El Marco de Jerez: the terroir revolution in the Sherry Triangle, with Ramiro Ibáñez of Bodega Cota 45 (UBE, Agostado, Pandorga)

There is a revolution afoot in the Marco de Jerez (the Sherry Triangle that includes Jerez, El Puerto and Sanlúcar). One of the leading proponents is Ramiro Ibáñez, who is looking to make terroir-transparent wines from the top vineyards in Sanlúcar. Jamie Goode visits to see what’s going on.

It’s time to head off to Sanlucar de Barremeda to visit Ramiro Ibáñez of Bodega Cota 45. He’s one of the new generation in the Marco de Jerez (the Sherry Triangle) who are looking to recreate the great terroir-based wines of the past. One of his good friends, who he studied with, is Willy Perez, and they are collaborating in this quest, not only by making wines but also writing a book.

A video of the visit:

**

The history of the Sherry region has often been forgotten. In the past, it was very much vineyard based. With the emergence of Big Sherry in the 1970s, the vineyard area was increased and the emphasis shifted towards the large Bodegas. The wine became imprinted by the manufacturing process, not the place. Along with this shift, a new narrative around Palomino emerged: that it was simply a neutral variety, from which the sherry production process imprinted its own distinctive flavour.

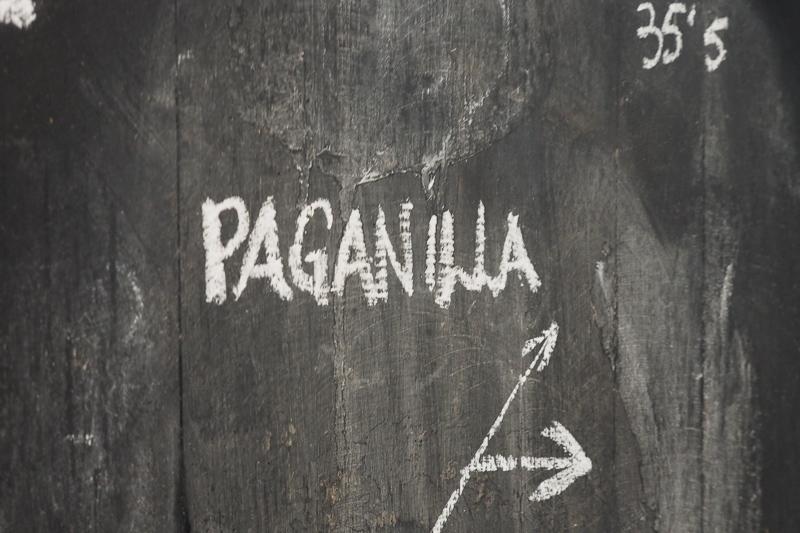

Ramiro explains that in Sanlucar, there used to be 100 pagos (designated single vineyard sites), but now there are just 60. He points out that within Sanlucar there is more variation over shorter distance than there is in Jerez. Travel a few kilometres and you go from vineyards that are Atlantic influenced, to those that are close to the Guadalquivir River. The latter vineyards are closer in character to those of Jerez. One pago – Balbaina – is shared between Sanlucar and Jerez. ‘The unique personality of Sanlucar is the coast,’ says Ramiro. ‘The fine, vertical wines of the coast are unique in Sanlucar.’

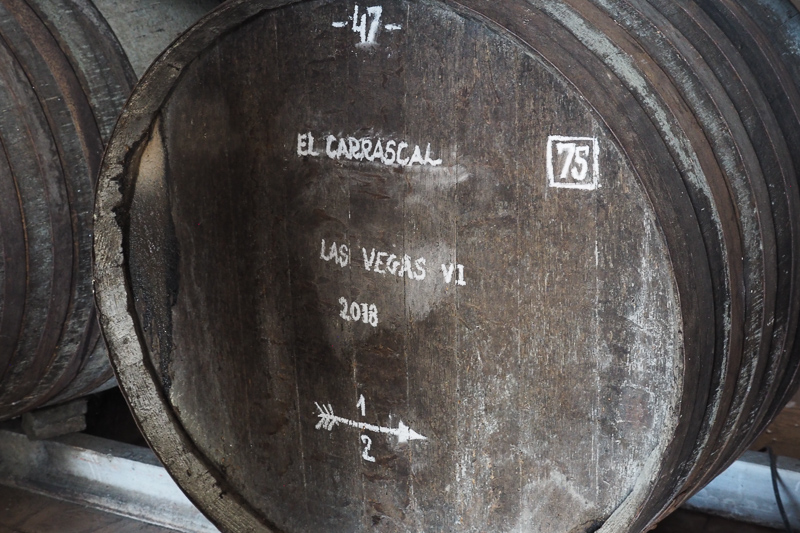

Palomino is the lens through which these terroirs are interpreted. Palomino is not neutral, he points out. It can actually translate the intricacies of the soils of the Sherry Triangle. There are 30 different clones, of which the most widely planted is the high-yielding Palomino California. One the back label of one of his wines, the UBE El Carrascal, he lists three different Palominos: Fino (73%), de Jerez (16%), and Peluson (11%).

The soils vary quite a bit here: previously they were underwater, and the deposits of albariza are from dead sea creatures, accumulating 1-5 mm per century. The nature of these fossils differs with the temperature of the water. They include plankton, phytoplankton, diatoms and formaniferas. This leads to a variety of different albarizas, which is another of the forgotten stories of El Marco.

This is quite a flat region, but altitude is a factor, as it determines what sort of soils were laid down by the seas in the past. The low lying areas, at sea level, have the least interesting soils. Things get interesting at 45 m, where you get a range of interesting albarizas. This is the reason for the name of the winery: Cota 45.

By the coast, the albariza is mainly Lenticuelas, which is soft-structured. The vines penetrate this more easily, and the grapes are generally bigger. Then 8 km inland, the albariza is more structured, harder to penetrate, with more stress for the vine, resulting in smaller grapes with thicker skins.

‘Albariza has clay, chalk and fossils,’ says Ramiro. ‘For me, the most interesting bit is fossils. There are 15-20 different types of albariza.’ He says that the fossils give elegance and sapidity.

Overall, the region – known as El Marco de Jerez – has 7000 hectares of vines. 4000 of these are in Jerez, with 1000 hectares in Sanluclar. This is a big change from the 1970s when El Marco has 23 000 hectares of vineyards, many planted in bad places. This was the era of Big Sherry. It was a commodity.

Ramiro grew up round here, but his family didn’t have a wine background. He says it wasn’t easy for him to work in the region, which is quite a closed world. There are just 66 wineries in the Sherry Triangle, and many of them don’t employ winemakers.

Initially, Ramiro studied agronomy, and then he studied winemaking in Porto Real. There were just 15 in the class, but one of them was Willy Perez. They became friends. In Spain, at the time you needed a first degree before you could study winemaking; this has since changed. He ended up working in a cooperative and at the age of 29 became the youngest principle winemaker in all the Sherry wineries.

30 years ago 50% of the bodegas owned vineyards. Now just 22 of the 66 have vineyard holdings.

‘We want people to understand that Sherry is more than modern day Sherry,’ he says. Back in the 15th century, Manzanilla was a small town in Huelva, and shipped wine to the Americas. It was a fresh dry white wine with a bit of flor. ‘In the last 30 or 40 years Sherry has just been selling a method,’ he says. ‘If it’s the method that’s so important, why not buy the grapes from La Mancha?’ He says that in the market today, very few Manzanillas come from single pagos. One example, he points out, is the the Juan Piñero Callejuelas, which is an old manzanilla in the style of the 19th century wines with 12-13 years of ageing. Another would be the Pastrana pago from La Gitana.

There is currently too much emphasis on flor. ‘Flor is very powerful,’ he says. ‘It’s not the most important actor, but after 1-2 years it takes more importance and is the biggest flavour for years 2-5. This is the period I like least: you just taste the method. After 5 years the yeasts decrease and the other flavours recover.’

Ramiro says, ‘the best period of Sherry was the end of the 18th Century and the beginning of the 19th. They had a lot of tools to work with and a knowledge of the vineyards.’

He also says that it is possible to taste the vineyard origins of the wines. ‘With each pago the geometry in the mouth is different.’ He recognises 50 year old sherries and finds similar flavour signatures to those from the same pago that are just a year old. ‘You can taste the pago.’

For example, with Maina there is an explosion on the back of the palate. With Macharnudo, it is in the middle of the palate: the figure in the mouth is more clean. For coastal pagos, there are little circles in the front of the mouth. With Miraflores, the geometry in the mouth always pushes to the front. ‘For me, the terroir is how the wine attacks the mouth.’

‘I want people to understand that sherry is more than modern day sherry,’ he says.

THE WINES

These were samples from cask, and are from different pagos.

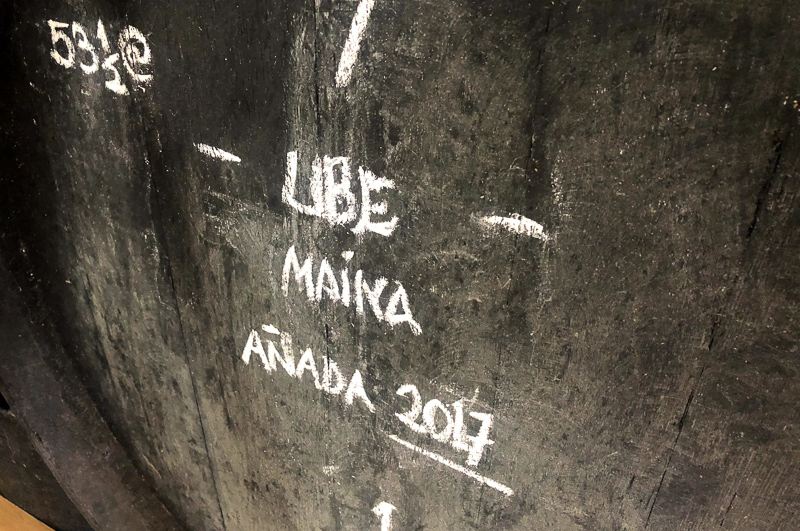

UBE Maina 2018

Astonishing nose: spicy and reductive with citrus and some petrol hints. Powerful palate is rich, tangy and spicy with lovely saline notes. Powerful, mineral and intense. 96/100

UBE Viña Las Vegas 2018

This is part of the Carrascal Pago, and it’s at 55 m altitude. The wine is a field blend of Palomino Fino, Palomino Jerez and Palomino Pelusón grown on Albarizas de Lentejuelas. It makes the UBE Carrascal. Intense, nutty and spicy with hints of caramel and raisin. The palate is supple and fresh with lovely citrus and pear fruit. Has warmth and texture but also a lovely mineral, saline streak. Such precision and an eternal length. 96/100

UBE Uva Rey 2018

This is a thick skinned, later ripening variety. It’s completely different and doesn’t usually have flor. Smoke and minerals on the nose with some petrol hints. Soft velvety texture with some pear fruit and also some roundness. Dense and lovely. 94/100

Bottled wines

Bodega Cota 45 UBE Miraflores 2016

12% alcohol This is the entry level wine and comes from five vineyards. 9 months in vat with flor. Tight and focused with citrus fruit and some spicy notes. This has real focus, a lovely minerality and some fine spiciness. Saline, vital and pure. 95/100

Bodega Cota 45 UBE Maina La Charanga 2016

14.5% alcohol. From Viña La Charanga in the Maina pago. Soils are Albarizas de Barajuelas, altitude 62 m. Fresh with a saline edge. This has lovely texture to the pear and apple fruit, with nice finesse and some richness. Such depth and focus with lovely texture. 95/100

Bodega Cota 45 UBE Carrascal Las Vegas 2016

73% Palomino Fino, 16% Palomino de Jerez, 11% Palomino Pelusón from Las Vegas. This is taut, saline, intense and so fresh. Spicy with a mineral core. Some hints of petrol and smoke. Primary, bracing and vivid with astonishing length. Has texture, and a salty finish. 95/100

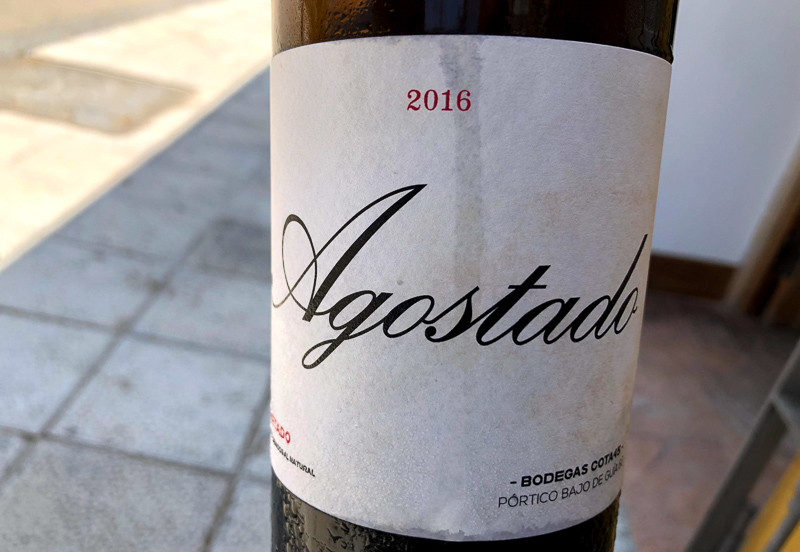

Bodega Cota 45 Agostado Cortado 2016

15% alcohol. This is an unfortified blend of 45% Uva Rey, 45% Perruño and 10% Palomino. Undergoes both biological and oxidative ageing. Oxidative, nutty and intense with a saline streak, some honey, nuts and spice, and showing great precision. Has a rounded texture. 95/100

Pandorga Pedro Ximenez 2017

8% alcohol. 10 days of drying of grapes in the sun, turned every two days. 327 g/l residual sugar. Powerful, sweet but balanced with raisins and spice, and some tea notes. Has table grape freshness. Very fruity, and despite the intense sweetness it has freshness. 94/100

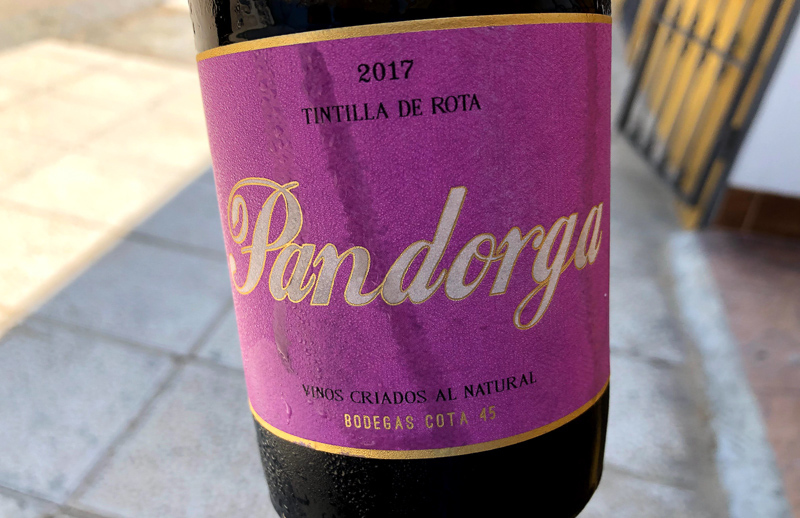

Pandorga Tintilla de Rota 2017

9.5 g/litre, 300 g/litre sugar. Dried 6 days in the sun. Sweet, raisined and very bright with table grape notes. Very rich but with some cherry hints too, alongside the raisin and grape characters. 93/100

UK agent: Les Caves de Pyrene

Find these wines with wine-searcher.com