Exploring Blaufränkisch at the Blue Frank Think Tank (1) the presentations

Sevnica, Slovenia was the setting for this conference on Blaufrankisch, an interesting grape variety that looks to have a promising future. It’s known by many names, including Modra Frankinja in Slovenia, Lemberger in Germany and Kekfrankos in Hungary. [For the tasting of Blaufrankisch that accompanied this seminar, see this link.]

‘This is a great grape variety that can do marvellous things,’ says Robert Gorjak, a winewriter who lives in Ljubljana, Slovenia, who was moderating this conference. He added, ‘times are good for Blaufrankisch because people are searching for new things. They are searching for grape varieties that have vibrancy.’

Ozbej Peterle, from the University of Ljubljana, talked of the new beginning for Modra Frankinja. It’s 4% of Slovenia’s plantings, concentrating in the east. The average size plot in Slovenia is 0.5 hectares, split among 30 000 growers, and although 27 000 of these make wine, only 2300 bottle it. Posavje is the most important region for Modra Frankinja. There are 18 400 ha altogether in Europe: Hungary is the biggest with 8000 ha, Austria has 3200 ha, Germany has 1900 ha and Slovenia has 632 ha (2020 figures). Outside Europe, it’s also in Australia and USA among others.

The new beginning? ‘This is a grape variety with potential for making high quality wine,’ says Peterle. ‘Each bottle has a story to tell: it expresses the terroir. It’s versatile in that it can make red, sparkling and rosé. It’s regional and not so international, so it has a point of difference. And quality of the wines is on the up.’

Room for improvement? ‘Clone selection, and also matching it better to vineyard plots. Viticulture can be improved. Too many people don’t get it right in the cellar. The search for style is also underway.’

David Schildknecht followed up with a detailed talk on the stylistic evolution of an enigma. He took us through the historical references, which he described as very muddled. ‘The history is very hard to pull out.’ An imperial wine exposition in 1862 is thought to be the first explicit reference to the variety. It says it is known as Lemberger in Germany and is frequently confused with red Burgundy. ‘It is obvious that this isn’t a grape variety that suddenly appeared out of nowhere,’ says David.

He adds that the 1862 reference is midleading. ‘The 1862 reference always gets cited but no one ever reads the entire reference.’ Schildknecht adds that the author mentioned Schwartzriesling in 1835 where it emerged in Thermenregion as a blending grape to add something to Pinot Noir. Later commentators referred to the two Burgundies.

The earliest references are from the end of 18th century under the name red Burgundy in Horitzon. ‘This could be the origination,’ he says. References to planting Lemberger in Wuttenberg begin in the 2nd 3rd decade of 19th century. Two lists from the 1820s have Lemberger wines on them.

But Lemberger is only recently famous in Germany. He points out that up until the end of the 1980s the acreage in Germany was less than that in Slovenia today. It only emerged as a solo grape variety in the 1990s.

Schildnecht says that it’s difficult to get eyewitness accounts of what Blaufrankisch tasted like in Burgenland in the 1960s and 70s, but the acidity suddenly emerged as a potentially positive factor when Austria was trying to revive their viticulture. German tourists wanted fresh, bright high acid whites, and lively reds. ‘There was a tendency to superficiality in Bluafrankisch. The turnaround was Triebaumer, he made a wine in 1986 that got placed in a prominent blind tasting and it blew everyone away.’

‘It takes a few years, then the seminal year is 1992 – some of his colleagues got serious about Blaufranckish.’ The likes of Feiler Artinger and Nittnaus started making interesting wines. ‘The start was slow. Things were very tentative.’

‘After this early flourishing in the 1990s, Austria got increasingly serious about their red wines. Red wine got pulled along by some of the famous whites.’

But the Austrians lost their way a bit. ‘The grape is high acid what can we do to compensate? Pick later. The wine is modest in tannin, but wood has lots of tannin, so put it in barrique. The wines taste sweet and sour so sweeten more with oak.’

‘A strong trend developed for making BF that could stand international comparison, and as a result was less distinctively Blaufrankisch.

In the late 1990s Schildknecht began tasting a lot in Burgenland. ‘I found this old atlas with pictures of old clusters from 1877 they were small clusters with thicker skins and you could see right away that this was a different animal. Clonal selection began moving away from the large bunches with thin skins.’

‘Uwe Schiefer and others then began getting serious about Blaufrankisch, using open top fermentation, some whole clusters, different sort of barrel regimens. Then Moric in 2001 started taking lessons from the Rhône and Burgundy. At that point we begin to see a tendency to less extraction and less oak, and embracing the positive aspects of high acidity in the grape.’

‘There are more and more people working with this grape who are interested in old vine genetics capturing this with selection massale. There is greater sensitivity to extraction, whole cluster and shorter vatting, and a move to larger barrels, and extending elevage. None of these are trends that are peculiar to Blaufrankisch.

‘What we see now is a tremendous stylistic diversity. There is no longer the sense that there has to be a notion of where we are headed. What should be the style? Is there a court of stylistic judgement? Now we have passed a point where this will never be an issue. People will find their way.’

A change of pace. Dorli Muhr was the next speaker, and she talked about how Blaufrankisch became became the love of her life. She was born in Carnuntum and had very little appreciation for the wines of her region. She fell in love with wine during a bicycle tour in France. It had an intellectual appeal: how can you taste where a wine comes from? She started translating books such as those of Peynaud. She founded a PR agency called Wine & Partners. But more and more she wanted to make her own wine. She thought it would have to be France or Italy, because she thought great wine could only come from there. She bought a property in Tuscany in the late 1990s with a view to planting. She went home and did some calculations and realised it would never make a profit.

She moved to Portugal and to the Douro – a short but important element in her life (Dorli married Dirk Niepoort, although the marriage was not a long one). She learned there is nothing better than old vines, and there is nothing more attractive in wine than freshness. In the Douro, the real skill is to get freshness, not maturity. Dorli realised her Tuscan adventure was over. So where could she make wine with old vineyards, where she could get freshness? She went back to the place she was born.

The Spitzerberg is the eastern-most hill in Austria. So with Dirk she started to make wine there in 2002 and it was terrible. She rented an vineyard with 1965 plantings of Blaufrankisch, and in 2003 they did the right things. They weren’t sure Blaufrankisch was the best variety, so the planted Merlot, Cabernet Franc, Syrah and Malbec to see what happens. Carnuntum has quite hot summers and cold winters, and from mid-September there are cold nights. The rainfall is low – 280-400 mm a year, usually middle of May to beginning of July. The Huglin index is 2000 and getting higher. Perfect for Cabernet and Syrah

The plantings they did were quite correct, and they’ve seen great results with Syrah

But with all these nice results, Blaufrankisch always gave the best results: it reflects place much better.

Carnuntum has Sandy limestone soils, and the old flow of the Danube brought gravel which is found on the lower parts. Also, old lakes left sedimentary soils. There are 900 hectares of vines but different soil types. 55% of grapes grown here are red, 45% white. Zweigelt is the main red, with Blaufrankisch 11% of plantings.

Dorli created a group of producers, and did blind benchmarking, getting everyone to share their details. She invited famous Blaufrankisch producers to come and taste and discuss

What is the niche for Spitzerberg?

They looked at different winemaking approaches, destemming and foot treading. ‘We discovered that BF expresses itself the best the less we interfere. It doesn’t like to be forced into a direction. It is a free spirit.’ Spitzerberg has 90 hectares of vines and she works on 12 ha, with 11 ha of Blaufrankisch. Then she regrouped the wines by the sub-vineyards of the Spitzerberg and it wan eye opener. No one had thought about this before. These lieu dits were very different. Since then, she fought to get wines labelled by according to their Spitzerbeg lieu dits.

Mike Beneduce was the next speaker, representing the USA. He’s based in New Jersey, where his farm is called Beneduce Vineyards. In the USA, Oregon and Washington State had some of the earliest plantings of Blaufrankisch, but some of these are being ripped out. The problem is economics even though many of the growers love the grape.

The East Coast historically limited winery licences by population. One licence for wineries per million people. Since this finished there has been an expansion of wineries. New Jersey has 30 ha of Blaufrankisch, and it is made by 25% of producers, and it is trending up. In the Finger Lakes it is known as Lemberger and occupies 30 hectares, trending up, but grown by fewer than 10% of producers. Washington State has 20 hectares, it is grown by fewer than 2% of producers, down from 100 hectares. There are minor but expanding plantings in a number of states.

Beneduce was an old dairy farm. His parents bought the farm, and with their Italian heritage there’s a winemaking culture. Mike studied at Cornell, and planted the vineyard while still studying. He has 10 hectares of vines, growing a hectare a year, with a potential 20 hectares, 200 m elevation and 10% slopes. Double guyot training. GDDs 1800, with winter minumums of -15 C, which is quite cold but plenty of viniferas can survive this. Blaufrankisch has good cold tolerance. 1000 mm rain a year. He also grows Riesling, Gewurztraminer and Pinot Noir.

Why Blaufrankisch? The USA has no indigenous vinifera varieties to farm. Mike decided to pick a grape that would be well adapted to the environment and grow well. It is the earliest budding, latest ripening variety they grow, so frost can be an issue. Downy mildew is a big challenge because of the humidity. The fruit is resistant to botrytis because of the bunch architecture. ‘It’s bullet proof,’ he says, which is useful, because this is the main challenge in the region. It has upright growth and large leaves. Makes it easy to work in the vineyard.

It’s a potential key variety for New Jersey to build the regional brand around. The Pinot Noir of the east is how it’s described. It has a wide range of wine styles. ‘We’ve only been growing it for 12 years so we are exploring styles that are suited to young vines,’ says Mike. The wines have labels based on Italian hand gestures. There’s a PetNat rosé, which retails at $40. It’s good for cashflow. Then there’s a dry rosé, with bright acidity and pale in colour. The still red Blaufrankisch is harvested in late October, and it’s aged 18 months in barrel and then large cask.

‘It is completely different every year we grow it,’ says Mike. ‘It really changes with the climate. We have different weather from year to year. In cooler years, we get more black pepper, smoke, gunflint and tart red and blue fruits. In a warm year there are warmer spices, with cured meat aromas and blackberry, mulberry and plum.’

There’s a bit of name confusion: everyone uses their own name. These regional names can be confusing. ‘We’ll have no New Jersey Lemberger in our state!’ he says. ‘If we are going to be marketing this, we need to choose the same name.’

They sell 100% of their wine from the farm so they have a unique opportunity to educate the consumer. ‘Fear not the Umlaut!’ is the winery slogan.

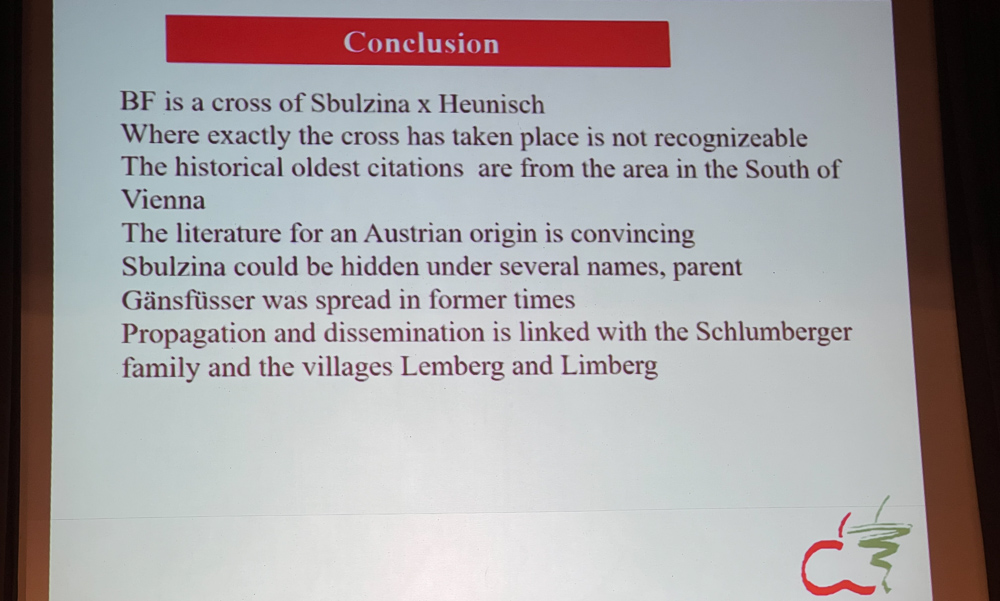

Ferdinand Regner was the next speaker. He’s a scientist who has looked at ampelography and the origin of grape varieties. ‘The number of synonyms for BF was already a problem in the 19th century and so the name Blaufrankisch was decided on at the second ampelography conference in 1873,’ he says. ‘How do you find the origin? History and genetic analysis are two routes. There are uncertainties in the histories because you can’t be sure they are talking about the same variety. As for genetic analysis – sometimes alleles differ from those of the parents, not often but sometimes.’

They began using SSR markers. With 6 they could identify varieties, but they added 3 more to get to 9. But to trace the heritage properly you need 40 markers. They identified Heunisch as one one parent (this is also known as Gouais Blanc), but they couldn’t find the second among well known varieties. Then in Italy a rare variety that’s late ripening in Friuli was found: Sbulzina. This was later found later in a German collection where it was called Blaue Zimmettraube. Two years ago Vranek was found to be the true Blaue Zimmettraube, and Sbulzina isn’t the same variety.

So Blaufrankisch is a cross between Heunisch and Sbluzina.

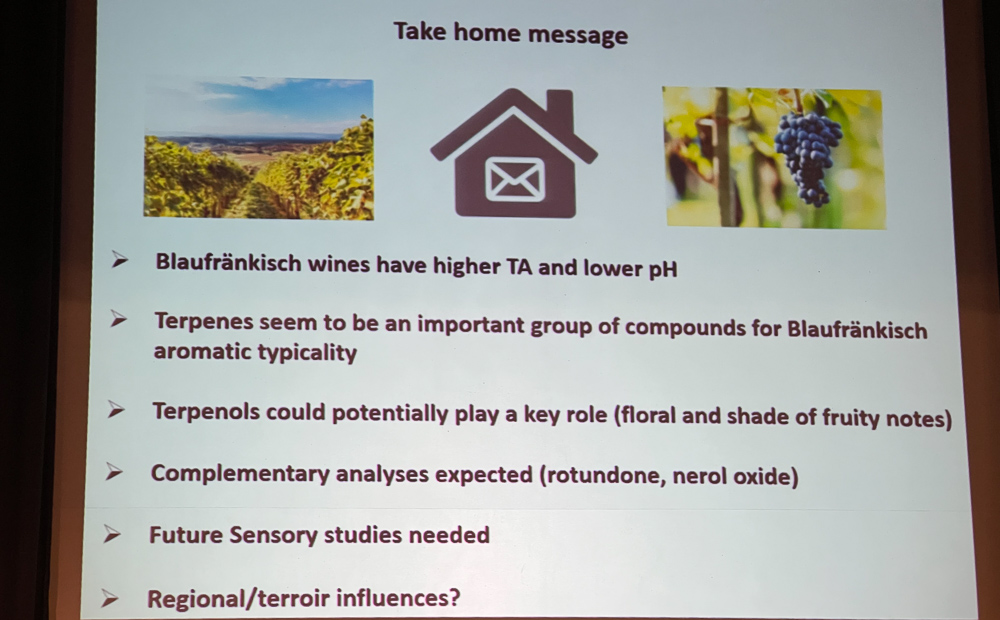

The next speaker was scientist Guillaume Antalick, who has looked at the chemical calculation of Blaufrankisch wine typicality. In terms of flavour, it’s a variety known for freshness and acidity, red fruit, tart fruit. ‘It was difficult for me to find any mentions of Blaufrankisch in international journals,’ says Guillaume. ‘As an expert in wine aromas I couldn’t find much.’ So he decided to start to work on it. He selected 40 examples of Blaufrankisch, 18 of Pinot Noir, 18 Bordeaux blends. This project was a collaboration between the universities of Bordeaux and Nova Gorizca (Slovenia).

Guillaume targeted pH, TA, astilbin isomers (markers of sweetness, recently identified by Alex Marchal). And for aromatics: esters, C6 alcohols, terpenes and norisoprenoids.

Astilbin isomers are natural sweeteners, and Pinot Noir has lots but not Bordeaux varieties and Blaufrankisch. ‘It’s not easy to work with wine tastes,’ says Guillaume, ‘so it’s hard to know where the sweetness from Blaufrankisch comes from.’

What about wine aroma? There are different categories. There are primary aromas that come from the graoes. These are at different levels – some are present in the free form such as pyrazine. Pepperiness in Syrah and Blaufrankisch come from rotundone (which is now being analysed). And then there are aromas released by yeast – grape composition affects this a lot. Then aromas that are synthesized by the yeast, and finally tertiary aromas from ageing.

Esters – made by yeasts but grape composition affects their production. The esters are actually pretty stable after fermentation, and it’s other things that affect fruity aromas going further down the road. Guillaume found some differences, but not too many.

C13-norisoprenoids, come from the grape as precursors, and fermentation reveals them. These include beta-damascenone and beta-ionone, both important in wine aroma. Blaufrankisch has higher TDN, and much higher vitisin, but they are lower than sensory thresholds. This doesn’t mean they won’t contribute in some way to global aroma, though.

Terpenes and terpenoids are a very important group for plant and wine aroma. At lower levels they can be important in red wine with synergistic effects, giving floral notes in addition to red fruit characters. Blaufrankish has higher levels of these terpenes, so what is their sensory impact?

Rose oxide has a distinctive aroma, and Blaufrankisch has more of this than the Bordeaux varieties, at the same level as Pinot. There’s another compound that’s quite newly discovered in wine called nerol oxide, and there are much higher levels in Blaufrankish then the other varieties – 10 times higher – what is the impact of this in wine? It’s quite new. It is still difficult to get the standard to do the experiments.

Finally, there are monoterpenoids, which are much higher in Blaufrankisch. The sensory impact might be with floral notes from synergy with other aromas.