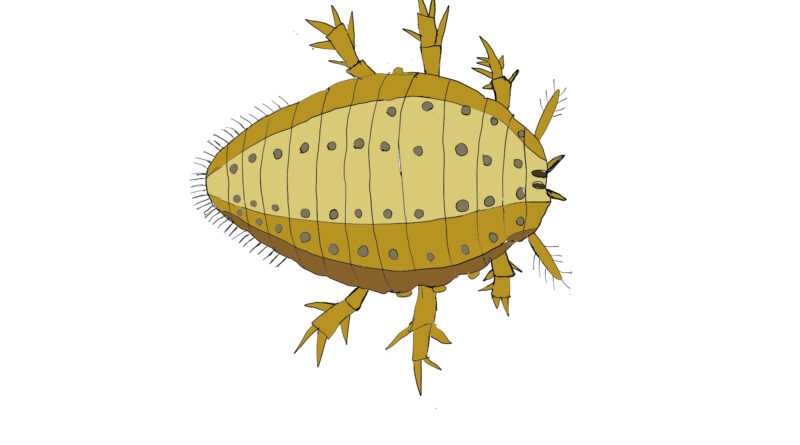

Introducing phylloxera, the aphid that changed the face of wine

The implications of the phylloxera crisis, which almost wiped out wine as we know it, are still being felt today. Jamie Goode introduces the 19th century epidemic caused by a small yellow aphid.

Biosecurity is a big thing these days. Get off a long-haul flight with an apple in your hand luggage and you could end up with a hefty fine if you forget to dump it before you reach customs. Back in the 19th century, though, it didn’t exist. People moved plants – and with them associated pests and diseases – all over the world.

It was the lack of realization of the importance of biosecurity, coupled with the arrival of the steamship, that almost led to the elimination of wine as we know it. Why the steamship? It meant that plants shipped from one continent to another would arrive quickly enough that any associated pests would stand a much better chance of surviving the journey.

Enter phylloxera. This is an aphid that feeds on the roots of vines, hailing from North America. Depending on the strain and the location, it can also feed on leaves. Here, it coevolved with the native vines and the two grew alongside each other without too much trouble. Good parasites don’t kill their hosts: after all, they need somewhere to live. They take a little, but not too much. But Vitis vinifera, the Eurasian grape vine species that is the basis of most of the wine made worldwide, has evolved in the absence of this aphid, and when the two came together it was an unbalanced relationship that caused the death of the vine.

How did phylloxera find its way to Europe, and from here to the rest of the world? The answer lies in another disease that shook the wine world: powdery mildew. This also came from the USA, arriving in the 1850s. Here also, native American vines show resistance to this fungal disease, but when it arrived in Europe, Vitis vinifera was highly susceptible. One proposed solution was to try growing resistant American vines and so these were shipped to Europe. They brought with them phylloxera.

The earliest outbreaks were recorded in the 1860s in the Southern Rhône and the Douro, and then shortly after in Austria. From the initial incidences, the spread was rapid, and the latter part of the 19th century saw phylloxera spread through much of the wine growing world, leaving a trail of economic devastation.

Modern genetic studies have shown that there were likely two independent outbreaks of phylloxera that then spread to most corners of the wine world. The first – and most widely documented case – was in the south of France, and the second was in a nursery in Austria. By the time people realised what was going on, infected plant material had already widely spread from these two locations by viticulturists looking for a cure for powdery mildew.

The life cycle of this insect is complicated, but the damage it causes very real. As it sucks from the undefended roots, their vascular system is disrupted and they slowly stop working. The vine begins a decline that results a few seasons later in death. It’s also thought that the feeding damage also opens the roots up to infections, which hasten the vine’s demise.

It is hard to imagine the panic that must have been felt at the time in wine-producing countries such as France, where this drink was such a part of the culture and the economy. At the time, one-sixth of France’s state revenues were generated by wine and one-third of the workforce derived a living from it.

It was down to Professor Jules-Émile Planchon, a botanist appointed by the government commission established to investigate the outbreak, to identify the culprit. He dug up roots of a healthy vine and observed clumps of minute wingless insects happily gorging themselves.

Phylloxera has a complicated life cycle, which was only worked out after the plague had broken. Like many aphids, it is parthenogenetic, which means it doesn’t need sex to reproduce. The root-growing form settles on suitable roots and punctures them with its mouthparts. It injects saliva, and this causes the root cells to grow into a structure known as a gall, which increases the supply of nutrients and provides it with some protection. Then it lays eggs, which hatch, and the resulting winged versions of the aphid move along the roots, climbs the trunk and are blown into the air. If they find a suitable feeding site they’ll carry on proliferating, and populations can increase rapidly. In some regions there are asexual forms of phylloxera that can develop on the leaves. These also induce gall formation, and in this case the protective structure that encloses the feeding phylloxera extends below the leaf and opens to the upper leaf surface to allow crawlers out.

Lots of solutions were tried. Chemical defences were tried and largely failed (a nasty insecticide called carbon bisulfide had some effect when injected into the root zone, but this was limited); flooding vineyards in the dormant period seemed to work; and vines growing in sandy soils were unaffected. But for most vineyards that weren’t sandy and which couldn’t be flooded, there was little hope.

One controversial solution was proposed. American vine species, which harbored the invader in the first place, had natural protection against phylloxera. Where they had been planted they thrived, while all around them was a scene of devastation. Yes, the wine they produced tasted fairly bad but better odd wine than no wine at all, argued the faction supporting this approach, which became known as the américainistes. Tastings of wines made using the American vines were set up, but the depressing conclusion was that these wines, with their unusual tastes, paled in comparison with what people were used to from the vinifera varieties.

But what about crosses between American vine species and vinifera? Would these combine the resistance of the former with the wine quality of the latter? This was investigated in a flurry of breeding efforts which resulted in what are now known as the French-American hybrids. Some of them are actually pretty interesting varieties, but they vary in their resistance to phylloxera, and never really caught on all that much. Still, this was a very interesting period for vine breeding.

Then, someone had a brilliant idea. In 1869, a Monsieur Gaston Bazille suggested grafting vinifera varieties onto American rootstock. With the benefit of hindsight, this seems an excellent solution, but at the time there were many unknowns. Chief among these were the following. First, how long would the graft last? Second, would the rootstock impart some of that American vine character to the wine, altering the qualities of the vinifera variety by this unnatural union of scion and stock? And third, how resistant would the various rootstocks be? It was already known that some American vines were more resistant to phylloxera than others.

One of the first documented applications of this grafting was in 1874, when Henri Bouschet displayed an Aramon (Vitis vinifera) vine grafted onto American rootstock at a Congrès Viticole in Montpellier. In a short time it became clear that, somewhat counterintuitively, the wine made from vinifera vines grafted onto American rootstocks retained the full character of the vinifera variety while benefiting from the phylloxera resistance of the American roots. It completed a rather neat circle. The plague had come from America, but so had the salvation.

The idea spread. The technique of grafting was easy enough to learn that just about anyone could attempt it. The supply of American vines was more of a problem, because many wine regions began to prohibit their importation in order to prevent the remaining phylloxera-free vineyards from succumbing to the pest. However, not everyone was won over by this radical idea of grafting. Many resisted replanting, with the attendant three-year loss of production, and clung tenaciously to their chemical treatments. In the end, good sense prevailed and the grafters won the day. The lengthy work of replanting phylloxera-devastated vineyards began. It was not a straightforward process, and some of the grander estates, reluctant to pull out their vines kept them going with insecticide treatments as long as they could. The choice of appropriate grafting material was also complicated by the fact that it took a while to find American vine species that were well adapted to the chalky soils that predominated in some of France’s key regions.

The implications of the phylloxera crisis are still being felt today. The main effect was the change of the viticultural landscape. Taking France as an example, vineyard area reduced quite significantly. The replanting also meant that there was a sort of viticultural bottle neck, with many traditional varieties losing out and getting forgotten in favour of more commercially interesting ones. [Currently, in many regions people are looking to reintroduce ‘lost’ varieties that ended up losing out during this phase of replanting.] One of the traditional ways of planting vineyards, called layering or marcottage, which involves putting a still-attached cane in the ground so that it grows its own roots while relying on the mother vine, and eventually becomes a separate vine in its own right, is no longer a sensible option. This is because the roots will be vinifera and thus susceptible to phylloxera. Pre-crisis, many vineyards were planted en foule – essentially randomly without rows – because of the continued laying down of canes and even trunks – continually regenerating the vineyard without wholescale replanting. Post-crisis, most vineyards were planted in rows.

In addition, the choice of rootstock, with its effect on graft parameters, such as vigor, became an additional variable, and a new item in the viticultural toolbox.

Some areas have escaped phylloxera, and there you can still find vines planted on their own roots. Most famous of these are Chile and South Australia, which have stayed free of the plague. Argentina and Washington State also have largely ungrafted vineyards, and while phylloxera is present in both, it doesn’t seem to be a major problem. This could be because of the soil structure, and in Argentina’s case some have suggested it is because much of the irrigation is through periodic flooding. In Germany’s Mosel wine region there are still many ungrafted vines (again, the soil seems to be protective), and the Douro has a famous vineyard planted on its own roots: Quinta do Noval’s Nacional. In New Zealand’s Central Otago wine region the oldest vineyards there, dating back to the 1980s, are ungrafted (some are succumbing, alas), and some of Oregon’s older vineyards are on their own roots (likewise, they are suffering).

So, for the last 130 odd years there has been a truce. Through grafting onto American rootstocks we have wine, still, more or less as it used to be. The roots and the aphid live together in a sort of balance. For the future? What would happen if this balance should become unsettled, and a new variant of phylloxera develop that ends up killing the vine? The thought is pretty much unthinkable.