What can wine critics learn from music reviewers? Geoffrey Moss interviews Peyton Thomas

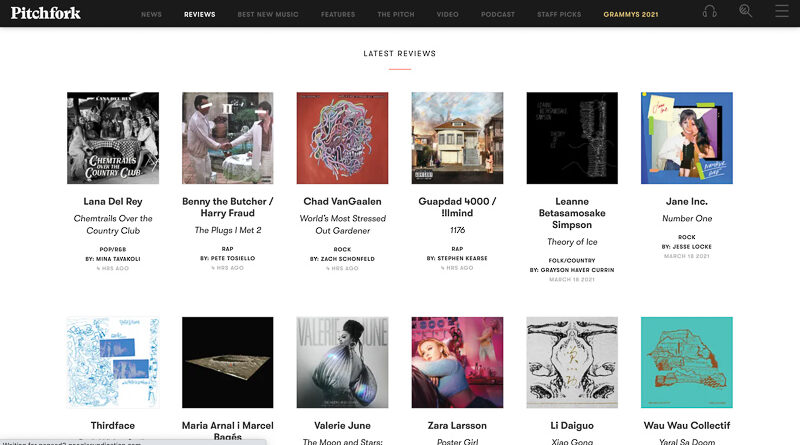

Geoffrey Moss is a Master of Wine based in British Columbia’s Okanagan Valley, where he is a contributor at Gismondi on Wine and runs a wine consulting business. Here he interviews Peyton Thomas, a Toronto-based freelance journalist and contributor at Pitchfork, looking at parallels between critics working in music and wine. You can read Peyton’s writing and learn more about his upcoming novel at peytonthomas.ca.

Geoffrey:

How do you go through the process of reviewing a new album?

Peyton:

I don’t know if many people know this actually, but music reviewers do generally get the album at least a few weeks in advance, sometimes many months, to give us time to listen to it and live with it. That can definitely vary if an album is a surprise drop, and critics don’t get it until it’s out. Then you usually only have a few days. But generally, I have at least a few weeks.

So, what I like to do is listen to it a few times while doing different activities. Sometimes just sitting and relaxing, sometimes walking around the neighborhood. But before I make any notes or form any opinions about it, I just like to get familiar with it through repeated listening. And then, after four or five listens, I will start to take notes on it.

Outside of the listening process, I’ll also research the artist and read any interviews that they’re doing in the lead-up to the release of the album. If they’re an established artist, then I’ll also listen to other albums in their catalog at least once or twice, just to really get familiar and build a base. And once I feel like I have a good base in place, I’m familiar with the album, I can talk about it casually with a friend, then I will start outlining my review, and I’ll go through a couple drafts before I send a presentable one to my editor at Pitchfork.

And then, we’ll go through a process. I’ll get some notes on the review. They’ll push me to go deeper. Sometimes the editor disagrees with me about the quality of the music, which is always interesting, and we’ll have to really work to justify my opinion.

But that’s the standard process, and it can vary depending on many factors. I know that may sound a little mechanical. But, because it’s so subjective and the approach I can take to the writing of the review itself can vary so widely, I like to just have a bedrock process in place.

Geoffrey:

That makes sense. When you’re listening to an album, how important is how you’re listening? Are you listening on certain headphones, certain speakers?

Peyton:

No, I probably should invest in some quality headphones, but I truly just listen on the little earbuds that come with the iPhone. I remember seeing an Instagram post by Lorde when she was working on her album Melodrama saying that every night she listened to the album on iPod headphones because she wanted to hear it the way her fans would hear it. So, not with sensitive studio equipment but with the standard equipment that most listeners use. So, I feel like I’m normal in that respect at least.

I find that I get the most out of an album if I’m in a context where I’m not paying attention to myself. Sometimes it’s walking around the neighborhood. Sometimes that’s doing chores or cleaning. Sometimes it’s just playing chess online. Just something that enables me to get in the zone a little bit and, lets the music seep in while I’m focused on something else. It’s a way of getting familiar with the music.

Geoffrey:

One of the reasons I ask about how you listen to the music is because there was a recent discussion on Wine Twitter talking about how certain critics are arguably reviewing wine incorrectly. It made me think, “Would someone reviewing another subject matter like music have that same criticism?”

Peyton:

The big thing about music is that the experience of listening to music is so different from a recording versus hearing it live. I would go to as many as 50 or 60 live shows a year in a normal year. So, I have really missed it during COVID. There was a recent album that I reviewed, Palberta’s Palberta5000. And, Palberta are a New York punk band, and they were branching into more traditional pop sounds on this album. And for them, that essentially meant there were a lot of songs that were just really solid pop hook, repeated over and over again.

And, listening to it, it was an incredibly dull listening experience sitting in my bedroom. But I could tell that some of these songs would be fantastic live as the tension builds and people bounced around. And, I tried to take that into account in my review, saying, “Palberta’s primarily a live band. I’m sure a lot of these would sound great live. The recording doesn’t really translate.”

Geoffrey:

And, I think that’s interesting how it contrasts to wine reviewing because typically if you’re a well-known wine critic, you’ll be tasting literally thousands of wines in a year. It could be 5,000, 10,000. And how you taste them is very analytical. You’re maybe spending somewhere between five to ten minutes a wine. When you’re tasting it, you’re spitting it out, because you can’t drink when you’re going through that many samples. And then you’re moving on to the next wine. I mean, there’s a couple potential issues with that. I mean, the first is you have palate fatigue over time. Can you really accurately analyze wines like that? I personally would say no.

But perhaps more importantly it’s very removed from how people actually enjoy and experience wine every day. It sounds like your process is much more closely aligned with how the average person would listen to an album. If I’m having wine at home, I’m having a glass of wine with dinner. I’m not having one or two ounces and quickly moving on to the next one.

Peyton:

I freelance for Pitchfork, so I will maybe write one to two reviews a month. So, the fatigue isn’t as much of an issue there. I’m able to spend a lot of time with each album, which I do appreciate.

But at the end of the year, I do get to vote on the year end list. And that is always a time when I wish I’d spent more time with more albums throughout the year so I was coming to the end of the year with a better perspective.

But it’s a time when I’ll go back and try to just listen to anything I missed in like a two week period. I need to get better about that because I do feel I missed things or the brilliance of certain things I’ve lost if I’m not spending enough time with it cramming it all into a period at the end of the year.

That’s also a time where I’ll have to set aside what I personally enjoy and spend the most time with versus what critically is important to the music of that year. If you add up the music that I listened to most last year, Dua Lipa and Taylor Swift would probably be up top because that’s what I listen to when I’m puttering around and working out.

But I wouldn’t say that either of those were the best album of the year, so I do take into account, like, “What did I listen to the most?” That’s the main factor, but then I also have to take into account craft and context and all kinds of other factors.

Geoffrey:

And so how do you account for those personal biases?

Peyton:

That becomes a factor at the end of the year when I’m making my vote for the best music of the year. I use this service called Last.fm, which keeps a record of everything I listen to. So I can actually go back and say, “Okay, which new albums did I listen to most this year? We have Phoebe Bridgers, Fiona Apple,” and I’ll make that list.

Then I’ll look through albums that my fellow critics at Pitchfork have ranked highly. I’ll look at Metacritic. I’ll look at a website called Rate Your Music, which tends to be more user and listener driven and pluck albums that seem to be standing out and then have a listen.

And I do as much reading as I can. I’ll talk to my fellow critics. Last year we had two rounds of voting, which was helpful because initially the list of albums was any album that came out this year. Then there was a short list of maybe 100, which let me kind of drill down and focus closer.

Geoffrey:

And then when you’re reviewing individual albums, are the albums that are assigned to you kind of within your wheelhouse in a sense? Are you only getting albums that fall within the genres you specialize in or have an interest in?

Peyton:

Oh, sure. I mean, I wouldn’t feel qualified to review a metal album, for instance. I just don’t have the familiarity with the genre. When I began writing for Pitchfork and I was asked “What sort of music do you want to review?” I did say: “I don’t think that I’m qualified to be a rap critic. I think those opportunities should go to Black critics not me.” I have written about rap for year-end lists, but I don’t want to take opportunities away from Black writers.

At Pitchfork, every couple weeks they’ll send out a list of upcoming albums that need to be claimed and you can put your hat in the ring to review an album. Assignments are handed out that way.

Occasionally, an editor will reach out to me directly asking if I want to take on a certain album, and I can say yes or no. But generally I mostly review albums in the indie-rock space. So, it’s pretty narrow, and I’m making little efforts to branch out beyond that. But the year-end list, I consider everything across all genres

Geoffrey:

When it comes to wine critics, typically there’s not a lot of specialization. There’s some, but it’s quite general. Obviously every critic has their own personal biases. So there seems to be two broad approaches. The first approach is just to let the bias come through in the review and that’s part of the reviewer’s perspective. Then the other approach would be to attempt to treat the wine very objectively. It’s like “Okay, I don’t like this particular grape variety. But from the standpoint of this particular grape variety, this wine’s quite good” or quite poor whatever the case may be.

Peyton:

I mean, in the case of wine, we are literally talking about taste, right? And even on a personal, biological level, people can process taste very differently. I’m thinking about cilantro and how some people just process the taste of cilantro as soap.

With regards to music, but also with wine, I think it’s true that you can acquire taste and certainly a seasoned wine critic can appreciate differences more than someone coming to it. I really don’t drink. It all tastes the same to me, and the taste is not good.

When I first came to music criticism in a serious way, I was drafting a book proposal to the 33 1/3 series. Which is a series of short books. Each one is about a notable album, so I was very familiar with the album that I was writing about. But in researching and reading about it, I found that I was unfamiliar with a lot of the artists’ influences. I was unfamiliar with a lot of the other artists working at the same time that the artist was compared to.

So I embarked on a multi-year effort to listen to and make personal judgements about every album on the Rolling Stone’s 500 Best Albums of All Time list. It was a little arduous, and I don’t even necessarily know if I agree with the list. At least the version of the list I listened to was very, very biased towards dad rock. “We’re going to have 10 Springsteen albums here.” And I love Springsteen, but come on.

Then I began listening to Pitchfork’s Best of the 70s, 80s, 90s lists. And so that was just my primer for getting used to, in a very general way, to at least the most major work. It gave me some fluency in genres and time periods that I hadn’t known about. That was the way that I did my research.

But not with a guide to “Other people say this is good, therefore I must like it.” But definitely giving myself license to form opinions about it and say whether or not I enjoyed it personally. I think that was pretty vital in giving me like a base of knowledge that I could use to judge other music.

Geoffrey:

So would you say you made your way into music criticism through listening to a lot of music?

Peyton:

Yeah, absolutely. And in 2015 I started going to shows on a weekly basis and getting a feel for what I enjoyed in a show and what I enjoy in a live band. Like I said, I really miss it. COVID has been very hard.

Geoffrey:

But you don’t have a music background per se, as in you didn’t study music?

Peyton:

Oh, god no. I mean, I took piano lessons as a kid, but I really have no natural aptitude for it. I can tell you what instrument is on a recording, but I can’t tell you specifics about composition.

Usually in my reviews, I’ll focus more on songwriting, on culture and context. I can recognize good playing when I hear it. Like a good wine critic doesn’t need to have a good vineyard to know what tastes good necessarily. As long as you’re familiar with the basics of the process and I guess in the same way that a food critic doesn’t have to be a good chef.

Geoffrey:

I’m with you on that. And I feel like in the wine industry, that’s not as widely accepted.

There’s a lot of skepticism about wine critics in general. Especially if they come from a background with little experience in the industry. But I would say the value of that is they typically have a much stronger writing background. So, the pieces themselves are vastly more entertaining.

Peyton:

That’s especially true with music criticism. Being a talented artist in one area doesn’t necessarily mean being a talented artist in another area. So, I think I’m a pretty good writer; I cannot do music for shit. There are plenty of excellent musicians; writing may not be their forte. I think the purpose of music criticism is that your average listener will also not have the music background or be an adept musician themselves.

So I feel the purpose of my criticism is to say is this well executed? How will it affect you personally? How did it affect me personally? How does it stand in the field?

Geoffrey:

More about the experience versus the technical elements.

Peyton:

Yeah.

Geoffrey:

Sometimes wine reviews can devolve into technical elements. Some tasting notes are just a bunch of flavour descriptors. You know: “I taste blackberry, black currants, and blueberries.” And that’s very individual and personal. But also not very helpful to anyone.

When you’re at home having a glass of wine, it’s not like you’re thinking, “Oh, wow. I love this blueberry flavour.” It’s more, “I like this wine. I don’t like this wine. It goes with what I’m eating. It doesn’t go with what I’m eating.”

Peyton:

There’s a common music criticism fallback, which is just saying, “This sounds like this familiar artist.” I hate that because you’re asking the listener to have the same music background as you, which they may not. If I don’t understand the musical reference that you’re making, then it’s just lost on me. At least most people know what a blueberry tastes like, but if I say, “Oh, this album sounds like 1980 Sarah Records or The Field Mice,” then you’re like, “Huh? What? Who?” The references can get very niche, and I don’t like that.

Geoffrey:

So how do you approach that then if you’re not referencing other artists, you’re not trying to be technical? How do you communicate the feeling of a new album?

Peyton:

Sometimes I’ll use examples. I’ll use poetry. I will use essays that express a general idea. I don’t review a lot of solely instrumental music, and if I do then I will talk more about the approach of the recording than I would in an album where I have lyrics to analyze. Really, I’m almost a lyric critic. Because I’m also a writer myself; I write books.

So usually my approach tends to be more literary, and I’ll talk about wordplay and the delivery of a line. If an inference is significant enough, then I will mention it, but I’ll also try to place it in context so you’re not just scrambling in the dark if you’ve never heard of the band before. I try to put it in human terms that you can understand, whether you have the same music background as me

Geoffrey:

Then about scores, how do you approach coming up with a final score and how does that work?

Peyton:

I mean, I don’t get to pick the score. I don’t know if I’m letting out an industry secret here. I write the review, and I suggest a score range, but the score is up to the discretion of my editors and Pitchfork’s editorial team. I can’t unilaterally award an album Best New Music. I can advocate for an album when I think it deserves it, but that is not a guarantee that it will get the score I want.

Sometimes the score is quite a bit lower than what I’d like. Sometimes the score is quite a bit higher than what I’d recommend, But that’s pretty rare. Usually, I’m in agreement.

Something that is unique about Pitchfork is that it’s very rare for any album to get a perfect score or even a nine. People get mad about the scoring, but really anything over a seven is outstanding by Pitchfork’s metrics.

There’s one interesting example I can give, which is when I reviewed an album by an artist formerly known as Marina and the Diamonds. She just changed her name to Marina. I am a big fan of her past work, and this was a difficult one because the album just really was not very good. I think we wound up giving it a 5.5.

I took pains in my review to say, “This is a very talented artist who has a great body of work that I really believe in. And this really plays into some of the music industry’s worst impulses. It’s very generic.” But I think I made my argument very well. I got some great editorial guidance on it.

When the review dropped, I was terrified because this is an artist with a lot of very passionate die-hard fans. And there have been instances where my colleagues at Pitchfork, especially my female colleagues, have gotten death threats and endless harassment for giving Taylor Swift a 7.8, saying, “That’s not enough.”

So, when my 5.5 review came out, I was looking at the fan reaction, and all of her English-speaking fans were essentially in agreement with me. They were like, “Yeah, this is fair. This album really missed the mark. I love her, but this isn’t doing it for me.”

She also has a large Brazilian fan base. The Portuguese comments were just furious about the 5.5 and kept sending me memes of stuffed animals on fire and knives and furious Portuguese. Like “How dare you hurt Marina like this?”

There was a language barrier, so they couldn’t actually read the review. They were just furious over the score. Whereas people who could read the review were like, “yeah, that’s fair.”

Geoffrey:

I think when it comes to wine, there are a couple of challenges. The first is, even though wine reviews typically use a 100-point scale, in actual fact, they use a very small range of that scale. Most reviews really fall between 85 to 95 points.

A lot of critics will say, “It’s not about the score; it’s about the tasting note.” But that’s essentially a lie, because to consumers it’s all about the score. The score is what’s on the sticker on the bottle, it’s what’s going to sell the wine. If you don’t have a 90+ point score, you’re going to be in some trouble. Whereas getting that 90+ or 95+ score helps you sell some wine. There are a lot of wines I quite like and rate 88 or 89 points. Those are good scores in my mind. But to a winery or retailer they’re unusable.

Is there that same obsession with scores when it comes to music reviews? Or do you find that people are more balanced and say “Okay, here’s the score. But I’m going to read the review and consider that at the same time”?

Peyton:

There definitely are people who only look at the score and just get mad at the score and do not read the review. I think maybe the biggest recent example would be Taylor Swift’s Folklore album, which Pitchfork awarded an 8.0. Which is pretty rare. There are maybe 100 albums a year that will get an 8.0 or higher from Pitchfork.

And the review was glowing. There were a couple lines of critique about certain songs that the reviewer felt were lackluster, but it was a very positive review. The review goes up at 1AM and the reviewer’s phone started ringing in the middle of the night. She had to lock down her Twitter account because the hate was just dreadful. People were posting unflattering photos of her. It was very ugly. And it was because of the 8.0 score, it dragged down Taylor’s metacritic score. So, she had the best reviewed album of the year and, then after the Pitchfork review, she was only the fifth best album of the year.

So, the score certainly does matter. I also think scores tend to be inflated at other publications, whereas high scores are rarer at Pitchfork It means that when Fiona Apple gets a 10 out of 10, that feels historic. It really feels that is earned and deserved and special. So, I like the approach for that reason. I think we could maybe stand to be a little more sparing with eights and nines, but it’s not up to me.

Geoffrey:

Do you think regular Pitchfork readers understand and appreciate the significance of an 8.0 or 9.0 score?

Peyton:

For sure. I began reading Pitchfork in high school because the cool older classmate in my debate team was a reader and I wanted to be cool like her. So, it gave me a look into music that I wouldn’t have otherwise been exposed to. It asked me to be a little more discerning at a time when I was pretty enthusiastically listening to Hannah Montana, not that there’s anything wrong with that.

As Pitchfork has evolved, it’s become less white, less male. The reviews are more inclined to go global. And we’re reviewing things in different languages other than English. So, I think it’s become much more diversified and really opened up the idea of what a good album can be. Even along with that, they’ll now review pop. The Pitchfork of my high school years would never have reviewed Taylor Swift and now of course they would never not.

Geoffrey:

I guess it was several years ago that Pitchfork was criticized for its heavy indie rock bias. Presumably, and you can correct me if I’m wrong, a lot of their reader base had that same kind of bias. So, how do you overcome that and realize we need to branch out and be more inclusive of other genres? And are you expanding your reader base as you do that or are you changing the viewpoint of your existing reader base?

Peyton:

I think a lot of the shift happened because of social media and people becoming more vocal about the lack of representation of female artists, the lack of representation of artists of color. And it was a cultural shift that was much bigger than Pitchfork.

The Pitchfork that I grew up with was predominantly white male and indie, and catered to that audience. Now it’s diversified both the artists reviewed and the readership as well. It’s a Conde Nast publication now. So, it is mainstream. They do review a lot of standard pop albums, but it’s also one of the only music publications of its size led by a woman of color.

As a trans person, I feel able to bring that perspective to my work without any fear. And that’s very nice. And I think that it’s much more reflective of what music looks like today.

The impression I get from speaking to younger readers of Pitchfork is that it’s predominantly a youth urban music site. And that it caters more towards pop, R&B and rap. So, it’s interesting how much the public face has changed.

Pitchfork obviously still reviews plenty of indie. No one’s going hungry on the indie rock. I don’t know if there’s an analogy for that in the wine industry. I’ve read about natural wine.

Geoffrey:

Natural wine is probably the best equivalent. It’s almost a dogmatic approach where critics only review and drink natural wine, and anything that’s not natural is lesser than.

Which I think is unfortunate for so many different reasons. Again, I don’t think the average consumer really cares. I don’t know if this analogy will hold, but I’ll try it anyways. If you’re a fan of music, you probably don’t care what mixing console was used for an album. You care that it sounds good. Similarly, I don’t care what the winemaker did in the winery. If the wine tastes good, I’m thrilled. And if it doesn’t, even if it’s natural, I’m not happy.

Peyton:

Sure. Yeah.

Geoffrey:

Pitchfork’s known for making certain bands – rightly or wrongly. Arcade Fire is the classic example. When you’re deciding on a point score, is that something that’s at the back of your mind?

Peyton:

I think a Pitchfork score is less influential now than it would have been 10 years ago. There was a lot of discussion about that when Taylor Swift’s got an eight and Taylor Swift fans were furious. Long-time Pitchfork readers were like, “What are you talking about? That would have fed a man for five years.” And, it’s also clear Pitchfork no longer really has the power to end an artist’s career decisively with a bad review.

I don’t like to pan artists, and if I do have to do it, I try to be very thoughtful and really justify why I am giving the score and the criticism that I’m giving.

Usually I’m reviewing artists for whom this is their bread and butter or not even their primary job. So, I don’t want to be too harsh. I think there is maybe a subliminal understanding among music listeners that whether an artist is good is dependent on whether or not they’re in Pitchfork’s good favor. But that’s such a niche understanding even then. There are so many bands that tour and make money and have a devoted following, but that Pitchfork doesn’t review.

Geoffrey:

The most obvious comparison to me when it comes to wine reviewing would be a 100-point score. Which don’t come around very often, but when they do, they can catapult the wine to success. So you have critics who say, “I’m never giving a 100-point score. I think the idea of a perfect wine is ridiculous.” And then there are critics who are pretty generous in terms of how they give out 100 point scores.

But I don’t know how a critic doesn’t think about the life changing implications of giving a 100-point score, versus even a 99- or 98-point score.

Peyton:

I hear about that in restaurant criticism and food criticism. I’ve heard of glowing reviews shutting a restaurant down because they just can’t cope with the influx of new business. But unless it’s an especially outstanding score or best new music or a real pan, it’s unlikely to move the needle that much.

Geoffrey:

How do you see music reviews, or music writing more generally, changing and evolving over the next handful of years?

Peyton:

I think one interesting development, and one that I’m not a fan of, is the fact that Pitchfork’s biggest competitor at this point isn’t another publication. It’s Anthony Fantano. He runs a YouTube channel called The Needle Drop, and does dozens of music reviews a week. And he is massively influential. Pitchfork, has a large, diverse writing and editorial staff. But this is one white guy’s opinion. And it bothers me to think that we may be going back to the age of one white guy’s opinion.

There are also new systems being built up to allow fans to develop music criticisms on their own, without critical input. On forums like Indieheads on Reddit, there’s a consensus that builds among fans about what is good and what is not. And they will hold their own vote for the best albums and songs of the year. I think it’s becoming more democratic. And sometimes that means that one voice rises to an outside influence. And sometimes it means that you get this kind of grassroots consensus building, which is an interesting thing to see.

Geoffrey:

Wine previously had that dominant voice in Robert Parker. But he’s retired now, and no one has filled that void in terms of being able to drastically influence wine trends and sales.

Some people say we’re in the golden age of wine writing because there are so many different voices, so many great writers and perspectives. One of the things that’s interesting about wine is, because critics can review thousands of wines, you can latch onto one person and follow their reviews to guide purchase decisions. And it’s not because you don’t trust other people. It’s more, “I trust this person’s palate and what they like aligns with what I like.”

Peyton:

Especially for me; I will review at most one or two albums a month for Pitchfork. It is not my full-time job. It’s a different approach at the end of the year when I do have to take the whole years music into account and I’ll listen to a lot in a very short period of time. But usually my listening is very, very narrow and, I can really focus on what I’m reviewing.

Geoffrey:

What else do you work on outside of the reviews for Pitchfork?

Peyton:

I have a book coming out later this year. It’s called Both Sides Now, no relation to the Joni Mitchell song. It’s about a high school debater who is trans and goes to National Debating Championships only to learn that the topic is trans rights. And, he’ll have to argue against it if he wants to take home the gold. So, that’s what I’ve been working on. That’s coming out this summer. I do a little bit of writing for other outlets. But really the book is where my heart and soul is right now.