Olerasay No 2: a South African sweet wine that is becoming one of the world’s greats

Five years after the first release, we have Olerasay No 2, a solera-aged straw wine from Mullineux in South Africa’s Swartland region. The first release was amazing but this is better. It is in a peer group with the world’s best sweet wines.

‘In essence, Olerasay is a straw wine,’ says Chris Mullineux. ‘When we moved to the Swartland in 2007 we thought about what kind of wine we wanted to make here, and when it came to making a sweet wine, there are a few different options.’ Ice wine wasn’t an option in the Swartland, and they don’t have the humidity for botrytis to make noble late harvest. Late harvest is an option, but it’s hard to have the acid needed to balance the sweetness when you make a wine this way. ‘For us, straw wine was the obvious way to make a sweet wine in our climate.’

It all begins with viticulture. ‘There is not a great wine in the world that doesn’t start in the vineyards,’ says Andrea Mullineux. ‘It is the key to everything. In the Swartland we have war, dry, breezy conditions so there is very little disease pressure. We have tried to maintain the healthiest fruit at harvest. The ideal for us, is that in the winemaking process when we are air drying the grapes, we are concentrating the sugars and the flavours, and the most important thing, the acidity.’

They work mainly with old vineyards, and Olerasay is sourced from the same dry grown old vine Chenin that they use for their dry whites. They are looking for the grapes that have the most acidity at harvest. These are grown on the granite soils of the Paardeberg and the schist soils of Kasteelberg.

They are fortunate to work with old vines. ‘The secret to old vines is that they are in a natural balance,’ says Chris. ‘They have gone through drought, they have gone through contractions and expansions, and they have found a natural balance. They have learned how to deal with stressful environments and more vigorous environments. The yields tend to be lower so you get more natural concentration. Old vines have a huge impact in terms of the quality we are able to achieve.’

‘Bush vines are interesting for us,’ says Chris. ‘Being a warm dry climate we have a lot of sunshine, and there is a lot of light in the summer. We like to have a bit of shade: if you have grapes just standing in the sun you get a lot of tropical fruit flavours, whereas a little bit of shade works really well because you get more citrussy aromatics and a bit of flintiness in the wine. This makes the wine more complex. The structure of a bush vine helps to shade the grapes a bit. The canopy of the bush vine makes an umbrella that protects it from the sun.’

They capture freshness by harvesting at normal ripeness. ‘By harvesting them at normal ripeness, we are stopping the ripening process by cutting the grapes off the vine,’ says Andrea. ‘We are not losing the acidity in the drying process. One of the most important things is the shape of the bunch and the size of the berries. We don’t want bunches that are too compact, or too loose.’ They want healthy grapes through the drying process.

With late harvest wines the ripening process continues and acidity is lost as sweetness rises. It’s only really an option when you start out with very high levels of acidity, such as Riesling in the Mosel. With the straw wine concept, the acidity is maintained and even rises as the sweetness increases through drying.

‘Most straw wines around the world are dried indoors, because they are picking at the end of the season when there is rain,’ says Chris. ‘We are fortunate in the Swartland to be picking at the end of January or early February, so we still have two months of really great weather.’ So they dry the grapes outdoors under shade. They are one layer thick, and the process takes two to three weeks. Over this time the moisture evaporates and the grapes start to shrivel. This concentrates sugar, flavour and acidity.

‘In the vineyards we are normally getting 4-6 tons/hectare,’ says Andrea. ‘We usually get 70% recovery from that, so from every ton of grapes we get about 700 litres of juice. With the straw wine we get a 10% yield. So for every ton of grapes we only get about 100 litres of juice.’

Then it’s time to press. ‘It takes two days of long, slow pressing,’ says Andrea. They select from the juice: some is just too sweet, and sometimes not sweet enough. Press fractions are taken.

The juice is so viscous it can’t be settled. But because it is a long slow pressing, the juice is coming out fairly clear. It goes straight to barrel and there is a natural fermentation. This kicks in pretty quickly, even though the juice is very sweet. ‘A really strong yeast culture has built up on the grapes,’ says Andrea, ‘so they start fermenting within a couple of days.’ Then the fermentation takes up to 10 months: the fastest is 7 months. ‘We don’t stop the fermentation,’ she says. ‘For us it is important that it naturally stabilizes. To stop the fermentation you’d have to add a lot of sulfur dioxide, or freeze it, or sterile filter it.’ There are variations in the sugar, acid and alcohol each year, but it maintains the same ratio. In sweeter years the acid is higher, which is ideal.

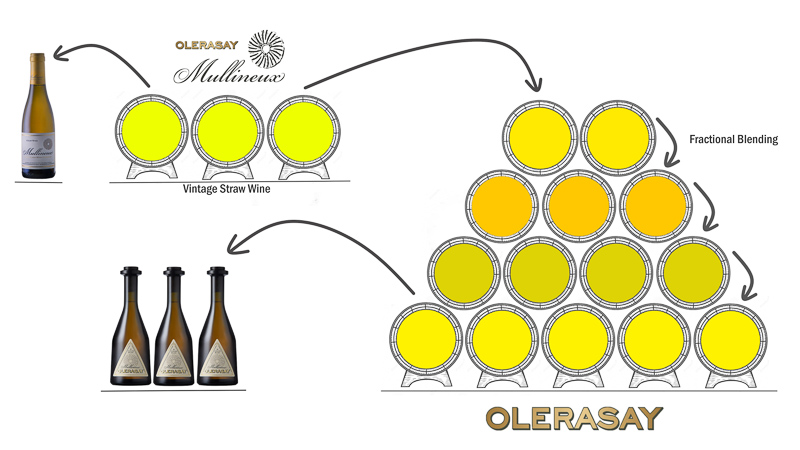

In the vintage straw wine they have one new barrel every year, but most are old. They leave the wine to be stable and then bottle a vintage straw wine every year, usually at vintage so they can fill them with the next wine straight away. These aren’t barrels you want to leave empty. Then they keep two barrels back, and these are the barrels that are used for the solera.

‘A solera is a fractional blending system,’ says Andrea. ‘The wine is ageing and becoming more complex. As the wine in the barrel ages, natural evaporation occurs, so wines need to be topped. This happens in most wines around the world. In that process of ageing the wine is concentrating the flavours, bringing so much more density to the wine. This is what makes the solera system exciting to us.’

The wine is also stabilizing. As the wine ages, it develops a dark amber colour. But anything that can drop out, including the amber colour, will drop out in this ageing process. When the new vintage of wine is added to the solera, it brings it back to life. ‘This solera, which spans the 2008 to 2019 vintages, tastes younger than any of the individual vintages did on release,’ says Andrea. ‘This is the beauty of the solera system.’

One of the benefits of this long stabilization is that the wine is, in Andrea’s words, bulletproof. It doesn’t deteriorate after opening in the way that most wines do.

The first Olerasay, the primero, was 2008-2014. This is the second release, and contains wines from 2008 until 2019.

‘In theory, you can release one every year,’ says Andrea. ‘But we wanted to wait until it was significantly different, and significantly more concentrated and complex, not just from our vintage straw wine, but now comparing it with our first release of Olerasay.’

They don’t bottle the whole solera, because they wanted to build it again: they bottled part for number one, and part for number two. The idea is that the wine becomes more complex with each release. The solera was 16 barrels and they have bottled about half of it this time: the barrels are blended in a tank and then they bottle from there. Both releases of Olerasay have been just under 6000 bottles.

Solera is a protected name that they can’t use, hence Olerasay is their chosen name.

Olerasay 2 Chenin Blanc NV Swartland, South Africa

8.5% alcohol. A deep gold colour, this is viscous and intense. The nose is honeyed and mellow with some tropical fruit notes, fresh table grapes and a hint of raisin, as well as some spice. The palate is fresh and intense, and multi-layered with lovely lemony acidity countering the intense apple, citrus, nectarine and cantelop melon notes. There’s some grapey richness and just a hint of raisin. It’s astonishingly concentrated and multidimensional, with so much complexity and density. A little sip goes a long way: there are so many layers of flavour, and an almost perfect balance between the sweetness (which is intense) and the acidity. 97/100

Find this wine with wine-searcher.com