Bringing up a wine: the art of élevage in winemaking

Wine is a product of fermentation. Yeasts eat the sugar in the grapes and from this produce alcohol. They also produce a range of other flavour compounds, either from scratch, or from flavour precursors present in the grapes. Add into the mix the various compounds in the skins, pulp and seeds that might also find their way into the final wine, and then any contributions from bacteria (wanted or unwanted), and we have wine. But at the end of fermentation, wine isn’t ready to drink. It needs time: it needs to be raised from this primary youthful state into something that’s at the right point in its life for consumption or bottling. It’s this raising or bringing up a wine that is described so beautifully by the French term of élevage. The mastery of élevage is one of the great skills of winemaking.

There are a number of vessels or containers used to bring up wine, and each have their benefits. Think of them like the various pots and pans in a kitchen, where a chef will use different ones for different roles. Two of these achieved a primary role in cellars worldwide, but over the last few years things have been changing, and as well as return to the past, there are new tools of élevage that have been widely used. Here, I’ll try to sum them up, and explain their advantages and disadvantages.

Stainless steel

Stainless steel tanks are probably the dominant means of raising a wine, and most wineries will have quite a few of them. They vary in shape and size, but are mostly tall cylinders in order to maximise space. The typical volume will be perhaps 5000 litres, but can be smaller, or much larger (50 000 litre tanks are common in big wineries). The advantage of stainless steel is that it is inert (it won’t react with the wine or transmit flavour to it), it doesn’t allow any oxygen in, and it’s relatively cheap. Some tanks have two layers of steel, with a small gap between them in order to allow for circulating liquid that’s hot or cold, in order to regulate the temperature in the tank (especially if it is also used for fermentation or cold stabilization before bottling). The disadvantage of stainless steel is that it conducts heat very well so temperature during fermentation can vary, and yeasts don’t like this, and also that because it doesn’t allow any oxygen in the wine can sometimes develop problems with volatile sulfur compounds, and may not develop in favourable ways (for some wines, a tiny bit of oxygen can be helpful, especially red wines). Some tanks have a fixed capacity, but others are know as variable capacity (VC tanks). Here the lid can move up and down so it is on top of the wine, preventing a headspace with any air in it. The seal is made by a pneumatic plastic tube a bit like a thin bicycle tyre that runs around the rim, and which is pumped up and kept inflated. These need to be checked regularly because if they deflate, air can get in, which is a bad thing.

Tanks can also be made of fibreglass (these are common in smaller wineries in France, I’ve found) which is a bit cheaper than steel. And I’ve seen Russian wineries with cast iron tanks, which have to be lined with epoxy. These are problematic: if wine gets into contact with iron, it is likely to oxidise quickly.

Wood

Oak barrels are a very common way of bringing wines up, and in particular small oak barrels of around 225 litres are very popular. They are made of thin planks called staves, typically around 25 mm thick, which are seasoned (left outside for two or three years, or seasoned indoors using a special protocol) and then assembled, with a source of heat such as a small fire or steam to allow these staves to be bent into shape. The barrel is assembled using metal hoops called staves, and end pieces are put in place, with a small hole called a bung along one side to allow wine in and out. Barrels do two things: they allow a very limited amount of oxygen to enter, which can be beneficial in bringing up the wine, and they also contribute a bit of flavour, especially when they are new. How much flavour they contribute depends on the age of the barrel, the way the staves were heated to bend them, and the sort of oak used to make them. Oak contributes flavours of vanilla (from oak lactones), spice and even some toast and smoke, as well as some structure (tannins). New oak gives more flavour than old, and American oak gives more of the vanilla flavour than French oak. Some barrels are made from Eastern European oak, which tends to give a more savoury, spicy flavour to the wine.

Of late, there’s been a bit of a back to the future movement in wine. Before stainless steel was common in wineries, they would often use very large barrels of thousands of litres to age wine, and as these barrels were large (low surface area to volume ratio) and old they contributed little flavour, but they did allow a bit of oxygen transmission. Known variously as botti, foudres or fuders these large barrels are now back in fashion, even in wineries that previously had got rid of all their large old oak in favour of small barrels. And sometimes winemakers are favouring barrels of 500 or 600 litres instead of the 225/228 litre barrels for similar reasons: there’s less oak impact and a slightly slower development.

In addition to oak, other woods are sometimes used. Chestnut barrels are being used in Spain and Portugal: typically 1200 litres in size these were traditionally made by steaming the staves rather than heating by flame, and this makes the barrels more neutral than oak. They are also a bit cheaper and the wine develops a bit faster. Acacia is sometimes used for the intriguing spicy flavours it contributes. And cherry wood makes the odd appearance in Italy, but the wine develops quite fast in this.

Concrete

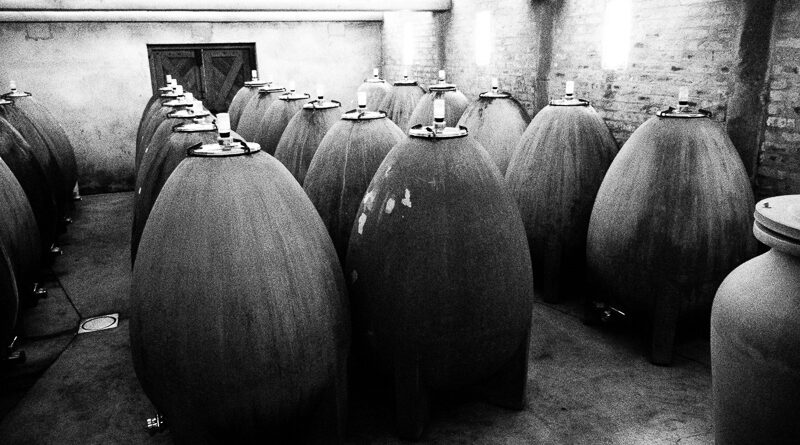

Many old wineries had a lot of large concrete tanks in them, but these were commonly replaced by stainless steel when wineries were refurbished. But there’s something good about concrete that winemakers are now beginning to appreciate. First, it has thermal inertia which means that unlike stainless steel, it can buffer temperature changes. Second, it allows a bit of oxygen transmission, unless it is lined by epoxy resin. Then there is the emergence of the concrete egg or tulip. Egg shaped concrete vessels were introduced by French company Nomblot and are now being made also by other manufacturers. They are popular for fermentation because of their shape: apparently the yeast lees stay in suspension much longer, which can be a good thing. Most are unlined, and before use their insides are painted with tartaric acid solution. They alter the texture of the wine, and give different results to stainless steel and oak barrels. Tulips are taller tanks, and the most popular manufacturer of these is Italian company Nico Velo. They are often used for fermentation, and sometimes also ageing of the wine. Cuboidal concrete tanks are also becoming a popular feature in wineries.

Clay/terracotta

Another back to the future move in wineries is the increasing use of clay vessels. In Georgia these are known as qvevri and are sunk into the ground: a winery with lots of these is called a marani. This is an 8000 year old tradition, and typically both red and white wines are made in these qvevri by putting grape bunches in, and then just sealing them and leaving them, for perhaps six or seven months. After fermentation the skins, seeds and stems fall to the bottom and the wine becomes clear. Good examples are spectacular, and this is still a very common way of making wine in Georgia. Sometimes grapes are destemmed first; sometimes the mass of skins and seeds are removed after an couple of months and the wine is returned to the qvevri once it has been cleaned, and sometimes a mix of techniques are employed. These large vessels are still being made in Georgia, and there is international demand for them. They range in size, with the largest being around 2000 litres.

Outside of Georgia, the Alentejo has a culture of making wines in talha, which are large clay amphorae that are kept above ground. The grapes, red or white, go in during harvest, typically in September, and stay there until the talha is tapped, which is from St Martin’s day, 11th November. Often the wine would be drunk straight from the Talha, but now there’s increasing interest in this old way of making wine and there are at least 30 wineries who bottle these wines, with the number growing rapidly. No one is making these large talha anymore so the old ones are prized. Many are lined with a combination of beeswax, resin and olive oil called pez, but some are unlined. They range in size from around 600 litres to 1350 litres, with most in the range of 800-1200 litres.

In Spain, the clay vessels used in winemaking are called tinajas. They are becoming more popular and are still being made there. It Italy, amphorae for winemaking are also on the rise and are the most commonly encountered manufacturer is Arte Nova. In South Africa a local potter called Yogi de Beer is making a range of clay vessels for wine. And in Oregon, ceramics teacher Andrew Beckham is making and selling a range of terracotta vessels under the brand Novum.

There is a lot of interest in wines being made in clay. The key factors include the size of the vessel, the firing temperature (the higher it is the less oxygen transmission; clay does allow a fair bit of oxygen in) and whether or not there is any lining. Some amphorae have fitted lids; in Portugal’s Alentejo lids aren’t common, but a covering keeps flies out, and sometimes a thin layer of olive oil is used to protect the wine.

As well as amphorae, ceramic spherical vessels made by Clayver are getting popular: these allow very little oxygen in. And there are small 200 litre clay pots with a small bung hole at the top made in France that are found in some cellars.

Glass

Finally, not made of clay, we have the glass lightbulb-like vessels that are made in Burgundy that have just emerged, and represent another option for fermentation or ageing. And, more traditionally, glass demijohns, used for smaller volumes and famously used in Maury in the South of France for maturing sweet wines sitting out in the sunlight. Glass is inert and neutral, so any oxygen transmission will come from the way they are sealed.