Meeting Paul Hobbs and trying his wines: one of the world’s most accomplished consultant winemakers

One of the best known Californian consultant winemakers is Paul Hobbs. He began making wine at Mondavi in the late 1970s, and is now making his own wines from various corners of the world, including Argentina, France, California and New York State. I caught up with him to try through some of his wines, and ask him about his journey as a winemaker.

Jamie Goode (JG): Paul, how did it all start?

Paul Hobbs (PH): My first experience was at Robert Mondavi. That’s where my apprenticeship was. This was in 1977 as an intern and then 1978 full time. In fact, I didn’t start as a winemaker: I started working as a lab tech. And Mondavi had a research department, and I was the sous chef in the research department, so to speak. That was during my internship in 1977. But I also did double duty. I joined the maintenance department and worked two shifts. I wanted to get experience with winery equipment. Then I did a stint in the cellar, and this was all done within a 12 month period. By 1979 I was promoted to enologist, and shortly after that Mr Mondavi appointed me to the Opus One inaugural winemaking team. It was a small team and a small project back then, but it had great weight.

JG: I guess this was an important time for Napa.

PH: It was. We’d had the Judgement of Paris just before then. Actually, to be frank, I was not intending to stay in the wine business. I wanted to go on to medical school. If it hadn’t been for Opus One I wouldn’t be making wine today. It cemented my interest.

JG: What was Mr Mondavi like?

PH: He was outgoing, inclusive and a pretty warm personality. He was charismatic. I found him also to be egalitarian: it didn’t matter what your rank was in a tasting, which is something that was good for me because I was a junior.

JG: Was he important for the development of Napa?

PH: Extremely. He accelerated the whole region. He wasn’t only promoting his wines, he promoted Napa as much as his own wines. The Mondavi winery was a training ground for other winemakers. You had Mike Grgich who started Grgich Hills, and Warren Winiarski who started Stags Leap. Zelma Long, myself. It was a very good education.

JG: How long were you there at Opus One?

PH: I was at Mondavi seven years, six years at Opus. Then I left. I was approached by Simi Winery in Healdsburg, and they wanted to offer a new Cabernet program. They felt I was the proper candidate. It as after the 1984 vintage they approached me. After three of four months I said I’d give it a go. At Opus One I felt that I was up against a glass ceiling. Tim Mondavi, Robert’s younger son, was always going to be the head. I decided it was time to move on. I joined Simi and then we became part of LVMH. At the same time we invited a consultant from France to work with me on the Cabernet program, Michel Rolland. This was his first international consultancy, and I think the first work that he’d done outside Bordeaux.

JG: What was it like working with him?

PH: Quite different. Michel was new to consulting. He was very affable and loved blending, but he didn’t seem to have a lot of interest in how the wine got there. The wine is here and he’d spend two days blending. I was hoping that he’d bring more from a viticultural point of view, and talk more about the winemaking process. His passion is blending, and he’s very good at it. He’s a very fun person. I became an officer of Simi winey and I thought that would be a good thing for my career, but under the environment I was in at the time I was more of an executive and administrator, and lost my time in the kitchen. I was mid-30s and looking for how to further my career and gain independence. I decided to start looking for a way to start my own business. Paul Hobbs winery started in 1991. I didn’t have the capital that is required to buy vineyards or build a winery from scratch. This led me to a period in my career that was rather unsettled, but also dynamic.

Essentially, I went to Chile first, thinking this was an exciting upcoming region. This was 1988. But for various reasons I ended up being disinvited by my host because I had invited an Argentine. There were bad relations between Argentina and Chile in those days. Also, Pinochet was still in power in Chile. My host was very unhappy that I invited an Argentine, and the Argentine wouldn’t leave – his name was Jorge Catena, Nicolas’ younger brother. So we drove over the mountains on a Friday morning, I saw the first vineyards, and we drove to the Catena winery, which was called Esmerelda, and tasted some of the worst wines I’ve ever tasted in my life. This cemented what was commonly known, that Argentina was a country that consumed vast amounts of wine, but the wine was plonk. It was remarkable they could drink it. Then I met Nicolas Catena on Saturday.

JG: Who were you in Chile with?

PH: I was with Marcelo Kogan, who is not a wine maker. He was a professor at the University of Santiago, the Catholic University. I went to school with Jorge Catena and brought him because we were friends, and he spoke English and I didn’t speak Spanish. I thought it would be fun to hang out with him. There was nothing malicious about bringing him over: I just didn’t realise the sensibilities. Jorge had been sent by his brother to bring me back to Argentina, which is one of the reasons he refused to leave when I asked him to leave because of the situation with my host. Nicolas told me he had been struggling over 10 years to make wines for the international market. This led to an agreement between the two of us that I would come back and advise his team, which I did in 1989. At the same time, I told him he couldn’t mention it. But he did, and it was reported two months later in the Buenos Aires Herald that I was work with Catena, which was a problem because Chandon had their second largest winery outside France in Argentina. So I made an agreement with Nicolas that he would help fund the Paul Hobbs winery and so he became an investor. We began working on this in 1990. The deal I made with him is that I would run this program for him, so I was the architect of that, even down to putting the Catena name on the label. He resisted strongly. He wanted his father or his grandfather and one of those old Gallo-like labels like Carlo Rossi. Then I built Alamos, which became the launch vehicle for Malbec. There is quite a story behind that. All this time I was also consulting to help finance things, but I also found it quite interesting. My first domestic client was in 1990 with Peter Michael and shortly after that Swanson Vineyards. Then I grew a broad client base. Catena I had exclusivity with, but he did allow me to consult with another winery, Bianchi. In 1992 I also started consulting in Chile for Valdivieso. I had up to 35 clients per year. I left Catena to start Viña Cobos. The last vintage I made for Catena was 1997. I built the whole portfolio for Catena, even the naming. He named Catena Zapata, the top wine. The reasons for my leaving had to do with another problem I had with Nicolas. I was the importer for Alamos in the USA. It is a very detailed story, but essentially he didn’t want Malbec under the Catena name, initially. He didn’t want to produce Malbec. We were making Chardonnay and he was focused on that. But his importer, Billington Imports out of Springfield, Virginia, wanted a red, not just a white. So we cobbled together a Cabernet. I wasn’t happy with it, and it failed. By the same time I was making Malbec from a vineyard that I thought was really choice, but the way it was being grown would never have made good wine so we had to change the farming and make wine from it. Nicolas wouldn’t supply the barrels so I had to find my own way to get the barrels. Finally, when the US press came in March 1993 for the launch of the Chardonnay, this is when I showed them the Malbec. There was an article by Tom Stockley in the Seattle Times, Don’t cry for me Argentina. He mentioned the Malbec, and that got syndicated, and this fit Billington’s desire for a red. The Cabernet wasn’t working. But Nicolas said I’m not going to put Cabernet under the Catena name, it’s too risky. So we launched a new label, Alamos, and I became the importer. I did the initial seed work to introduced Malbec into the American market. Then when Catena saw the success he put Malbec under the Catena label.

JG: It sounds like an uncomfortable relationship.

PH: There were times where the relationship was really good and times where it was disruptive. Basically, I had an agreement with Nicolas that if I could sell 25 000 cases of Alamos in two years, then he would give me the Catena brand. That is the way I agreed that I would start an import company. I had no experience in importing wine, and certainly not in introducing an unknown variety from a new place. I beat the target, but didn’t get Catena. I got $100 000 and he pulled the brand, and I shuttered my import company. So I started my own company. It was just a difficult start. The company almost collapsed because it was so tough in the first four years, but then there was a political shift in Argentina, and when it finally settled down they decoupled the dollar from the peso, so everything was now a quarter of what it cost before. Financially it saved us, and we had good weather, and Viña Cobos grew.

Because of my work in Argentina, news started to spread. I was approached by one of the leading producers in Cahors, Bertrand Vigouroux. He came to Argentina and met with a Frenchman there, Fabre Montmayou, and put me in touch. Bertrand asked if I would come to Cahors, which I did in 2009. He immediately wanted to a business together. I told him I’d rather date for a while. So we did. Then we began producing wine together in 2011 under the name Crocus.

Then I was approached by Armenian brothers from the Los Angeles area, and they wanted to do something in Armenia. All these things are tied to unrelated situations. I remember when I was consulting to Stag’s Leap Wine Cellars, and Warren was stepping down, he wanted to celebrate all the winemakers who had helped him. I’d never been the winemaker but he invited me anyway. At the end of the celebration he made us put our hand print on the wall. But he also gave us a silver vial with two pips with Vitis sylvestris and Armenia, saying these are from the birthplace of wine. I put this away, never thinking this would mean anything, but then this happened and I thought this is fortuitous and I have to take a look. So I got started in Armenia. Spain came along about the same time, in Galicia. Visiting this was compelling as well so I couldn’t help myself. Finally, New York came calling. In 2011 I started working in New York and by 2014 I found the land that I thought would make top Riesling in Lake Seneca where the slopes are steep and you have shale and slate.

THE WINES

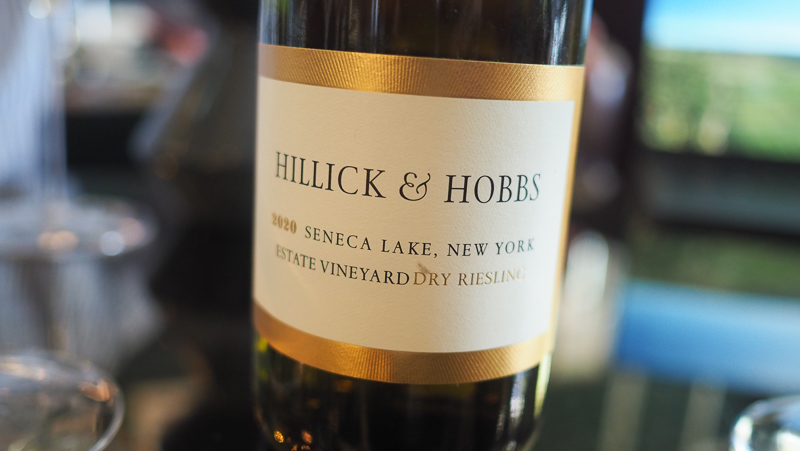

Hillick & Hobbs Dry Riesling Seneca Lake 2020 Finger Lakes, New York State

12.5% alcohol. 75 acre site, 22 acres planted, with the potential for 47 acres under vine. The vineyard is planted the way that the Romans planted the Mosel, on slopes, with slate soils. Planted on the fall line. It’s a much more expensive way to plant. The advantage is the row doesn’t block the flow of air or water and this has reduced the use of pesticides by two thirds. First commercial vintage was 2019. Lovely precision here with fine lime, lemon and honey. So precise with lovely texture, this is dry and focused, showing good concentration and weight. Very fine and mineral. 94/100

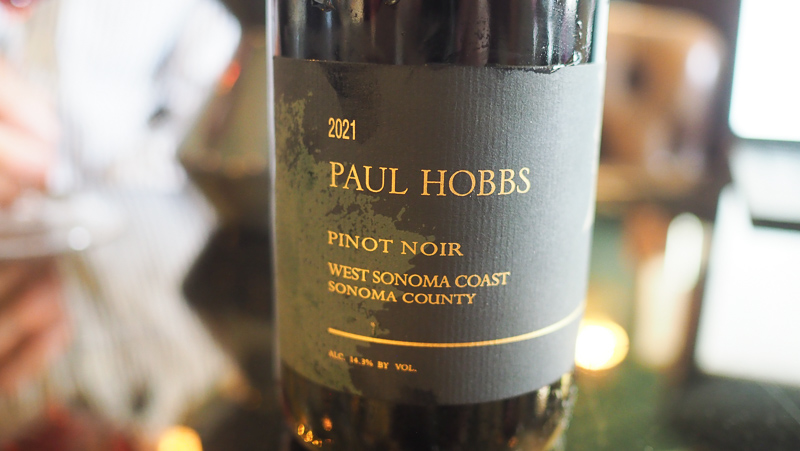

Paul Hobbs Pinot Noir 2021 West Sonoma Coast

This comes from a vineyard in Annapolis, five miles from the sea, with Goldridge soils. 15-20% whole cluster, most in small 3 ton fermenters. Aged in one-third new oak, with some 500 litre barrels. Concentrated and fleshy with bold, ripe cherry fruit, showing nice brightness. Lots of fruit here with freshness and energy as well as depth of fruit. Lovely depth and focus here with a finesse as well as concentration. A vivid, rich expression of Pinot. 95/100

Coombsville Cabernet

Paul Hobbs has vineyards in a very interesting Napa AVA called Coombsville, which is close to Carneros. ‘This is a cooler sub AVA and the grapes are picked in October,’ says Paul. ‘I’m just looking for balance as it relates to me. We walk the vineyard and make the harvest decision without doing any analysis. Top sushi chefs in the market don’t do any analysis, they just know. After 10 000 hours you just know, you have the intuition, if you have been paying attention.’ The soils here are volcanic, with igneous rock and compacted ash. He bought the vineyard in December 2012 but he’d worked with it for 5 years prior to the purchase. It was largely planted to Merlot, because people thought it was too cool to ripen Cabernet Sauvignon. As well as making his own wine from this vineyard, he also sells 3 tons at $25 000 each.

Paul Hobbs Cabernet Sauvignon Coombsville 2019 Napa Valley, California

20 months, with 69% new oak. Fresh, concentrated and sweetly fruited with blackcurrant, cherries and fine spices. Ripe and lush but showing lovely freshness and elegance. There’s a lovely chalky, grainy character here under the fruit, which shows lovely flesh and balance. There’s no over-ripe character. Picking at 25.5 Brix but the alcohol (14.8%) doesn’t stick out. Lovely balance to this wine with the oak perfectly integrated. 95/100

Paul Hobbs Cabernet Sauvignon Nathan Coombs Estate 2019 Napa Valley, California

This is from the very top blocks. 96% new oak. Great concentration here with pure blackcurrant fruit as well as good structure. There’s some gravel and ash, with a nice grainy mineral character and some spice and a hint of earth. But the focus is on the lovely fleshy blackcurrant fruit. Refined and pure. 96/100

Paul Hobbs Cabernet Sauvignon Nathan Coombs Estate 2014 Napa Valley, California

This is fleshy and ripe with sweet blackcurrant fruit and some grainy structure. There’s some ashiness here with a bit of gravel and chalk, and some nice sweet, lush fruit. It’s starting to soften a bit, but still has lots of fruit and some structure. Impressive stuff. 94/100

Crocus La Calcifère Malbec de Cahors 2018 Southwest France

Polished and refined, but also fresh, with fleshy black cherry and blackcurrant fruit, with some nice grippy structure under the fruit. Very focused and pure with smooth edges to the bright black fruits, showing nice freshness and weight. I really like the mouthfeel here, with the limestone making its presence felt in the fresh acid line. 95/100

Viña Cobos Bramare Malbec 2021 Uco Valley, Mendoza

Own 70 hectares of vines in different areas (four vineyards), plus they buy grapes. This one is mostly grower fruit. Lovely concentration here with a chalky edge to the fresh blackberry and blackcurrant fruit, backed up by some spicy detail. Lovely weight here. Crunchy, rich, lovely flesh but also some bones. 93/100

Viña Cobos Vinculum Chardonnay 2022 Mendoza, Argentina

There’s a competition among the growers to make it into this Vinculum line of wines. Nice concentration here with fresh citrus fruit. There’s a lightness despite the concentration with subtle meal and toast, and fine lemon and peach notes. Expressive. 92/100

Viña Cobos Vinculum Malbec 2019 Mendoza, Argentina

Nice concentration here with an appealing spicy edge to the ripe blackcurrant and cherry fruit. Has a slight bitter twist that’s actually quite pleasant, adding a sense of freshness to the lush fruit. Very fine. 94/100

Viña Cobos Hobbs Estate Malbec 2020 Perdriel, Mendoza

Old vines, up to 90 years old. Concentrated, intense, lush black fruits with some sour cherry and cocoa spice, as well as some floral notes. Very stylish and intense with a saline twist. Real density and lushness here: an impressive wine. 95/100

Viña Cobos Hobbs Estate Cabernet Sauvignon 2019 Perdriel, Mendoza

Lovely blackcurrant fruit here, with a sweet core. Fleshy and rich, with nice acidity and some very subtle green hints. Some olive savouriness and good structure, with beautiful fruit. 95/100

Find these wines with wine-searcher.com

UK agent: Alliance Wine