In the Swartland with Eben Sadie (1): the vineyard

Over the last 20 years (first vintage 2000), Eben Sadie has established himself as one of South Africa’s leading winegrowers. [You can read his story from this interview I did with him in 2012.] In November 2019, Ring and I visited him at his farm in the Paardeberg, in South Africa’s Swartland. We began with a viticultural masterclass walking in his home vineyard of Aprilskloof in the Paardeberg as he discussed his approach to farming.

One of the big shifts for Eben over the past three years is that he has been a vineyard owner. He’s always been interested in viticulture and has farmed all but one of the vineyards he buys from, but this has been a new step. I asked him: what have you learned about viticulture?

‘You can’t do it on your own,’ he replied. ‘This is maybe the most significant thing. I have learned much in the three years that I have been owning vineyards. It has been wonderful to work with great people who take the time to teach me. We all think we are great farmers, but it’s one thing thinking you are good at it, but there are a thousand things we can do better.’

One major theme for him has been climate change. ‘It has been a major topic. There are definitely areas in the world that are more prone to be affected. Look at areas in Australia, and here in the Swartland. These places that are already warm and dry will be the first to face the full wrath of the storm.’ He reckons that the key thing in the light of climate change is to farm well to protect resources, and to be sustainable. ‘One of the reasons I love the Swartland is not the lack of water, but because it is not a vastly irrigated area,’ he says.

‘This vineyard isn’t irrigated and it was planted in the height of the drought,’ he says. ‘The biggest drought in a century. It is now four years old and it has only known the drought.’

One thing he is doing differently is planting the vineyards completely square, in a sort of grid, so there are no fixed rows. The vines are bush vines at low density. ‘The beauty of planting square is that you can cultivate in different directions,’ says Eben. This means that if he needs to put a tractor in the vineyard, it isn’t always going down the same row, compacting the soil.

He’s also moved away from pesticides and herbicides, but he says that stopping using herbicides is the most difficult step. ‘How do you control the competition from other plants in a dry climate? A weed is a desirable plant in an undesirable place. The best way to keep weeds out of the vineyard is to grow things you want in the vineyard.’

So he plants cover crops to compete with the weeds. ‘In the early stages of summer we use a quad bike to roll the weeds, to avoid compaction. It creates a criss-cross carpet. This brings the evaporation down. It also moderates the soil temperature which is good for plant growth and microlife. After the season, we put compost on top of this, and it’s a great seed bed.’ This year Eben planted triticale, barley, wheat, white and yellow mustard, lupins and fava beans.

Plantings are low density, which suits the warm climate. ‘There is a place for high density, but with our water and hydric stress it might not be the best option,’ he says. He’s also not a fan of trellises in the Swartland. ‘We’ve only been trellising for 100 years. I’m more inclined to trust the past 6900 years. If you put this on a trellis system in our climate it increases your foliage spread. The only thing you put up on plates like that is solar panels. You capture a lot of sun, a lot of energy. But you must do something with that energy. You need more water and nutrients. I don’t view this as sustainable over the long term.’

‘I have been to many great regenerative farming conferences,’ says Eben. ‘Farming the vine is one aspect, but the money is between the rows. You must farm your soil, your cover crops. I can’t produce all my compost myself, but I try to do as much as I can.’

‘Prune conservatively. Reduce your yield. If you put a massive yield on a vine you also put a massive strain on them.’ Anyone who has spent time with Eben knows that he is the king of the analogy: ‘A young vine is like a young person,’ he says. ‘It needs to still find the boundaries of life. It is sometimes a little too optimistic about its capabilities.’

A new step for Eben has been his natural spraying program. ‘It has been incredible to see how it has worked. This year has been very tough. Last year was an easy year from a disease perspective. You can farm here naturally, but this year we got scared. The disease pressure and humidity this year were out of this world. It was way out of the norm if you take the weather stations.’

We look at some of the vines. There’s some Garnacha Tintorea (Alicante Bouschet). ‘It’s a very resilient, powerful vine. We have three strains of Cinsault, three strains of Grenache, two strains of Carignan, and at the bottom we have Counoise and Terret Noir.’

‘I have another vineyard that I have just planted. It’s a white vineyard with Vermentino, Picpoul, Marsanne, Grenache Blanc, Cinsault Blanc, Grillo, Catarrato, Chenin and Assyrtiko. We have also planted Fiano, Aglianico and Agiogorgitiko, and Xinomavro. We are planting a lot of new varieties with the hope that they can also help.’

Eben explains that vines can be isohydric and non-isohydric. The former regulate their stomata well and deal well with warm conditions, while the latter just keep going, and consequently use more water. ‘We must plant isohydric vines. Non-isohydric vines is like that guy who at 2 o’clock in the morning is swinging on the chandeliers, partying it hard, going all out. But the next day you don’t see him until 4 in the afternoon. He’s not very productive as a person. Then you have that other friend who at 10 o’clock throws a ninja bomb and he’s out of there. You wake up and he’s done a marathon, he’s done the dishes and he’s made breakfast for everbody. That’s isohydric. Being realistic about tomorrow.’

‘I’m very proud of our viticulture,’ says Eben. ‘It has been an amazing few years. I had to design a lot of new tools, new machines, new policies. For me, the best thing about the drought has been that although it might have taken 30% of the last three crops, what we gained from the drought in knowledge and proactive farming is worth it.’

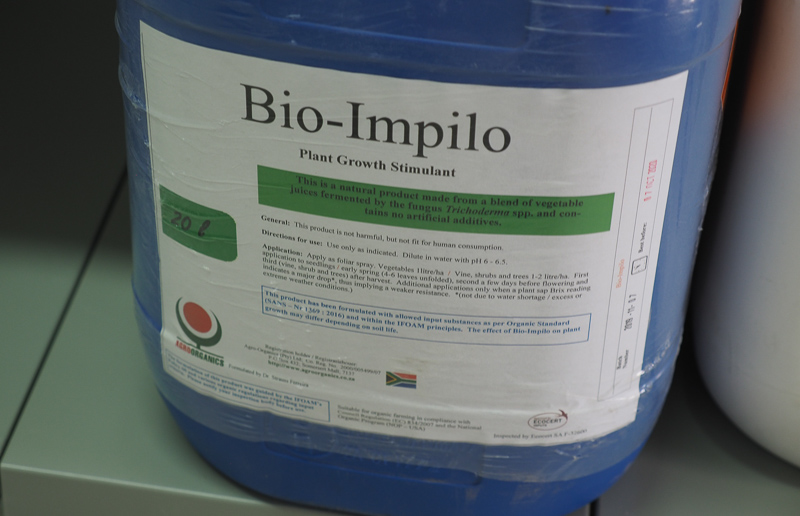

On pruning: ‘If you prune with a blunt pruning shear, instead of cutting the shoot is getting crushed and it bursts. That is where the infection is going in. When we prune we seal all our vines. We spray trichoderma.’ His philosophy is all about populating the vineyard with the right things. ‘The whole thing about organics and biodynamics or whatever you want to call it is populating the best population first. Don’t bother building and then not occupy the building: you will get bad tenants.’

One of his ideas is that leaf size affects disease susceptibility. ‘Big leaves are big disease receptors. Cinsault has big leaves. That’s why Pinot Noir and Chardonnay are planted in Burgundy: they have small leaves. They can handle the disease pressure. It’s not the only reason, but it’s a big reason. The reason Grenache isn’t planted north of Avignon is because it can’t flower north of Avignon: it is too wet.’

Eben talked through his spray program, which he days is very simple, mainly relying on sulfur and copper, which are the cornerstones of disease control in organic farming. ‘Copper is a big topic,’ he says. ‘If you use too much you have copper toxicity in your soil. These are the two big elements of any spray program. They are preventive. If you get in big trouble they are not going to work for you. They are very good.’

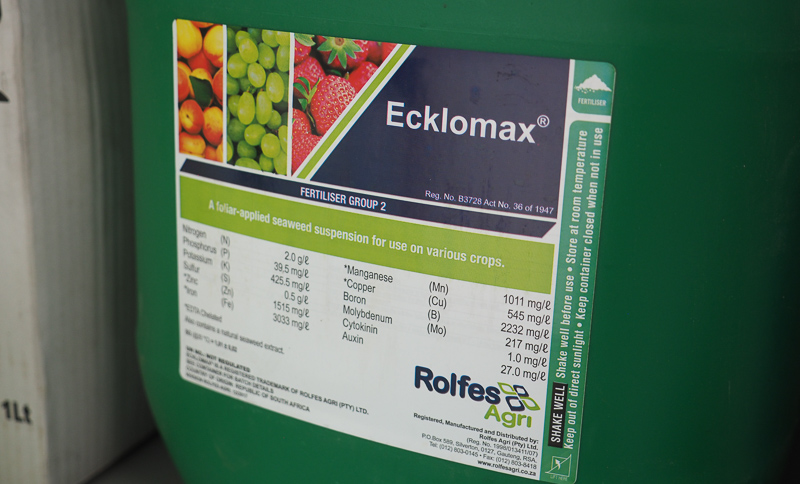

He also uses a range of other products. One is from Agro-Organics, called Bio-impilo. It is classified as a plant growth stimulant, but it is actually a metabolite that is a secondary product from Trichoderma, and it is antifungal. ‘It is a great fighter against downy mildew,’ says Eben. ‘Then we use seaweed fermentation, because you must boost the plants. We plant new vines in old vineyards and put a lot of environmental inoculants to get microbial life in the root zone.’

He also uses a range of Trichoderma preparations. And some of his sulfur applications are with sulfur dust. ‘Ssulfur dusting is largely underrated. It is the old school way. Some years we use this.’ He also uses a pine resin preparation in his sprays if rain is coming. ‘It keeps the spray longer on the leaves.’

‘Even in organics there is a compromise. It is not all square, there is always a bit of a backward pass. But it is probably the compromise that you can live with at this stage

This year I had a downy mildew outbreak. The only thing that bothers me about organics is you have to spray every seven days. Which means you are consuming more diesel and there is a lot of compaction.’