The triune brain, and thinking of a triune wine tasting approach

In our heads, we have a remarkable organ. The brain. It’s mushy and jelly-like, and it weighs around 1.4 kilograms. As a kid I was fascinated by brains, but also quite repulsed by them, with all their ridges and folds. When we think about being human, there are two organs that stand out: the heart and the brain. They are widely used as metonyms for feeling and thinking. But it’s the brain where we think of ‘us’ residing. If you transplant someone else’s heart into your body, you are still you. But if you were to transplant someone’s brain into your head, who would you be?

The work of the brain is done by around 100 billion specialized information processing cells called neurons. It’s by far the most complicated organ in our bodies. These neurons are each capable of making an astonishing number of connections with other neurons, and it’s this interconnectivity that codes the very heart of what makes us ‘us’: our memories, personalities, emotions, hopes, fears and dreams are all dependent on the proper functioning of the brain. The neurons in the brain signal to each other electrically, and also through neurotransmitter and neuromodulator chemicals.

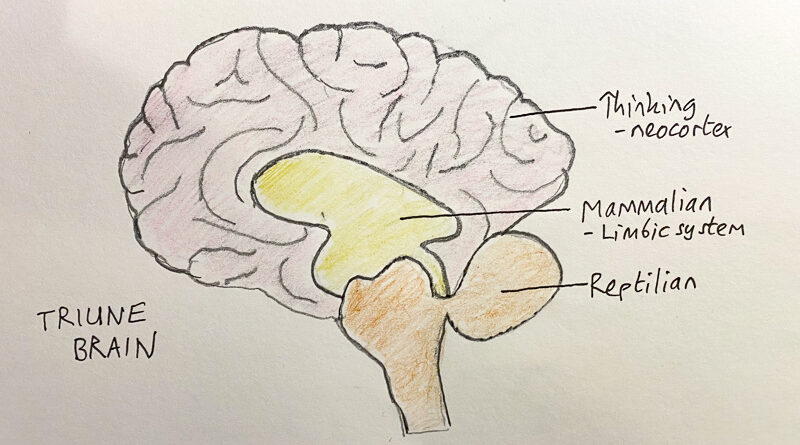

What about brain structure? It is complicated, and there are various schemes for classifying the different bits and what they do. Until recently, the most popular concept for how the brain works was the triune brain model devised by Paul MacLean in the 1960s. He took as his guide the way that the brain has developed through evolution, and divided up into three systems that have been bolted on to each other over time – as mammals developed from reptiles, and then as we humans finally showed up to the party, only fairly recently.

First there’s the ancient reptilian brain, which keeps our basic functions ticking over and is involved in sex, agression and appetite. At this level, we are selfish and instinctive. We got this bit of the brain from the dinasours. Think Jurassic park. This is the bit of the brain that can lead us badly astray – we need to tame it. When it runs amok, chaos ensues – but we need its drives, so we form an uneasy pact with it.

Then there’s the limbic system, which is known as the paleomammalian brain. This is the seat of emotions. This is the nice bit. We’re all loved up, empathic, touchy feely in this bit of the brain. Well, most of the time.

Finally, we have the neomammalian brain: the cortex, which is responsible for cognition, and which in MacLean’s model dominates the more primitive regions. This is where we have to operate from if we want to succeed; to be in control. If we allow the first two regions to take the lead, we will end up in a lot of bother.

MacLean’s model is immensely attractive as a simplification of how the brain might be functioning. But the hierarchical model is an allegory. It has been discredited by neuroscientists as too much of a simplification, but it remains popular outside the field – I’ve seen it taught by psychologists and counsellors.

Modern brain science contradicts the triune model, with its strictly linear, hierarchical manner of information transfer. While it might be convenient to divide the brain up and attribute certain functions to specific areas, there’s a lot of interconnectivity in the brain, with signals being sent one way and then back again, and multiple areas participating in the same tasks. Also, MacLean’s model places reason over emotion, and there’s every reason to believe that emotion is involved in decision making and shouldn’t be relegated like this.

But I still quite like the idea. Can we apply it to wine? Do we taste wine with different bits of our brain? This is an appealing idea.

First of all, our reptilian brain. Does wine trigger something here? I think our base instincts can be roused by the right wine. This is a visceral, raw way of appreciating it. Take a slug and just drink it. Feel its effect. Some wines touch this bit of us more than others. And then, of course, there’s the effect of the alcohol, liberating us – and perhaps lessening the control of the neocortex on the other two older regions.

Then our limbic systems. Wine can definitely be emotional. It can touch us in deep ways and move us. Again, the alcohol plays a role here. Memory is part of the limbic system, and this plays a big role in tasting wine. Smells communicate to us, and have the capacity to move the emotions and influence decisions even at levels where we are not consciously aware of them.

Finally, our neocortex. We think about what we are drinking, and interrogate the wine. What does it have to say? The intellectual appraisal of wine; the turning of perceptions into words so we can order them and make sense of what we are drinking.

I propose that even though the triune brain has been discarded by neuroscience, that we should keep the concept, and start doing triune tastings. Don’t rush to the thinking bit – the neocortex. Begin in the reptilian brain and engage deeply with the sensation of the flavour, without turning it into words. Dwell there a while, among your base instincts! Imagine you as a dinosaur. Roar a little if you have to.

Then the mammalian brain, the limbic system, can be engaged. We can dwell in the emotion prompted by the wine. This is a good place to be. Again, it requires resisting the urge to rush to words and thinking actively about the wine. Rather, we dwell in the experience and are sensitive to our bodies: where do we feel the experience of the wine? How do we enjoy it? How does it make us feel.

Then, we can jump to our neocortex, and bring all this together. Triune tasting.