Canada’s Okanagan and Similkameen Valleys: an overview

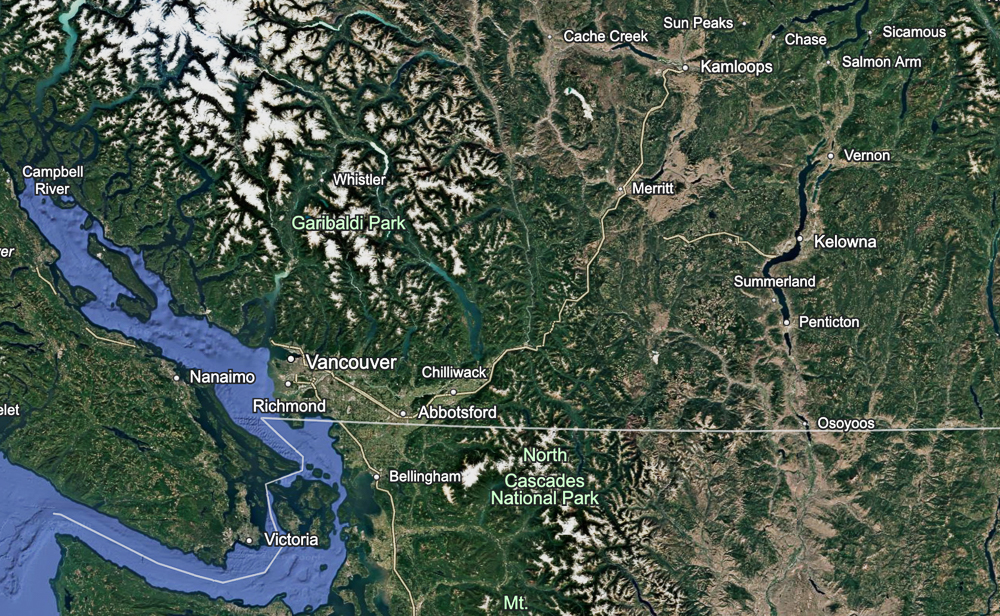

The Okanagan is quite spectacular. It’s the largest by far of the wine regions in Canada’s British Columbia, located some 400 km inland from Vancouver (about a four and a half hour drive, or a quick flight), and abutting the US border at its southern end.

The region is named after Lake Okanagan, a long, thin lake running north to south. It’s 130 km long, and averaging 3.5 km wide. It’s also quite deep (the deepest bit is 232 m), and it’s not uncommon to reach depths of 100 m just a few metres out from shore. Technically, it’s a fjord lake, carved out by repeated glaciations.

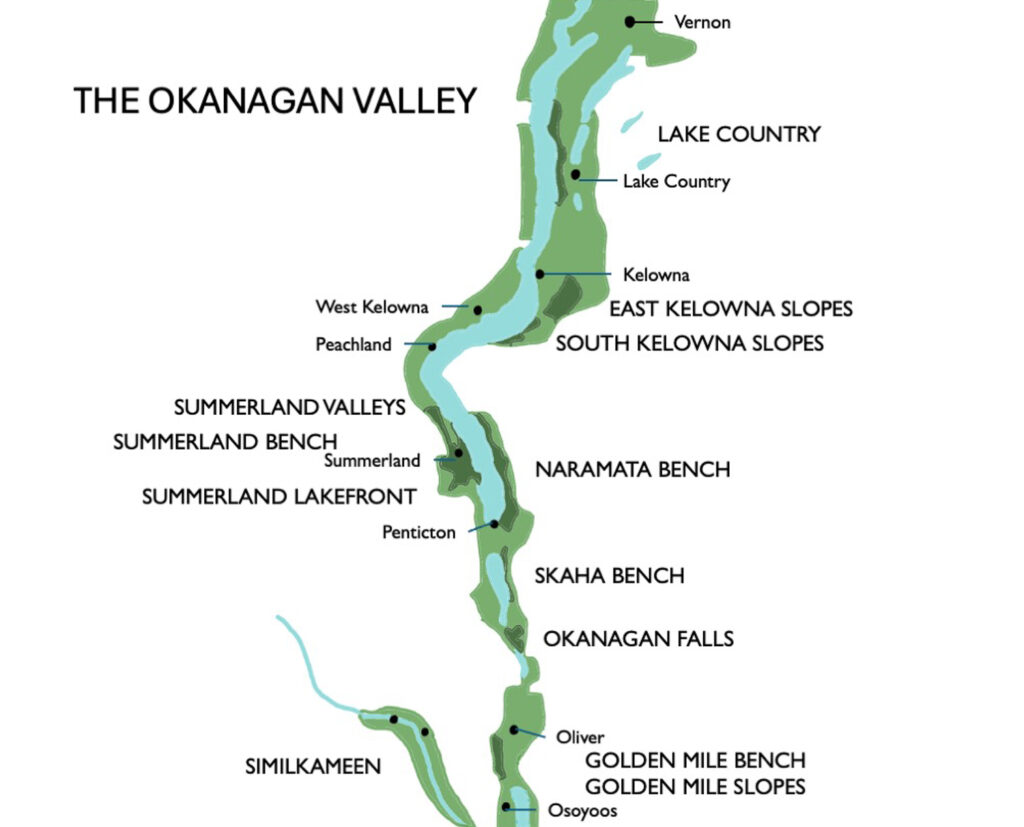

As for the wine region, this runs north to south and extends beyond the southern end of Lake Okanagan all the way to the border with the USA. Of all the wine regions I’ve visited, I can’t think of many with such a wide climatic range. In the northernmost part, Lake Country, it’s distinctly cool climate, suitable for Pinot Noir, Pinot Gris and Riesling. In the south, in Osoyoos, here we have rattlesnakes and sage brush (it’s the northen part of the Sonoran desert that runs down through the USA to Mexico), and you can ripen Cabernet Sauvignon and Syrah. In terms of growing degree days (GDDs), the Kelowna Slopes in the north run at 1200, then Naramata Bench in the middle is 1320, Golden Mile Bench near Oliver in the south hits 1480, and then Osoyoos abutting the US border is 1490. This is quite a range. For reference, Burgundy would sit somewhere around 1300.

One of the reasons the Okanagan has emerged as a successful wine region is because of the rain shadow effect of the coastal mountains. This means annual precipitation is just 318 mm in Osoyoos and 415 mm in Kelowna. This makes irrigation essential for growing wine grapes, although there are some tiny attempts to dry grow certain plots. The low growing season rainfall reduces disease pressure, and downy mildew is very rare here. Aside from winter cold, powdery mildew is the main viticultural challenge, along with leaf hoppers, which are sap sucking insects that can cause problems in some places, especially in warmer seasons where they get an extra life cycle in.

The latitude here: 49 degrees N at the US border, heading up to 50 degrees N in Lake County means that in summer the days are long. While we think of Canada in general as cool climate, the Okanagan is more short, warm climate. The winters are freezing, of course, but when things warm up in the spring and the buds burst, usually in early May, it gets hot fast. The vines motor ahead. Typically, a hot summer’s day here will reach 40 C, and then at night it will be distinctly cool, at 10 C. This diurnal range helps preserve acidity. There’s also a lot of sunshine. Frost returns in mid-to-late October.

In terms of grape varieties, Merlot and Pinot Gris are the most widely planted, but very few would call these the star grapes of the Okanagan. They are the backbone of many of the more commercial wine offerings that are so important for satisfying the thirsts of the many tourists here. The star grapes? Pinot Noir in the cooler areas is doing really well. Riesling is also a solid and sometimes exciting performer. Chardonnay does well throughout the valley. Cabernet Franc and Cabernet Sauvignon excel down in the south, where many of the best wines are Bordeaux blends. Watch out for Gamay, which can be exciting, and Syrah, which some tout as making the valley’s best red wines, particularly in the more southern vineyards.

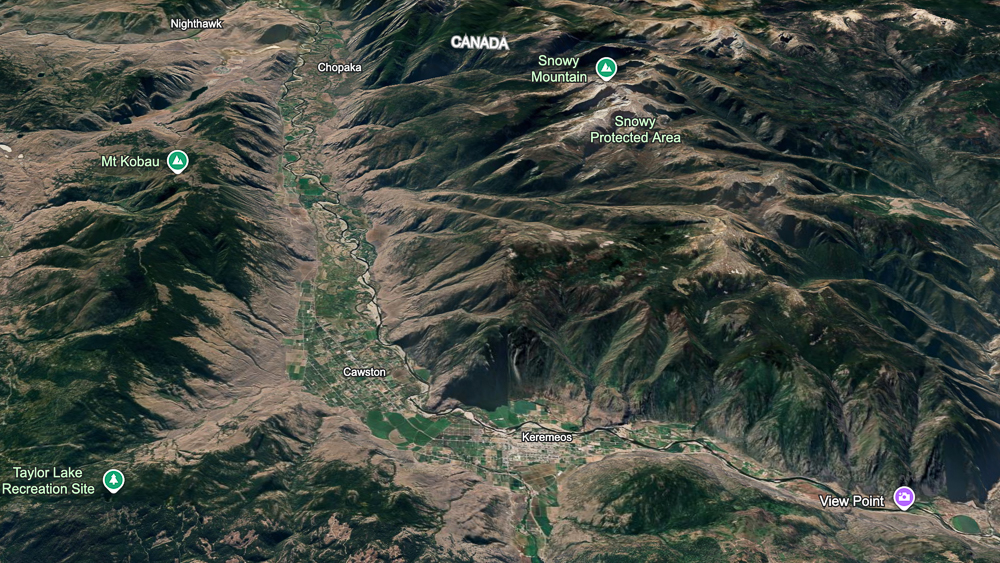

The Similkameen Valley is a side valley of the Okanagan, following the course of the Similkameen River. It’s dry and warm, but the ridges defining the valley are higher than in the Okanagan. Scenically beautiful, it is producing some exciting wines.

Extreme cold in the winter has recently emerged as a major issue. A cold snap in December 2022 damaged many buds on the dormant vines and reduced yields by 40% in the 2023 vintage, one that was also hit badly by smoke taint from wildfires (this is a common issue in the Okanagan). Temperatures were as low as -22.7 C in Summerland, and stayed below -18 C for 42 hours.

But this turned out to be just a rehearsal for the following season. Between January 11 and 15 2024, a cold snap hit the Okanagan Valley, where temperatures went as low as -28 C for three days. At Summerland, they got down to -26 C and stayed below -18 C for 57 hours. In addition, the rate of cooling was faster than in the previous winter’s cold spell. Lake Country got down to -28 C, Kelowna -27 C and Penticton also hit -27 C. These temperatures are cold enough not only to wipe out primary buds, but also secondary buds, which means no crop at all. What’s worse, is that they also damage the xylem of the vine, and this damage is irreversible and can accumulate, meaning that repeated cold spells – even if they aren’t at vine-killing levels – can cause vine death.

What this meant was that very few grapes were picked in the Okanagan in the 2024 vintage. It also meant that growers were faced with vineyards that had experienced significant damage. The question for many was whether to replant, or to try to recover the vines, for example by growing up new trunks from the bottom. In the interim, many sourced grapes (or juice) from Washington State, the nearest US wine region. Washington is a bigger region, and has a problem with over-production at the moment, so this worked well. Some high-end wineries specializing in Pinot Noir sourced grapes from the Willamette Valley of Oregon. This stop-gap solution worked quite well, and is being repeated for the 2025 vintage as vineyards are either recovering or have been replanted and aren’t yet producing. The labelling clearly states that the source of the grapes isn’t the Okanagan or Similkameen (which was also affected). It also gives Okanagan/Similkameen winemakers a chance to work with other fruit, which is interesting for them.

Since temperature records were kept in the Okanagan at the Summerland Weather Station, which began collecting data in 2016, there have been quite a few cold snaps that have got below -23 C (which is where there is around 50% bud damage for vinifera grape vines, as well as xylem damage). Prior to 1969, there were many events: 1968, 1964, 1957, 1950, 1943 and 1935 all saw big freezes. Then there were none until 1990, and the period from 1990 until 2024 saw none either.

Some notes on terroir. The Okanagan and Similkameen Valleys are the result of a lot of glaciation activity, the most recent of which was 9000-11 000 years ago. These glaciers scoured the valleys, leaving the dramatic landscape that can be seen today. During the retreat of the ice, the terrain below 500 metres was buried by sediment from the retreating glaciers. Just south of Okanagan Falls, the valley walls narrow, with one side formed by a large gneiss rock called nʕaylintn (pronounced nye-lin-tin, this has been the name for what before 2015 was known as McIntyre Bluff). At this narrowing of the valley there was an wall of ice and debris that blocked the southwards flow of the meltwater. This raised the level of the water (forming glacial lake Penticton), and so slackwater deposits of sediment between the wall of the valleys and the melting ice formed a series of silty terraces known as benches, which are the basis of many of the vineyards today. When the ice dam burst, this released water that carried lots of glacial sediments to the south Okanagan, creating benches largely made of sandy soils. Along the length of the Okanagan there have also been alluvial fans from the many creeks leading into the lakes that also bring some diversity to the vineyard soils. So the soil types here are largely glacial till, with gravels and stones, plus sand and silt from sedimentary deposits, with some alluvial contributions mixed in. In general, the soils in the south are sandier than those in the north.

Overall, BC has some 12 700 acres of vines (5140 hectares), with 341 wineries. The Okanagan accounts for 86% of this area (10 920 acres/4419 hectares), with the Similkameen Valley a further 6% (768 acres/311 hectares ).

If we split this down further by subregion (these are not the official sub-Gis, which I’ll come to later), this is the area under vine:

- Oliver 4657 acres (1885 hectares)

- Osoyoos 1560 acres (631hectares)

- Penticton 1479 acres (599 hectares)

- Kelowna 962 acres (389 hectares)

- Similkameen 768 acres (311 hectares)

- Okanagan Falls 644 acres (261 hectares)

- Summerland/Peachland 594 acres (240 hectares)

- West Kelowna 564 acres (228 hectares)

- Lake Country 459 acres (186 hectares)

Back in 2015 the first sub-GI in the Okanagan was delineated. It was Golden Mile Bench. Subsequent sub-GIs were established in 2018, 2019, 2021 and 2022. Here’s the full list. They were done on a sensible basis (physical characteristics) rather than politics, which is refreshing.

- Lake Country

- East Kelowna Slopes

- South Kelowna Slopes

- Naramata Bench

- Okanagan Falls

- Skaha Bench

- Summerland Valleys

- Summerland Bench

- Summerland Lakefront

- Golden Mile Bench

- Golden Mile Slopes