At Staffelter Hof in the Mosel, Jan-Matthias Klein has taken a bet on resistant varieties, vitisforestry and natural wine, and it’s working out

As part of the Porto Protocol Living Vineyards tour 2025, I visited Staffelter Hof, a winery looking to produce a new version of organic viculture with greater sustainability credentials, using resistant varieties (PIWIs) and vitiforestry.

Staffelter Hof, a winery based in Kröv (in Germany’s Mosel region) is full of history. It has a claim to be the world’s oldest continually active winery, dating back to AD 862. And Jan-Matthias Klein’s family have been here for 300 years. They were stewards of the monastery that used to own the winery, then they bought the winery from the French government in 1805 when Napoleon secularized the monasteries.

But it took Klein a while to decide that wine was his career path. Even though all the history put some pressure on him, he wasn’t sure for a while that this was what he wanted to do. ‘When you grow up in the Mosel, everyone thinks that the winemaker is the most stupid of the children who takes over the business,’ joke Klein. ‘There isn’t a lot of perspective, and winegrowing here is a lot of labour often for not so much reward.’ But in the end he decided to give it a go, coming back in 2005 after some travels and then taking over the whole cellar in 2014. Along the journey he did internships in Australia, New Zealand and France, and this helped him understand how special the Mosel was.

He started converting to organic farming, and then began using biodynamic practices, trying to reduce spraying of copper and sulfur. In 2011 he converted to organics fully. It took a while to make the full shift: in the Mosel there are lots of small parcels and if the neighbours aren’t organic it makes it complicated. So the first stage was a consolidation of holdings into contiguous blocks so that organics became a possibility.

Klein makes two lines of wines in his winery, Staffelter Hof. The first is a more classical range, from organically grown grapes. And then there’s his natural wines: these have cartoon-like labels and are made without any sulfite additions. The split between the classics and the natural wines is around 50:50.

With the natural wines, Klein has been experimenting. One of the innovations was to include two Portuguese varieties in his vineyards that he felt had promise. ‘The Portugueiser was meant to be a climate change project from the beginning,’ he says. He’d met some Portuguese winemakers at a wine blogger’s conference in Ismir, Turkey, and then in 2013 he travelled to Portugal. ‘I was amazed by the quality of Portuguese wines,’ says Klein. ‘Before I thought it was hard to find white wines in southern Europe that were at least almost as good as Riesling! I fell in love with two varieties: Arinto and Fernão Pires, and decided to plant them here in the Mosel.’

‘My friend Pedro Marques sent the vines by mail and I planted them on slate soils.’ He says. ‘It was a daring project – I thought the Fernão Pires could work most years because it is an earlier ripening grape, but Arinto is the Riesling of Portugal, a late-ripening, high-acidity grape.’

The next stage in bravery was the establishment of the vineyard of the future in a site called Kröv Paradies. This began as a project where organics could be made more sustainable through the use of the new disease-resistant varieties, the catchily named PIWIs, vastly reducing the need for spraying. And this was made even more sustainable and future proof by the incorporation of trees into the vineyard – a vitiforestry project.

This new vineyard approach was made possible by a land reform in the community. There are a lot of abandoned vineyards where family wineries had stopped farming, either because they had no one to continue or there is no money in it. But these abandoned vineyards cause problems for growers still working. As a result, the authorities introduced land reform where you can buy or swap land with everyone in the area. So Klein was able to get a significant block of 6 hectares of abandoned land that was ideal for starting this project. It’s an amphitheatre-like block, and I first saw it in December 2019 before it had been planted. The next time I visited was in September 2024, and it had been completely transformed. Most recently, I visited in November 2025, where I was able to meet with Nicolas Haack, an agroforestry consultant who helped Klein bring this project together.

It wasn’t considered a perfect site in the past because it faces more east than south, but with climate change Klein says it is perfect. There is a patch of forest on top, too, and by adding trees and hedges Klein has been able to connect this forest with the vineyard by way of some corridors, to ramp up biodiversity.

Haack runs a consultancy called Triebwerk, and he and Klein first met because Haack was involved in a community supported agriculture project in the Mosel focusing on wine. They got talking and found a lot of common ground, even though Haack’s background is with animal husbandry. Haack began by finding out what the goals of the project were, and how these could be translated into reality. One of the main goals was to bring life into the vineyard by fostering biodiversity. The use of resistant varieties and the use of sheep for grazing are also ways of reducing machine work in the vineyard.

Klein had already been using disease-resistant varieties, so he knew what he was dealing with. There are currently 2.8 hectares of vines planted in the 6 hectare site. The idea is to plant more vines and also more trees. The corridors also take quite a bit of space: they are 3-4 m wide and 50 m long.

One of the motivations for turning was a way to make the vineyards more resilient for the future. Climate chaos has had quite an impact in recent years, and this will continue. The idea is that the trees produce more shade, that the insects and birds are predators for pests. The trees will be allowed to grow to their full height, with the exception of fruit trees that are pruned for production.

For example, one of the new problems they’ve come across is the Drosophila suzukii fly which can oviposit through the grape skin and cause sour rot. This relatively new pest had only been a problem with red grapes, but recently they’ve found it in white grapes too. It’s a big worry, and one way to combat it is by increasing biodiversity. To this end they’ve added bird and bat boxes to the vineyard. There’s clear evidence that the bats have been using the boxes, and the trees have helped here: bats need landscape features like trees to be able to bounce their echo locations off to help them to navigate.

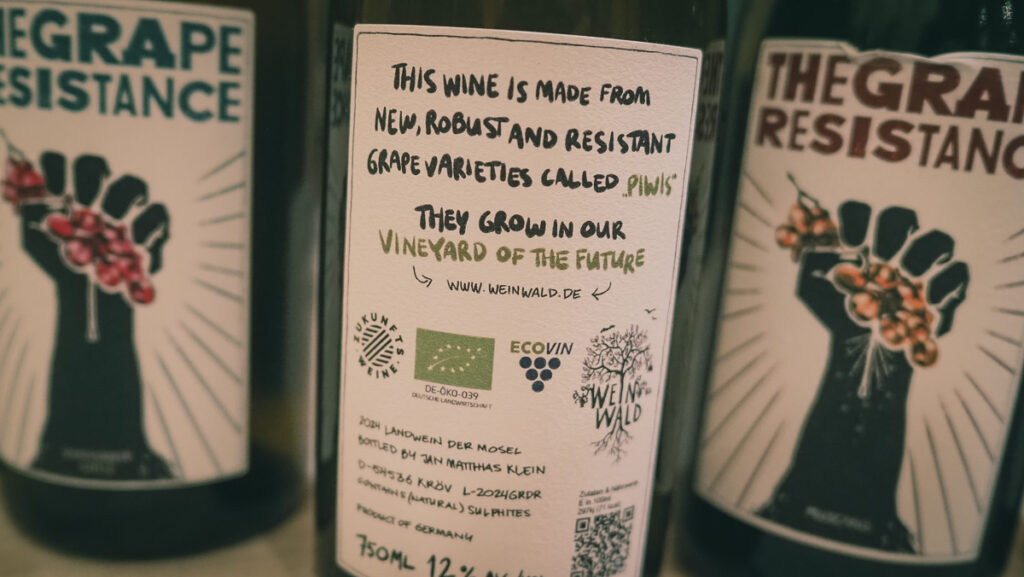

Klein began making natural wine in 2014, an initially the natural wines were made with vinifera varieties (including the Portuguese varieties Klein had imported), but there has been a shift to working with disease-resistant varieties. ‘After 2017/18/19 with the hot weather and problems with the climate I started investigating the PIWI wines,’ says Klein. He was alerted to their potential for making really good wine by one of his employees who’d worked at Niedermayr. ‘Since 2020 we have planted almost 4 hectares,’ he says, with much of this in the vitiforestry project. ‘It was quite a risk,’ he says. ‘If the wine had tasted shit we’d have made a big mistake.’ The first small vintage from the Paradies plantings was in 2022, and with the 2024 he’s launched a new label, Grape Resistance. These dramatically packaged wines carry a clear message on the back labels.

We take a walk to Paradies, and Haack describes the project’s evolution. ‘This was all fallow,’ he says, ‘and planting began in 2019. It with the Riesling on the top right, and that’s the only part of Vitis vinifera. The rest is hybrids.’ The later plantings are on a high trellis, because they would like to run sheep the whole year round.

‘From the get-go and the goal was to push the boundaries of what we know organic farming can do, trying to get a project going that’s as sustainable as possible,’ says Haack. ‘I think we’re quite close to these goals of bringing back biodiversity, and not just doing no damage, but actually doing something good. We want to go further than that and really develop a system that could also be translatable to other contexts or climates.’

‘We thought about what the problem parts are in viticulture. Here we have steep slopes, and everything’s expensive, with a lot of hand labour. It’s also physically demanding. And we want to reduce compaction because a lot of the work that we do here is with a Caterpillar system, which is quite intense, especially for spraying. And we also never really do it at the right time, if we’re honest. It’s often too wet to go into the vineyard to spray so there’s more compaction.’

The resistant varieties (PIWIs) are a big part of this project, because they vastly reduce the need for spraying. And the sprays, even with even for organic farming, are not great for insects and birds. ‘The PIWIs are an essential part of that because just genetically they will reduce the amount of spraying that was needed.’ It’s not going to zero, though, because there’s a need for one or two sprays to stop the fungi adapting to the genetics of the plants. ‘We have a responsibility for other growers to do this even though it might not be needed because of the disease pressure.’

They’d like to do these sprays with a drone, which avoids compaction. ‘The new technology that’s out there is quite precise, says Haack. ‘We’ve seen this from other growers in the area.’

‘The high-cordon trellis was inspired by Kelly’s [Mulville] work,’ he says. ‘We are starting to transform most of the varieties to a high trellis, but we won’t with Satin Noir because that kind of canopy won’t be great for [red wine] quality. We would get more pyrazines in the grapes.’

‘The other times we go into the vineyard is for mowing and suckering, and that’s why we are thinking of grazing. With the higher trellis, we can address that when we’re getting sheep into the vineyards.’

The Paradies vineyard has an old oak forest on top of it, so one of the goals of the project has been to create wildlife corridors that connect the vineyard to this biodiversity hotspot. ‘In the landscape we have here, the habitats are not connected to each other,’ says Haack. ‘Having corridors like hedgerows or trees is like a stepping stone for the insects and birds.’

‘The problem with the vineyard for the bats is that they can’t navigate in the vineyard. They need structures that are bigger to be able to fly around in the vineyards and to navigate through them.’

Klein explained some other plans for the site. ‘We want to create a picnic spot with information boards about the project, where people can just hang out when they’ve been hiking around and learn about the project,’ he says. He’s also got a vision for re-naturalizing a creek that is currently running underground in a pipe, at the bottom of the vineyard. ‘If we could open the creek and maybe make even a little pond here, and then plant some trees around it, with all the varieties which we use here in one spot,’ says Klein, ‘it would be an area where people can learn about the project playfully, and we could even create a special hike through the vineyards to further explain what’s happening here.’

‘We’ve not only made this because we want to work more sustainably and to get biodiversity here and then to make a more efficient way of organic farming, but also we want to inspire people to do the same,’ says Klein. ‘We want to bring people here to see it, learn about it and talk about it and spread the ideas.’

The vitiforestry side of the project is very interesting. We stand at the top of the slope looking down a row that has two trees planted in it. ‘In every row where you can see a tree up here, there’s also a tree further down,’ says Haack. ‘They were planted at the same time in every seventh row.’ The idea is for them to provide shade and habitats for birds as well as modifying the climate via transpiration, and also the fruit trees provide fruit that can be used to make ciders. These are planted at the top of the rows for practical reasons. ‘The idea is that the fruit trees are on the top where we can come here with a tractor and harvest from the tree,’ says Haack. ‘It’s just way easier.’

‘The difference between the shade of a tree and a brick wall is that the tree also transpires water, and that cools the area around it,’ he says. ‘So this is really what changes the microclimate.’ Haack explains that if we think of Riesling, we like the way it tastes now. With climate change, its taste will change, and vitiforestry with its climate-moderating influence can preserve Mosel Riesling the way we like it for the future.

While there don’t seem to be a huge number of trees in this vineyard, Haack says that there are enough for them to make a difference. ‘They are about 14 meters apart, and these are all strong, own-rooted trees. So they will produce quite a big, high-density crown.’ He adds, ‘but this is not going to be in 5 years, it is more like 15 years. And we have left a bit more space than I would normally do with other farms, because we’re here in a bit of a side valley, in a colder spot. In other places, I would probably go denser.’

I asked whether there would be mycorrhizal associations shared between the trees and the roots. ‘Yes, I believe so. But there are no really good studies on this, I’m afraid.’ They have reduced tillage and eventually will stop altogether so this will encourage more mycorrhizal associations.

THE WINES

Website: www.weinwald.de

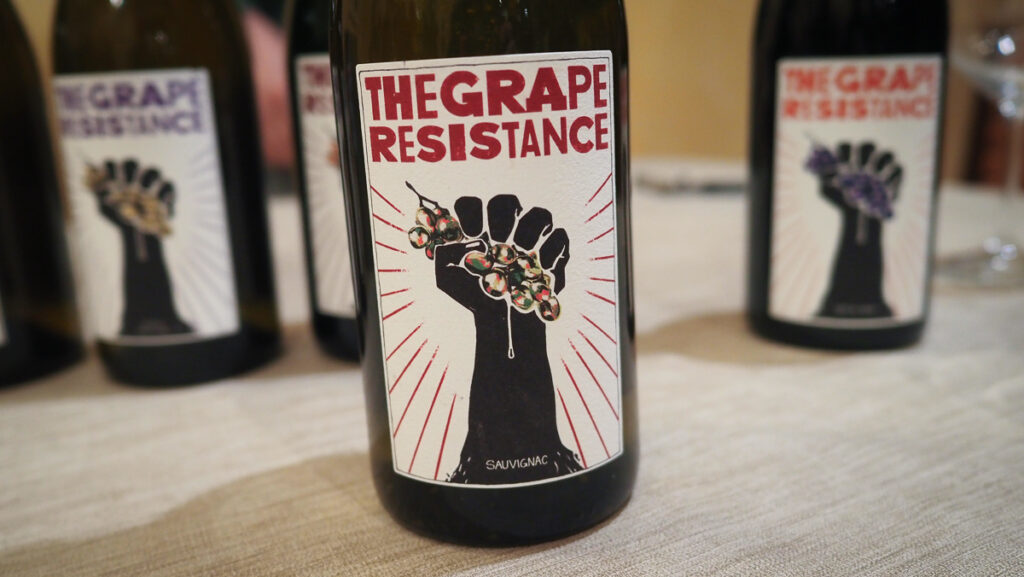

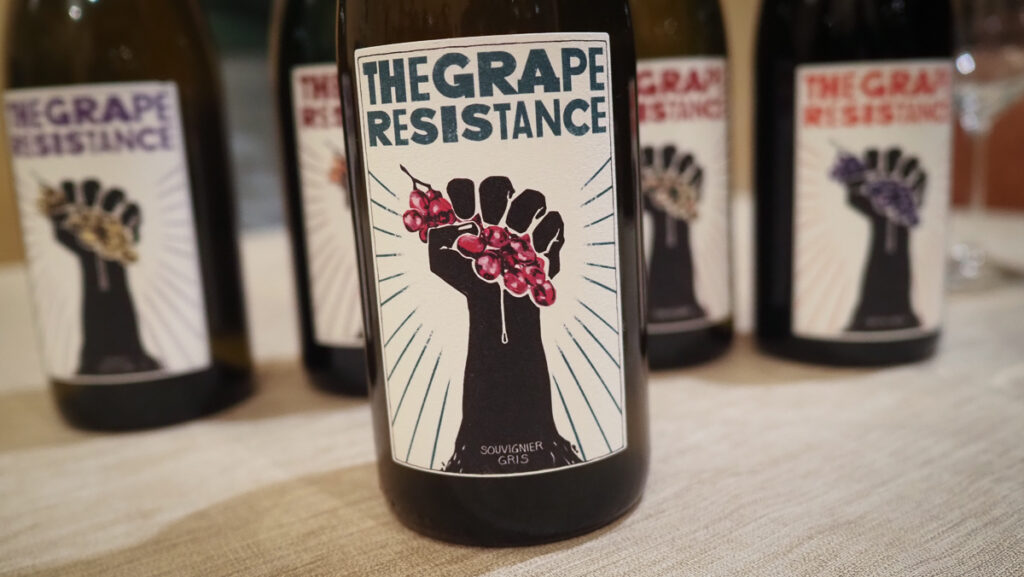

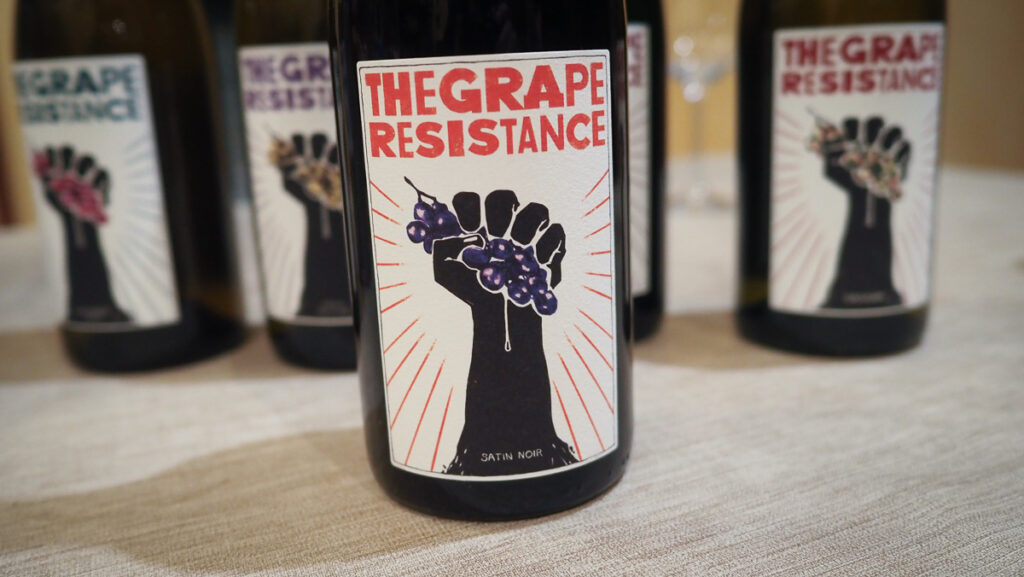

The Grape Resistance is the brand of wines that come from the vitiforestry project in Kröv Paradies. ‘We’d also like to grow this with the cooperative idea,’ says Jan-Matthias. The idea is that other people might want to plant PIWIs in a vitisforestry system.’ They also have some PIWIs that aren’t yet in vitisforestry which are used for the Staffelter-Hof natural wine range.

‘We don’t sell many natural wines to classic consumers, he says, ‘but the PIWIS we can sell more easily to them – maybe because they are more aromatic and clean.’

The first vintage from Paradies was a small one in 2022. The vintage were are tasting here, 2024 was tricky because of frost and hail (just 5000 bottles were made). ‘But 2025 was a very good vintage,’ says Klein, ‘and will produce a lot more, although some will go into the Staffelter-Hof range.’

Prices in Germany for these wines: €18 for PetNat, Donau Riesling and Souvignier Gris, €15 for Sauvignac, and the Satin Noir is €16.50. None have added sulfites.

I also went through the cellar trying the 2025s, early on in their life. These were an impressive set of wines, and show that Klein is on the right lines with this project.

The Grape Resistance Sauvignac 2024 Germany

11% alcohol. 3 hour skin maceration then pressed. Stainless steel, no added sulfites. Beautiful aromatics of honeyed floral citrus and pear fruit, with some grapey notes. The palate has a little fizziness but still bright and pure, with grapefruit, table grape and melon, with some herby hints. So bright and juicy. Lovely freshness here. Tasted a few hours later this had begun to develop a little mouse, so take care and drink soon after opening. 92/100

The Grape Resistance Muscaris Pet Nat 2024 Germany

11% alcohol. Muscaris is a cross of Solaris and Muskateller, and it has really strong aromatics. This has 10% Riesling in the blend to focus it a bit more. Undisgorged PetNat. They rack once or twice during fermentation and then bottle with 11 g/l sugar. Cloudy yellow. Lovely aromatics: grapey, floral, melon and a touch of citrus. Terpenic but balanced. The palate has lovely weight and concentration. It’s bold, grapey, melony and rich but then finishes bright and fresh with nice grip. Has a bit of bite on the finish. 92/100

The Grape Resistance Donauriesling 2024 Germany

12% alcohol. This grape is a little less resistant to powdery than other PIWIs, but the yield is good. This is vivid, bright and citrussy with nice grip and good acidity. There’s a touch of pear and melon here, but the core is bright lemony fruit. This did full malolactic: it was 12.5 g/l TA, and now it’s 8.1 g/l TA. Started off in stainless steel then finished in 500 litre barrels. Lovely precision and depth here. 93/100

The Grape Resistance Souvignier Gris 2024 Germany

12% alcohol. 7 months in used 500 litre oak. There’s a buttery note on the nose from malolactic, as well as cream and citrus. In the mouth it starts out very fruity, lemony and creamy, then finishes with high acidity. Lively and distinctive with real presence on the finish. This is distinctive and really appealing. 92/100

The Grape Resistance Satin Noir 2024 Germany

11.5% alcohol. Destemmed, 3 weeks maceration, then small oak (used). Had to pick a little early because of Drosophila suzukii coming. Fresh, perfumed blackberry and blackcurrant notes with a hint of green. Beautiful purity, good acidity and some freshness. Vivid and intense and so pure, with direct fruit. So delicious and quite intense, in a good way. 93/100