans out the hen house daily and is here every morning at 6am sharp to let them out and at dusk to put them to bed. They are carefully housed to avoid rats and foxes. Their food is cleared away for the same reason.

TP: This place wasn’t built to be nice; it was built so the people in that big house wouldn’t have to eat swedes and turnips all year like the peasants. They really understood agriculture. This wall is nigh on perfect for this latitude so that you get more afternoon sun than morning sun. You think, that was lucky but it wasn’t luck. And you get walled garden societies asking why is the glass house as close as it can be to the house? If you wait until midday on a winters day and you’ll see the nearby stable block shadow just kisses the bottom of the wall. They built it as close as they could to the house without getting excess shadow.

Tim grows Chardonnay, Pinot Noir, Riesling and Sauvignon in dense 1.5 m rows on cordons which he says love the walled garden.

TP: The only issue with the Chardonnay is that lower buds when pruned tend to be less fruitful as they get less light so I changed the wire height on these as there is no frost risk and far better air circulation. There is long grass between the rows which is a great trade off, bringing biodiversity and insects in spite of potential humidity issues. The Sauvignon is lime green and took an age to get right, it’s tricky to grow, very unruly. You can see shoots with nothing and this is not a bad year but it is screaming at me, go to cane pruning which I have started to do at a lower height. The Riesling I probably won’t go to cane as it seems to work. Fundamentally as plants these vines are really really happy.

For me it takes a long time to get to know a piece of land, it took me seven years to get to know this, I lost a whole crop to powdery mildew in 2014 because I just didn’t understand. You need to know your site. You see how dense this Sauvignon is before I thin it, the same with the Chardonnay, rampant. In stark contrast this is Riesling, you can see the tougher leaf. Chardonnay wants to get powdery mildew all the time but this is far more robust, more natural vigour control. I had thought I was wasting my time for years but it now sets a brilliant crop. For me it’s an absolutely fantastic varietal, generally goes to sparkling after 4 years on lees. In 2020 I made a still out of it. For some reason the acids dropped right off. In this country and on this site it’s a fantastic varietal.

Vineyards are hard because of the nature of the way you are growing stuff; you are excluding plants but I don’t have any mildew. Chardonnay is the trickiest in our climate. I know of a place in Umbria who have about 28 varieties and anything they want to have high acidity they cane prune and anything they are not worried about the acidity dropping they spur prune. It does occur to me, what am I losing, some fertility potentially definitely with more wood I would get a lot of less deficiencies like magnesium deficiencies because you’ve got a lot of permanent wood. Most of my wines aren’t very acid, they have a slightly limpid, not aggressive acidity. Who knows if it’s something to do with that pruning reserve?

The soils are fantastic, they are springy, no machinery, really aerated and big root systems. I still tell people in the UK, end of year one cut the vine down to the base. That’s in part because of my South African training which dictates you’ve got to get the roots down. In a dry country like that if you keep pushing – the vines go out of balance because they are so vigorous. I did it here at the end of the first year. Perversely I think I like things that take a long time, I’m just not in a rush.

Biodiversity brings me insects and helps me in ways I can’t even pretend I understand.

We taste Perfect Strangers, Tim’s cider, the label beautifully illustrated by his daughter Iris and inspired by a book by Tom Philips (no relation)

TP: Perfect Strangers 2018 Cider – A mix of eaters and cooking apples from just behind the walled garden. Midway on pressure, 15 grams of tirage, I don’t want Champagne pressure. It can be still, white, red and fizzy…impossible to call, it all gets called the same thing.

Jamie Goode: What I like about this, the VA is really under control but its got that really nice spicy bite, the acid line is really nice.

TP: So for me Jamie, that’s picking the apples off the trees. If you pick off the ground like most cider people do I think you are limited in what you can do. Your VA has started, you’ve got light bruising and they’ve gone three- or four-days bare minimum, so your VA is going to be .7 .8 before you’ve even started so you can’t be thinking about 4 years on lees can you.

JG: I think that’s the key to really nice cider. I’m not a massive cider taster and expert but I don’t like it when the volatile acidity is too high.

TP: I’m immediately put off and it can be very interesting in every other way. It’s a lot easier to make an alcoholic drink of 12-13 % alcohol than it is at 7%. You get flavour and interest with alcohol, it’s very hard to make an interesting beer at 2%. You can serve this as an aperitif without people getting blotto. This is just over 7% and its had no skins, it had the tail end of a still cider which had Shiraz in it. So its probably about 1-2% made up of the Shiraz lees at the bottom. It’s essentially red wine lees. Without it its very neutral and quite boring. Some say it’s nice but I don’t like nice, it’s not a great attribute. We sell this for about fifteen quid.

If you find a good producer all of their wines should be good. But you should always be able to get something for fifteen quid and this sits in the bubbly category.

We taste a work in progress, 100% Chardonnay from a solera bottled in 2014. Nearly 8 years on lees, Jamie describes it as mealy and dense.

LG: Are you from farming stock Tim?

TP: My mum and Dad were musicians who met at the D’Oyly Carte, an opera company that performed Gilbert and Sullivan. A flautist and bassoon player. They were quite progressive and when they got married my Dad said two travelling musicians will never last so you keep going, it’s much easier for a man to find a job. He went to work in Southampton Docks when the shipping companies still cellared wine. He worked in the warehouses cataloguing wine, got interested, bought the World Atlas of Wine and started buying anything that had a label on it as it came through at cost. So I’ve got 1942 DRC La Tache and others, he then started a cash and carry, then he ended up becoming a wine merchant. We blind tasted a lot together. At that time wine was a closed class shop.

Later he became a vicar, not sure he ever really believed in God, he was more Buddhist than anything else. He would let the homeless people sleep in the church but only when he could because a lot of parishioners didn’t like it.

LG: This is a lifestyle choice as well as a means to make money for you isn’t it Tim? It reminds me of the people with allotments next to my house, its magical what they can produce out of a tiny shard of earth.

TP: When you get connected to ground its intensely powerful. You become very rooted as an individual. If we as families had just an acre each just think what we could do with it. Just look at the yields per acre of allotments, it blows commercial farming out of the water. Industrial framing is complete horseshit. But the secret is to stay small.

I can sell two thousand bottles of wine in an open day, that’s 15 grand in a day. Bottom line I am making 20 something out of this which isn’t enough to keep my family in the lifestyle to which they have become accustomed but I do about 25 days a year of finance work and that pays the bills. School prepares you for a standard drone life but there are ways around that system. I wouldn’t even think of doing these things, like building my own house if I didn’t know people who could help me.

THE WINES

Riesling is an interesting choice, because very few have tried this in the UK. The vines now seem to be in a really good place, with decent fruit set and canopies that are balanced and hardly need topping, unlike the vigorous Chardonnay and Sauvignon.

‘I planted Riesling because I wanted to make a still Riesling, because I think it’s amazing. If you’d spoken to me more than 8 months ago I’d tell you you haven’t got a chance in hell of ripening Riesling. It was always as tart as heck. From 2010-2012 I put it in the Chardonnay and hoped that no one would notice. Then in 2013 I had a bit more and made Riesling on its own, and after four years on lees it was insane. I have to love what I do: there’s precious little money in this. I have to love what I make.’

Production is 2500 bottles, sold direct. Tim calls his business plan ‘peasant economics’: his costs are very low. There’s £40 of petrol a year for the backpack sprayer and then 6 posts a year at £4-9 each.

Perfect Strangers Cider 2020

8.1% alcohol. This is made with dessert and cooking apples from 106 year old trees next to the vineyard but outside the walls. Some of the trees have three different varieties on them! It spends three months on Riesling skins, and then it’s later infused with wild hops from near the winery. ‘Without the skins it’s really boring,’ says Tim. Vinous, complex and layered with some appley notes but also nicely complex fruity notes, with some bite on the finish. 9/10

Perfect Strangers Cider 2018

7% alcohol. This has some colour from using the lees from the tail end of a batch of cider that had some Shiraz in it: the lees have coloured it up. He had no skins available. It’s a pink/orange colour and is lively and bright with good acidity and some appley notes. There’s a spicy bite to the acid that’s really nice. 9/10

Charlie Herring Promised Land Riesling 2017 England

Traditional method sparkling. This spent three years on the lees, with 2 g/l residual sugar. Very lively and fizzy. Limey with nice citrus drive. So pure, citrussy and precise with lovely purity to the fruit. 91/100

Charlie Herring Promised Land Riesling 2020 England

This is the first still wine he’s made from Riesling, and it’s spectacular. Lime, spice and mineral on the nose. Grainy on the palate with some white pepper and mineral. So focused with ripe fruit and some lime. Has a salty element to it. Crystalline. 92/100

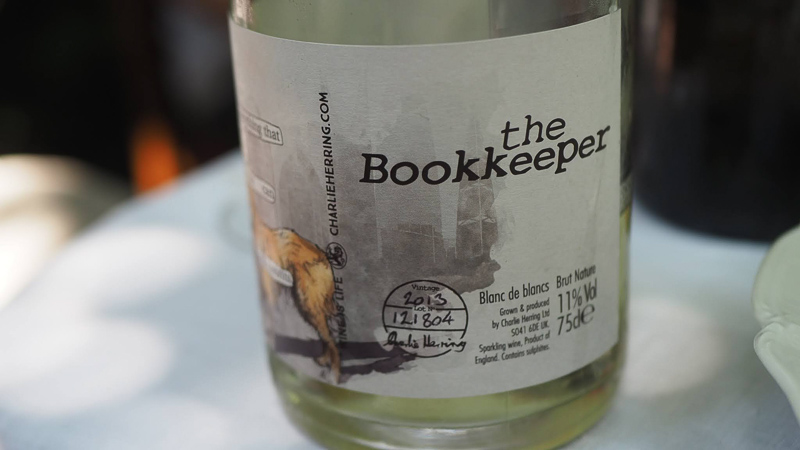

Charlie Herring The Bookkeeper Chardonnay Blanc de Blancs 2013 England

Disgorged December 2018 with 4 g/l dosage. Very fine and spicy with citrus, peach and a touch of spice. Mineral but also has ripeness and a touch of honey. Lovely volume here with good precision. Tapered and finely spiced. 93/100

Charlie Herring A Fermament Sauvignon Blanc 2018 England

Lovely textured, balanced wine that’s really expressive with some elderflower, and supple pear and apple fruit. Lovely balance here with a nice stony edge. 94/100