Exploring smell and the art of the perfumer, with Dr Melanie McBride

As a wine person, I’m deeply interested in smell. It’s a sense that lies at the heart of gastronomy, and that includes wine. Remember: a lot of what we think of as ‘taste’ is formed by a combination of senses, with smell chief among them.

Over the last few years I’ve been thinking a lot about the perception of wine, and the nature of this experience. I even wrote a book on it. But I’m still learning, and with this in mind on a recent trip to Canada I stopped by the Metropolitan University to meet with Dr Melanie McBride who is a researcher in the Responsive Ecologies laboratory (RE/Lab). Melanie has done a lot of work on smell, and I quoted some of her ideas in I Taste Red. A particular emphasis of hers is smell in the real world, based on actually smelling things, developing a knowledge of the materials, and not just relying on book knowledge. I spent a few hours listening to her, getting practical in smelling things, and then working on blending smells using skills learned in the real-world experience of smell.

‘With smell, people fall into two categories,’ says Melanie. ‘There are people interested in smell as a looking glass, as a reflection of themselves. This is the main thing: people come and tell what they know about the smells. Far fewer people want to engage with the material, and smell the material.’

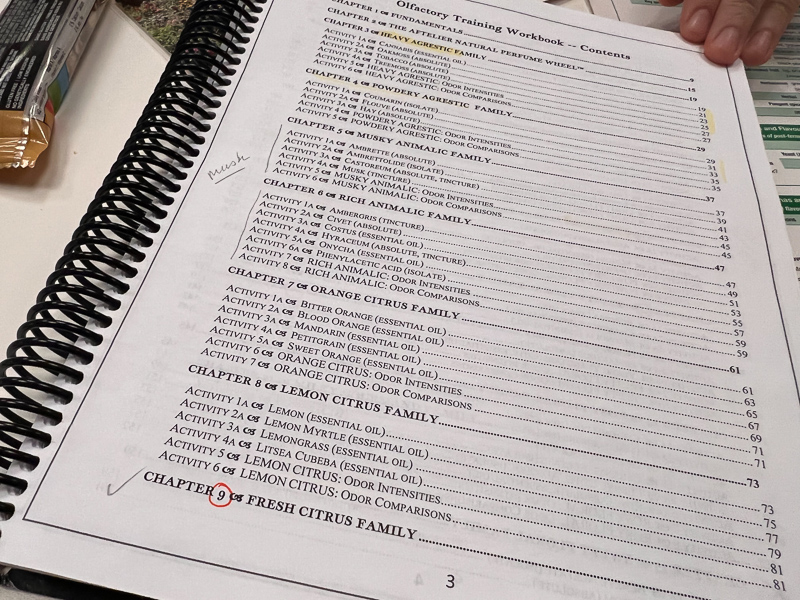

She is a big fan of perfumer Mandy Aftel, whose teaching is very much focused on the actual materials, rather than theory. ‘She adores the materials,’ says Melanie. ‘You have to listen to what the source is telling you. But students memorize the stuff in the book, and their knowledge gets in the way.’

Melanie cites the work of psychologist James J. Gibson, who said that perception is not a mental process, but rather a reciprocal process that requires a contribution from the environment. In order to perceive we need a range of affordances: we need physical proximity to the source, air, light and other affordances, all of which contribute to the possibility of perceiving. Perception is a bottom-up process, beginning with the source. With wine, a lot of people first establish typicity and then from this try to work out what is in the wine, rather than dwelling in the wine, and focusing on what is actually there when we sniff and taste.

In her laboratory, Melanie has established an apothecary of smell objects. She divides this up into three areas. There’s the chemistry side, then two sections of history side, which is divided into ancient and modern. We spent some time smelling and discussing.

We began with a famous smell object: ambergris. This is made by whales, and is found not farmed. It begins as a waxy substance from the whale’s head that helps with echo location. This then forms a protective layer around the hard beaks of squid the whale has eaten, as a way of making them less sharp. This congealed material passes through the whale and then floats on the ocean, where it cures in salt water. Over time it develops a lighter colour on the outside, and develops the sorts of aromas that make it so highly valued. It then has to roll up on a beach and get discovered! Melanie’s example has been tinctured, which means it is put in a medium of perfumer’s alcohol. It smells quite wonderful: deep and bassy, with lots of nuances.

She explains that there are a lot of things in perfume aroma that need to be on the body for them to be smelled properly. ‘Like wine, you have to drink it,’ says Melanie. A component like ambergris ‘dances with the other ingredients’ once it is in the perfume.

The next thing we looked at is onchya, also known as devil’s fingernails. This is the operculum of a mollusc, and it smells of shells with a smoky note. It’s a spicy, dark, musky smell.

Then, choya nakh, which is made from a distillation of dry roasted sea shells, and has a wonderful smoky note. It’s quite remarkable.

Then rock rose, which despite the name is not at all floral. It makes cistus (from the flower, it smells green and fruity) and labdanum (which is smoky and resiny).

White musk is interesting. This comes from plants, and the one I’m smelling is Ambrett (olide) from hibiscus flowers. It’s sweet and delicately musky.

Costus root is another powerful aroma. Animal, stinky, leathery, wet dog, greasy hair. But it also has ionones, as it is a root (orris root has ionones that make it smell of violet).

Hyracium is a non-violent musk. It is made from a rock on which stone hyrax have been urinating for thousands of years, and the rock is harvested with all these layers of urine. It is leathery with barnyard notes and has a spiciness to it: warm and inviting.

Some smell sources are quite unusual, such as Castor canaidensis: these are beaver scent glands, and they were once part of Chanel No 5. Lots of spicy bretty characters here.

Civet. This comes from the anal gland (most, alas, is not ethically harvested), which is used to make civet paste. This is cured and it becomes more floral, with indole.

Melanie says that learning to smell the components is like learning to play the guitar. Practice is needed. And repetition.

Oud is made from agar wood, and is an expensive base note.

We then looked at a perfume made by Mandy Aftel for Leonard Cohen, titled ancient resins.

‘I’m interested in learning, and how people learn,’ says Melanie. ‘If you want to understand aromas there are many ways of doing this, but many aren’t real practices.’

We then looked at some related aromas that people commonly get mixed up. Violet leaf, which is green and floral (not beta ionone); Beta ionone which is violet flower, and the green side of violet; and Alpha ionone which is the candied floral side.

How do perfumers learn? With Mandy Aftel, they work on categories which are done as a cluster. ‘You practice with clusters of similar things,’ says Melanie. ‘For example, three clusters of citrus.’ Getting to know your material is key. ‘There are certain things you are looking for in assessing a perfume: it is not just how it smells, but how it evolves,’ says Melanie. ‘It is like a piece of music. Each part is cool, but they are different, and you need the whole thing, so you need to track how it evolves.’

A perfume can be broken down into its individual materials by a skilled perfumer, and then even a molecule can be broken down into facets.

For example, you can run orange blossom across a GC (gas chromatograph) and then see the peaks, and from these choose an orange blossom scent with lots of indole. And each type of lavender essence is like a wine: they are all different. She has tried lots of different examples of linden, and they are different. But synthetic linden is just one molecule: farnesyl.

We looked at some more sources. Mimosa is very pretty: white flower smell. Acacia smells like methyl anthranilate, which is the smell of labrusca grapes, and is also found in mandarin orange.

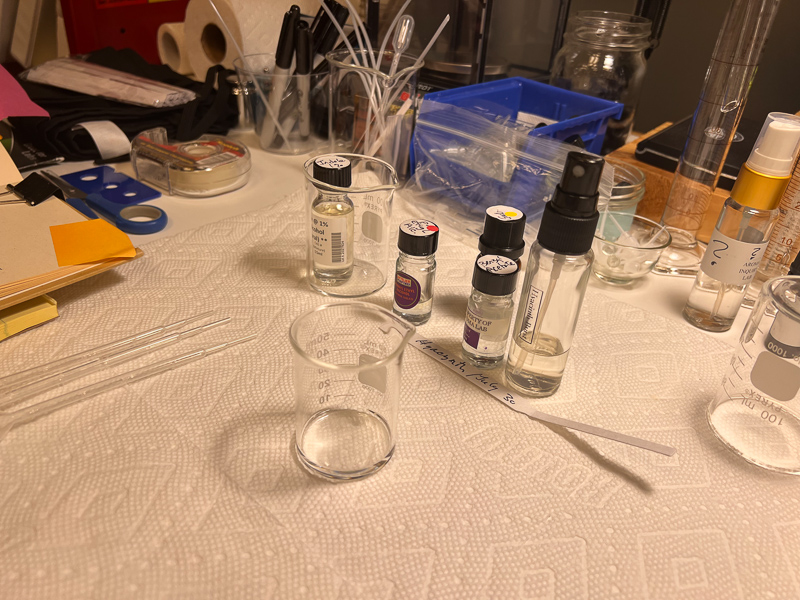

Then it was time to think about creating perfume, using drops of natural essences. We focused on rose.

Rose oxide has a green stemmy character and is spicy, and this is not needed in rose. Actually, it turns out that phenylethylalcohol is the rose note, found in lychee and rose petal. But the wine world seems to think that rose oxide is the significant chemical in the aroma of Gewurztraminer, which is a mistake that perpetuates because people don’t bother smelling the source molecules.

To make a rose perfume we used the following:

- Phenylethylalcohol

- Citronellol

- Geraniol

- Damascenone

- Some rose absolute

- Nerol

The budget was set at 20 drops altogether, and we spent some time varying the proportions until we got something convincing and really nice.

Playing with the different combinations helps you understand the materials. And Melanie says that with knowledge of materials, you can certainly discern more than four molecules in a mix. She emphasizes that choices in blending should be deliberate, and you should be able to explain why you made them.

But there are problems in the world of smell and perfume. Too many people are relying on book knowledge, rather than actually smelling things. ‘I’m not against books,’ says Melanie. ‘I’m against this mind-over-matter logocentric deference that refuses to engage. People are afraid of engaging the world.’

‘Without literacies it’s whatever I decide it is, but if you have literacy, anything can’t be anything.’

The implications of all these ideas for wine? I think we should be training our sense of smell by putting in time smelling source materials. Look at the descriptors used in wine education, or by writers trying to describe wines. Shouldn’t we be spending time smelling these? How true are the various wine kits that offer a sort of training in wine-related aromas? In many cases, real world aromas are hard to mimic with synthetic chemicals in simple blends. We run the danger of developing a somewhat imaginary lexicon if we don’t spend time working on smell.