Exploring Portugal’s Tejo wine region (1) an introduction

In this series of articles, published together, I’m going to be exploring the Tejo wine region in Portugal, which has recently undergone a lot of change.

The Tejo is a substantial wine region, and its 12 846 hectares of vines represent 8% of Portugal’s total vineyard area. Of these, some 2500 hectares are in the DOC area. On average, the region makes 68 million litres of wine each year, and the average yield is a healthy but not excessive 55 hl/ha. The Tejo DOC and IGP wines account for 30 million litres, up from 15 million a few years ago.

Until 2009 this region was known as the Ribatejo. It has a long history of wine growing, but wine has been integrated into other forms of agriculture here: you don’t see wall-to-wall vineyards. Cereals, olives and cork are also part of the agricultural landscape.

The climate is warm and sunny, and typically Mediterranean in style, with long hot summers and most of the rainfall occurring outside the growing season. There are 2800 hours of sun a year, and precipitation averages 750 mm per year, with more in the higher-up north of the region.

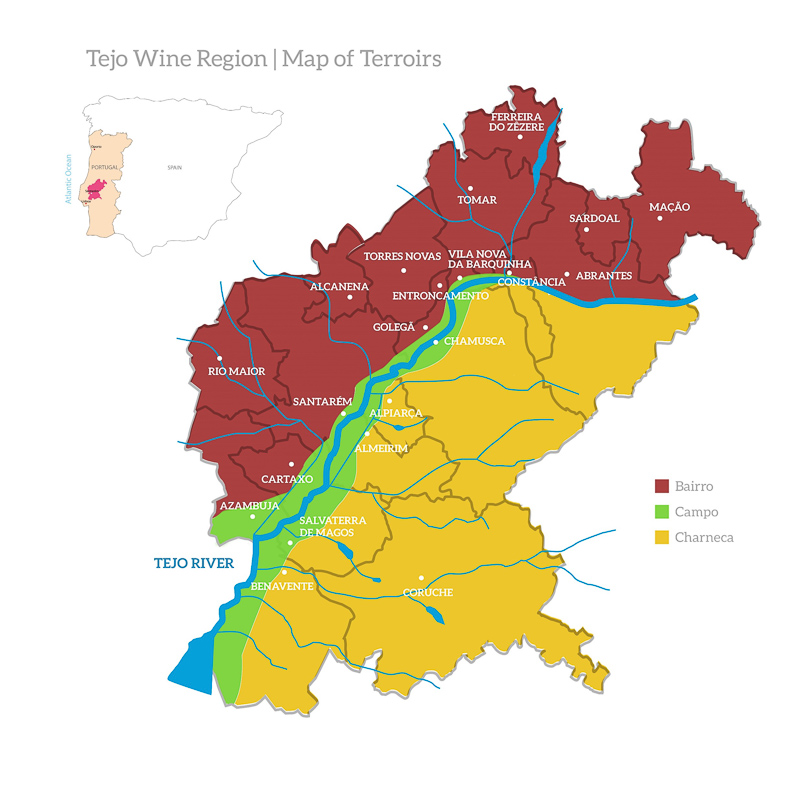

The river defines the region (pictured top and above), running diagonally from northeast to southwest and cutting it neatly in two. It’s a big river, and it affects the climate, moderating the summer highs, particularly in areas close to its flow. To the north we have the large terroir called Bairro, which is slightly higher up and has rolling hills, with interesting soils. Bairro is Portuguese for clay, which predominates, and there is even some clay/limestone here, but also a bit of schist right in the north. The Campo is the area either side of the river, and this varies in width, getting narrower further north. The soils here are well drained alluvial soils, and this is also a cooler area because of the proximity of the river. Then to the south of the river we have a terroir known as Charneca, which is a warm, dry subregion with predominantly sandy soils, although there are also some stony parts with river pebbles of varying sizes. But each of these broad-brush terroirs has many different micro terroirs. Irrigation isn’t the norm in this region.

So, grape varieties. Tejo has had a flirtation with international varieties, but still remains committed to Portuguese grapes. ‘At the end of 80s beginning of the 90s the French grapes had an important role in changing the vineyards,’ says Nuno Rodrigues of Casal de Coelheiro, one of the region’s leading producers. ‘50 years ago all the vineyards were on Campo, with richer soils.’ But many of them have been pulled out and these soils are now dedicated to maize, corn, wheat and peas. It’s the sandy soils that have been reserved for the vineyards.

‘People abandoned some grapes but introduced others, and the French grapes played an important role,’ he says. He’s choosing to focus on Portuguese grapes, and this year is planting two new ones: Alfrocheiro and Tinta Miuda. One of the reasons for the latter is because he’s learning to live with climate change: it is drought and heat resistant.

70% of the vineyards are white, and of this, around 60-70% is Fernão Pires. There were five monovariety Fernão Pires on sale five years ago: now there are more than 30. It can come in lots of styles. The traditional style was to use it to make a skin-fermented orange wine.

The recent journey of the Tejo region has been transitioning from a bulk producer to making wines that the modern market wants. In the past it made mainly cheap wine for the colonies, and then we have the era of the Junta Nacional do Vinho, part of Salazar’s Estado Novo, which was a government body that oversaw wine. A network of cooperatives made wine and stored it, controlling the market to iron out any price fluctuations. From 1930s to the 1950s they were particularly powerful, and the organization carried on until 1986 when it became the IVV.

Things have changed a lot. Tejo wines are still known for their value for money, but they come in a range of styles and price points, and are no longer just servicing the bottom end of the market. In this short report, I’m highlighting a few producers I visited, and also including notes on a wide range of wines tasted while in the region.

EXPLORING PORTUGAL’S TEJO REGION